Fish get arthritis, too

Scientists could use zebrafish to accelerate arthritis research.

Scientists could use zebrafish to accelerate arthritis research.

Contact: Zen Vuong at (213) 300-1381 or zvuong@usc.edu

The very first bony fish on Earth was susceptible to arthritis, according to a USC-led discovery that may fast-track therapeutic research in preventing or easing the nation’s most common cause of disability.

The finding contradicts the widely held belief that lubricated joints enabling mobility — called synovial joints — evolved as vertebrates ventured onto land. For example, human knees and hips have synovial joints, which are highly susceptible to osteoarthritis.

Pixar’s Dory, zebrafish and other ray-finned fish have synovial joints that can get creaky. Thus, these fish are susceptible to arthritis.

“Developing the first arthritis model in the zebrafish — an emerging regenerative model for medical research — opens up fundamentally new approaches toward finding a cure for arthritis,” said Gage Crump, senior author and an associate professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “While arthritis is the leading cause of disability in the United States, there are no treatments beyond artificial joint replacement. Our research offers new hope for finding a biological cure.”

Amjad Askary and Joanna Smeeton from Crump’s laboratory have found that certain joints in the zebrafish jaw and fins have features that resemble the synovial joints found in mammals. The similarity makes sense because water resistance places considerable strain on joints. The study will be published in the journal eLife on July 19.

Arthritis affects more than 52 million people or about 23 percent of adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Aging baby boomers will spike that number to 78 million — or about 26 percent of adults — by the year 2040.

How zebrafish are like us

Four-limbed bony vertebrates such as humans evolved from lobe-finned fish. However, a good laboratory model for this group does not exist, so instead the researchers focused their inquiry on zebrafish, a member of the more evolutionarily distant ray-finned fish.

Four-limbed bony vertebrates such as humans evolved from lobe-finned fish. However, a good laboratory model for this group does not exist, so instead the researchers focused their inquiry on zebrafish, a member of the more evolutionarily distant ray-finned fish.

Using CT scans and genetic tools, the scientists noted that two other ray-finned fish — the three-spined stickleback and the spotted gar — also have synovial joints that produce a protein very similar to what lubricates joints in humans. It is aptly named Lubricin.

Previous research showed that humans and mice lacking Lubricin have poor joint lubrication and develop early onset arthritis. Askary, Smeeton and their colleagues found that removing the Lubricin gene from the zebrafish genome causes the same early onset arthritis in their jaws and fins.

Given that fish and humans diverged hundreds of millions of years ago, when bony vertebrates first evolved, this similarity in arthritis susceptibility reveals that synovial joints are at least as ancient as bone itself.

“Creating the first genetic osteoarthritis model in a fish is exciting,” Crump said. “Going forward, it will be fascinating to explore whether the zebrafish, which is well known for its regenerative abilities, can also naturally repair its damaged joints.”

“Creating the first genetic osteoarthritis model in a fish is exciting,” Crump said. “Going forward, it will be fascinating to explore whether the zebrafish, which is well known for its regenerative abilities, can also naturally repair its damaged joints.”

Additional co-authors include Sandeep Paul and Simone Schindler from USC, Ingo Braasch from the University of Oregon and Michigan State University, John Postlethwait from the University of Oregon, and Nicholas A. Ellis and Craig T. Miller from the University of California, Berkeley.

Support came from a California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Training Fellowship and a Wright Foundation Award.

# # #

Top image: An adult zebrafish skeleton stained for bone (purple) and cartilage (blue). (USC/Gage Crump Lab)

Middle image: Magnification of the adult zebrafish jaw skeleton. The jaw joint (middle) functions as a lubricated hinge. (USC/Gage Crump Lab)

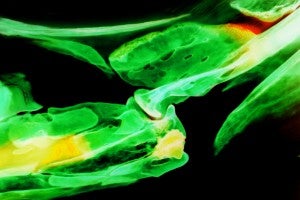

Bottom image: Cellular resolution image of the developing zebrafish jaw joint shows cartilage cells (red) beginning to acquire synovial characteristics (green). (USC/Gage Crump Lab)