With mixed emotions, three generations of one Trojan family close a chapter in history?

Niki Kawakami will be the fifth in her family to earn an advanced USC degree — but her grandfather was cheated of his during World War II. Eighty years later, a gap in justice is closing.

When Niki Kawakami walks in USC’s commencement May 13, her mother and uncle will be there. Both earned USC degrees in dentistry in the 1980s.

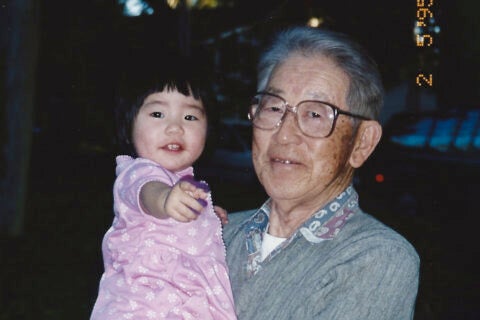

But Niki’s maternal grandfather, Tadashi “Tad” Ochiai, will be missing.

This hard-core Trojan fan who sent his son and daughter to USC died in 2012 at the age of 97 without completing a degree from USC.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. It forced Japanese Americans of all ages into detention centers across the West. Lives were uprooted, businesses and property lost, educations interrupted.

Ochiai was among the Nisei students — the sons and daughters of Japanese immigrants who came to the United States early in the 20th century – who by order were forced leave USC, suspending his pursuit of a dentistry degree.

‘A bona fide student’

Ochiai, born Feb. 15, 1915, grew up in Riverside. He played quarterback at Riverside Polytechnic High School, competed as a swimmer and was active in the Asian American community.

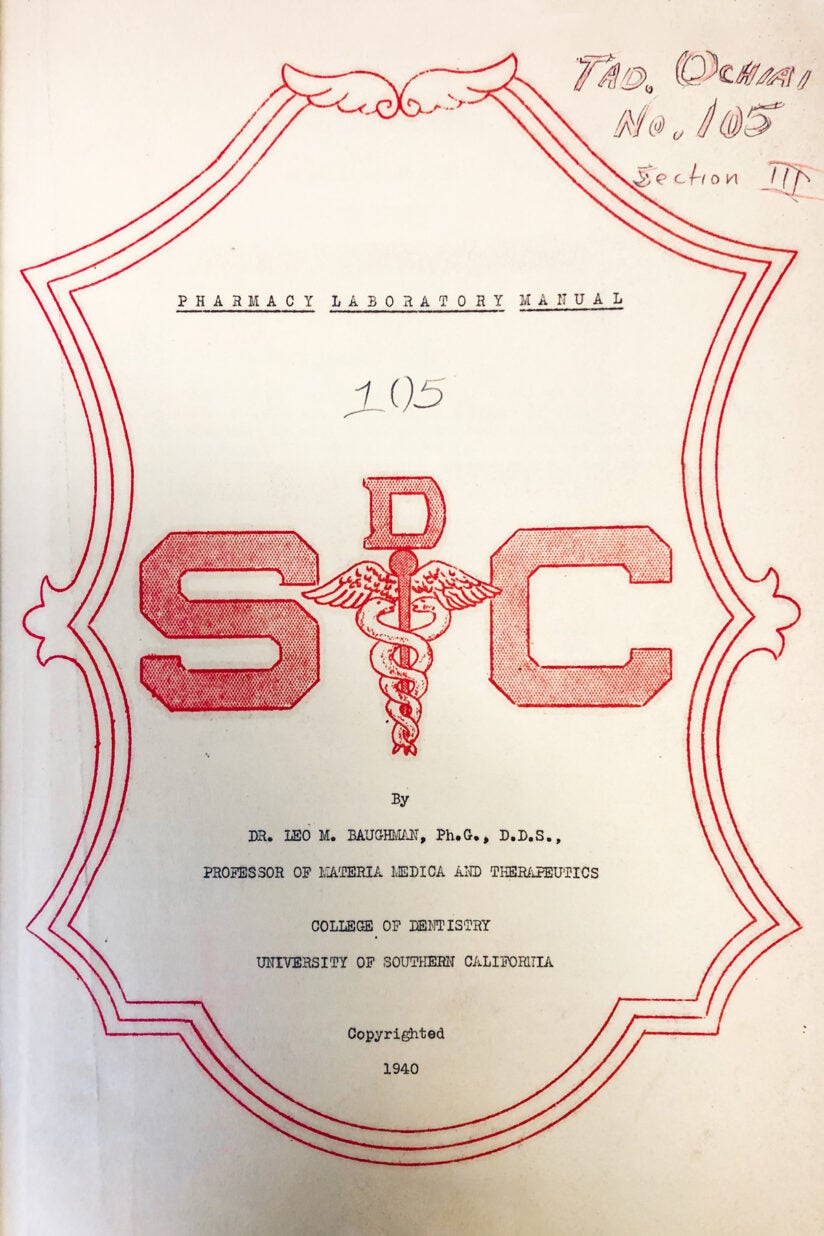

After earning his bachelor’s degree at Stanford University and obtaining a teaching credential, he enrolled at USC in 1940.

“He used to say, ‘Everything was going pretty good and then Pearl Harbor happened,’” said Kent Ochiai, Tad’s son and Niki’s uncle.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States made movement around Los Angeles perilous for Tad. The risk of police harassment or arrest was ever-present.

When he traveled from campus to his job at the postal annex on Alameda Street, he carried a typewritten letter signed by USC Dean of Men Francis Bacon.

“This young man, Tadashi Ochiai, is a bona fide student in our College of Dentistry,” it read. “He is due on the campus at 8:00 a.m. and remains in classes until 5:00 p.m.”

The letter might have protected him from police harassment, although it’s unknown whether he ever needed it.

Uprooted and moved to extremes

In 1942, Ochiai had completed his first two years of dental school at USC and was set to start his third when Roosevelt’s order took effect. Soon after, Ochiai was sent to a detention center in southwest Arizona, where he would remain incarcerated for two years.

In characteristic fashion, Ochiai made good use of the time, teaching chemistry in a rigorous high school for detainees.

“He learned how to sleep in 115-degree weather,” said his son Kent, who earned his bachelor’s and his degree in dentistry at USC in the 1980s.

“He’d soak his pajamas in water and sleep in them that way. Somehow that relieved the heat enough that he could get some rest.”

Tad was released from the detention center in 1944. He set out to resume his studies at St. Louis University, but he could not obtain his USC transcripts to prove which courses he had completed.

In some cases, USC Nisei students received transcripts from USC, allowing them to transfer to universities in the East and Midwest without needing to repeat classes. Tad, like virtually all USC dentistry students, was not as fortunate.

A new life after the war

“Nothing could really faze him,” Niki said. “I always wanted to know more about his life, but he didn’t always talk a lot about his experiences. Sometimes it was like pulling teeth to get him to talk about what he went through.”

After earning his DDS, Ochiai worked in Washington, D.C., as a dentist in the Selective Service during the Korean War era. He established his own practice in Orange County around 1950. His wife, Kay, was the office manager. Throughout his life, Tad was active in the Japanese American Citizens League, an Asian American and Pacific Islander civil rights organization.

Despite the grave injustice, Tad never broke ties with USC. He was an ardent Trojan fan. In photos taken later in his life, Tad can be seen on the football field at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Another shows him at 95 enjoying USC’s Associates Picnic in 2010. A stoic man who headed a modest family of high achievers, he talked little of his past or his troubles.

“Even though USC did that back in the ’40s, I went there, and my brother went there,” said Ruth Kawakami, Tad’s daughter and Niki’s mother.

“My parents instilled a sense of the value of education. My dad didn’t talk a lot about his troubles. It was just a different type of reaction.”

Steps toward redress

In 2012, the year Niki Kawakami graduated from Palos Verdes Peninsula High School, USC conferred honorary degrees on living Nisei students. Seventy years had passed, and most of the former students had died. A handful who were still alive received diplomas. One of them was Niki’s paternal grandfather, George Iwao Kawakami, a retired surgeon and World War II veteran who is now 100 years old. But Niki’s maternal grandfather, Tad, died two months before the ceremony.

“It was bittersweet because I got to celebrate with my [paternal] grandfather,” Niki said. “But my other grandfather wasn’t here to receive his degree.”

On April 1, the family will accept an honorary degree in Tad Ochiai’s name at a ceremony in Pasadena. The degree is the result of President Carol L. Folt’s decision to waive university policy against posthumous degrees in the case of Nisei students. In all, about 40 honorary degrees are expected to be awarded that day.

Tad’s transcripts, which could have shortened his education if he had them when he needed them, have been returned to his family.