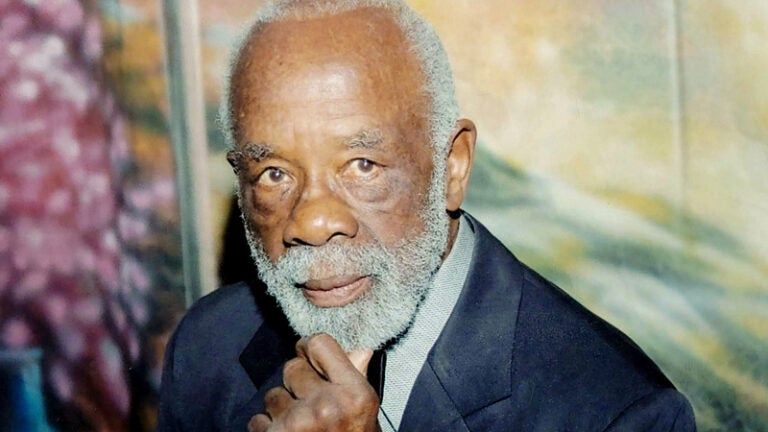

Ted Lumpkin was a member of the first all-Black flight squadron in the U.S. military. (Photo/Courtesy of the Lumpkin Family)

Remembering Trojan and Tuskegee Airman Ted Lumpkin

The USC alumnus served the country he loved as a member of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ first all-Black fighter squadron.

Theodore Lumpkin’s wife and children knew that he once had served in the U.S. Army and had been stationed overseas. But it wasn’t until decades later, when they happened to see Lumpkin and his military unit honored on a television show, that they discovered he had been a war hero. He was a man of the Greatest Generation, a believer in character and quiet resilience.

Theodore Lumpkin’s wife and children knew that he once had served in the U.S. Army and had been stationed overseas. But it wasn’t until decades later, when they happened to see Lumpkin and his military unit honored on a television show, that they discovered he had been a war hero. He was a man of the Greatest Generation, a believer in character and quiet resilience.

Lumpkin ’47, MSW ’53 — one of the last original Tuskegee Airmen — died of COVID-19 on Dec. 26, 2020, just a few days shy of his 101st birthday.

A native Angeleno, Lumpkin served as an Army intelligence officer during World War II. After the war, he used the GI Bill to enroll at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. After getting his master’s at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, he began a career as a social worker with Los Angeles County. Later in life, Lumpkin became a real estate agent.

He also traveled the world to raise awareness of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first all-Black flight squadron in the U.S. and a key unit cited in the desegregation of the military.

After his death, countless tributes and obituaries from throughout the country poured in, a testament to his lifelong dedication to service.

“I had no idea so many other people cared,” says his widow, Georgia Lumpkin. “It wasn’t like he was Martin Luther King or anything. I’m just amazed, and of course honored, but I’m just amazed, that’s all.”

Humble Origins

Georgia remembers meeting her future husband while he was still a student at USC in the 1940s. She worked at the Bureau of Public Assistance and Lumpkin would visit as a student. She recognized his unique last name because all of the county’s foster care paperwork went through her desk. Years prior, the Lumpkin family had taken in a foster child and Georgia recalls reading through the file.

Decades before you could look up a potential date on Facebook or Instagram, Georgia had a file with everything on the Lumpkin family. The file mentioned a son who had served in the military and came back from war living in a closet that was turned into a bedroom.

“On paper, they were a wonderful family, and everything I experienced lived up to that,” Georgia says.

People who met Lumpkin in recent years were surprised by how sharp a man born in 1919 was. He’d visit elementary schools throughout Los Angeles to talk about the Tuskegee Airmen and trekked across the country to attend meetings of squadron chapters and of organizations dedicated to the group’s legacy.

It was a good feeling to be judged by your ability and not by the color of your skin.

Ted Lumpkin

He also spoke at USC. During one of his last visits, shortly after his 100th birthday, Lumpkin recalled a story of his time in the war that underscored the impact the Tuskegee Airmen had on a segregated military.

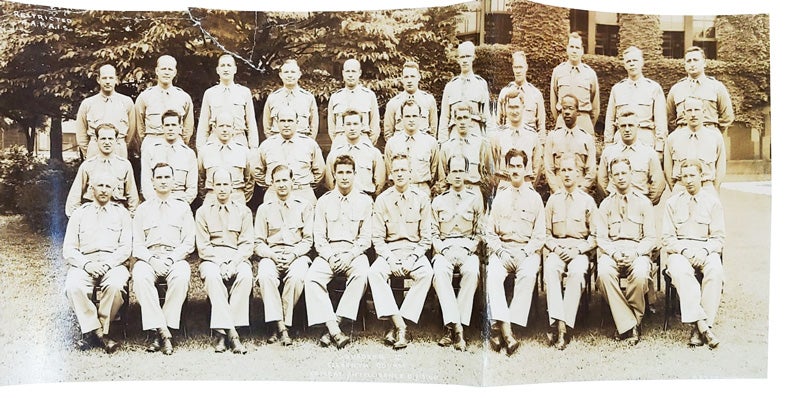

Lumpkin’s job was to brief and debrief fighter pilots tasked with escorting bomber planes to and from their targets in Europe. The all-Black fighter pilots and all-white bomber crews were stationed in separate bases and never saw each other face to face.

That is, until a severe storm grounded both groups in the same air station. Up until that point, the military men in the bomber planes had no idea that the fighter pilots they’d been trusting with their lives were Black. “They were shocked,” Lumpkin said of the moment when the white crew members found out.

The two groups spent several days sharing the base with no incident. There were no protests or tensions. “It was a good feeling to be judged by your ability and not by the color of your skin,” Lumpkin recalled in 2019.

Celebrating a Decades-Old Legacy

Like many World War II veterans, Lumpkin initially talked little about the war. His wife and children didn’t know about the Tuskegee Airmen, similar to how they remained unknown to most of America until much later.

His youngest son, Ted Lumpkin III, remembers learning about the Tuskegee Airmen in the early 1980s. He learned about it through a television show called That’s Incredible.

You just do your best, live your life and everyone is going to treat you based on your character and accomplishments. He zeroed in on the power of education and how that levels the playing field.

Ted Lumpkin III

Lumpkin III remembers announcers hyping up the program by telling the audience about a successful all-Black fighter squadron in World War II that had never been recognized for their bravery.

“I don’t think they called them the Tuskegee Airmen yet,” Lumpkin III recalls. “They said, ’This happened, this was incredible, you’ve probably never heard of these guys so we’re going to honor them now.’ Everyone was walking in, and there’s my dad on stage.”

Never one to boast, Lumpkin hadn’t told his family that he’d appear on television that night. Lumpkin never dwelled on the past and didn’t allow the evils of racism to sour his heart, his family says. Despite living through segregation and spending time in the Jim Crow South, Lumpkin rarely spoke about the discrimination of that era. Instead, he instilled into his children a profound respect for education.

“There was never any talk of persecution or anything along those lines,” Lumpkin III says. “You just do your best, live your life and everyone is going to treat you based on your character and accomplishments. He zeroed in on the power of education and how that levels the playing field.”

Lessons for a New Generation

One particular moment illustrates Lumpkin’s ability to rise above hate.

In 1973, Lumpkin took his youngest son to hear Mayor Tom Bradley speak in what would have been the equivalent of his inauguration. Bradley was the first — and so far, only — Black mayor of Los Angeles.

“I’ll never forget this. There was a group of guys across the street from the event dressed in Nazi uniforms,” Lumpkin III says. “My dad obviously fought in World War II against these guys, against their view of the world. He just passed them and said, ‘Yeah, some people feel a different way, but freedom of speech is important. We’re here to listen to Tom Bradley.’”

He was particularly proud of his work with the Tuskegee Airmen Scholarship Foundation and donated thousands of dollars to the charity each year, according to the foundation’s former president, Jerry Hodges ’50. Hodges and Lumpkin often traveled to events together. Both were USC alumni and original Airmen. They also shared a pride in their education.

“One of the things I was proud of was that I took every course in accounting that USC offered at the time,” Hodges says. “I was trying to get all I could before I got out and started hustling in the community.”

The two often returned to their alma mater to share stories about their time as Tuskegee Airmen.

Jennifer Chung-Vanzani, the director of advancement at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, remembers Lumpkin driving to campus in his Toyota Prius and staying late to talk with anyone who had questions for him. Amazed by how active he was, she’d often ask him for his secret.

“He always said, ‘I have a great wife,’” Chung-Vanzani says.

Lumpkin leaves behind his wife, four children, nine grandchildren and one great-grandchild.