Denise Taylor, bottom right, is interviewed by USC alumna Lynette Jenkins during the homeless count. (USC Photo/Gus Ruelas)

Latest count shows number of L.A.-area homeless up 23 percent in one year

USC researchers provide key analysis of the data gathered annually by the county and city, as part of the university’s Initiative to Eliminate Homelessness

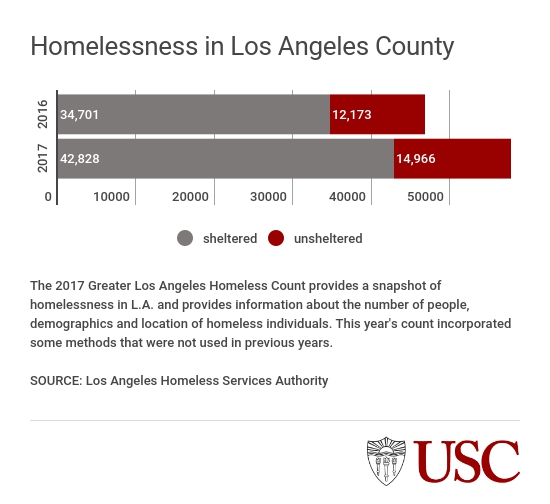

The number of homeless people in the Los Angeles area has increased 23 percent to 57,794 since the 2016 count, according to latest data analyzed by USC researchers for the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

The results of the latest homeless count were released Wednesday by LAHSA officials in coordination with elected officials, including Mayor Eric Garcetti and Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas.

“There is no sugarcoating this bad news: Our count is up,” Garcetti said.

The 2017 count marks the first time that USC researchers have taken on the task of analyzing the data gathered annually by the county and city to monitor the levels of the crisis. The annual data from the point-in-time survey submitted to the federal government are a reference for determining government funding and programs to address homelessness. This year marked the first time that USC was a partner with LAHSA on the count.

The 10-day count is conducted each year at the end of January and is a massive effort involving multiple agencies, including the City of Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, the Los Angeles Police Department, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, several cities and communities in the greater Los Angeles area, and neighborhood councils and coalitions.

For its part, USC provided expertise on data gathering and in-depth analysis. In addition, 350 volunteers from USC helped with the count.

“The new homelessness count shows significant increases in people who are living on the streets, in vehicles and encampments in Los Angeles County,” said USC Provost Michael Quick. “These data show the importance — and timeliness — of our work at USC to develop cross-disciplinary approaches to this growing epidemic and to work with all stakeholders.

“I look forward to seeing the results of these efforts. It is our responsibility as a leading research university to contribute to solutions that will end homelessness.”

‘Powerful working relationship’

Peter Lynn, LAHSA executive director, said the new partnership with USC is “an incredibly powerful working relationship” that enhanced this year’s results and contributed to what he said was an unprecedented volunteer turnout of 8,000.

It is our responsibility as a leading research university to contribute to solutions that will end homelessness.

Michael Quick

USC has made homelessness a priority issue for the university to help solve. A year ago, USC President C. L. Max Nikias announced a new collaboration between the university and partners in the public, private and nonprofit sectors to end homelessness in Los Angeles to serve as a model for other communities. In the fall, Quick also announced the formation of a steering committee focused on the elimination of homelessness — a “wicked problem” — as one of the university’s top priorities.

USC’s partnership with LAHSA builds upon the university’s collaborative effort to end homelessness in Los Angeles, as well as the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work’s leadership in a national effort by the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare, “Grand Challenge to End Homelessness.”

“USC is training tomorrow’s workforce to assist with homelessness and those affected by it,” said Brenda Wiewel, director of USC’s Initiative to Eliminate Homelessness. “Our faculty, researchers and students are busy using their expertise. They are developing innovations, high-tech solutions and community interventions that will directly impact and reduce the number of people who are homeless.”

With USC researchers’ input, LAHSA made some changes in how the data were gathered. For example, LAHSA asked fewer questions of young people who were homeless, reducing the number of questions from 45 to 39. The agency also updated its list of hot spots where young people can be found so that volunteers could target those areas for the youth survey to increase participation.

Other changes included a collaboration with Los Angeles County park rangers to help with the count, as well as conducting surveys at family resource centers. In addition, LAHSA also introduced “response cards” for volunteers to use when asking sensitive and highly personal healthy questions — such as whether someone has HIV/AIDS or has been a victim of domestic violence. Anyone homeless who did not want to give a verbal response could answer the question by pointing to an answer listed on the card.

City and county officials applauded LAHSA and USC for the changes in data gathering.

“Our numbers are more accurate,” Garcetti said.

Deep dive

A deeper dive into the 2017 count reveals that the most notable increases were among youth, particularly those 18 to 24 years old (up 64 percent at 5,645), reflecting increased participation. The number of homeless Latinos also rose 63 percent, to 19,391, and the number of homeless veterans increased 57 percent, to 4,828.

LAHSA reported that the proportion of people experiencing homelessness for the first time also has increased, from 57 percent in 2016 to 60 percent this year.

Substance abuse and mental illness are two common struggles frequently cited as factors in homelessness. The number of homeless adults 18 and older who struggle with abuse actually decreased by 11 percent to 9,285 people, but those with serious mental illness increased 13 percent, to 15,728.

In effect, those increases in mental illness and the decrease in substance abuse did not explain the 23 percent overall increase in homelessness.

Minorities are disproportionately impacted by this crisis, which doesn’t seem to be driven by mental illness or substance abuse.

Robynn Cox

“Minorities are disproportionately impacted by this crisis, which doesn’t seem to be driven by mental illness or substance abuse,” said Robynn Cox, an assistant professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work with and an economist who also works with the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. “This suggests that we need to do more to understand housing insecurity in general, so that we can understand how to prevent individuals and families from experiencing its most extreme form of homelessness.”

Where do many of the homeless in Los Angeles end up staying? The count shows 14,412 live in vehicles and encampments, a 26 percent increase from last year’s 11,472.

Elected officials noted that the increase in homelessness is occurring even as they have ramped up efforts to construct affordable housing and provide more temporary and permanent housing. LAHSA reported that 14,214 people were moved into permanent housing since the 2016 count.

“We knew full well and intuitively that there was an uptick” in homelessness, Ridley-Thomas said. “The good news is that we now have the capacity to for the first time to stand up to it.”

New resources

Ridley-Thomas was referring to recent measures passed by voters in the Los Angeles area that provide new funding for the city and county to address homelessness.

In March, county voters approved Measure H, a quarter-cent sales tax increase that is expected to generate $355 million annually for homeless assistance programs over 10 years. It was tandem to a separate measure, HHH, approved by city voters in November to start a $1.2 billion general obligation bond that would pay for the construction of affordable housing for homeless people in the city that would include spaces for supportive services, such as counseling.

“We know there are evidence-based solutions to address homelessness once it has happened, and recent measures should help scale up these best practices, yet the results of the count speak to a need to better understand ways to prevent homelessness and alleviate housing insecurity that is even more pervasive,” said Assistant Professor Benjamin Henwood of the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work who led the USC team on the count.

“The findings underscore the need to expand a trained workforce to help engage and respond to the needs of an increasingly large and diverse population of people who experience homelessness.”