Ruben Salazar: the Chicano journalist who paved the way for a new generation of reporters

USC Libraries has the late journalist’s writings, photographs and personal belongings, which researchers use to keep his legacy alive.

In the 1960s, long before people started using the word Latinx and calls grew loud for Latino representation in news media — Ruben Salazar was el mero mero.

The real deal. The one and only.

Born in Juarez, Mexico, and raised across the U.S. border in El Paso, Salazar was a Mexican American journalist who brought his bicultural perspective to the mainstream. He used his platform with the Los Angeles Times to tell stories about people of color with depth, compassion and nuance seldom seen at that time.

“He was a role model,” said Félix Gutiérrez, professor emeritus of journalism at USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. “He was a bilingual, bicultural, binational journalist, which one can only do when they know more than one language, are familiar with more than one culture and have lived in more than one country.”

Today, more than 50 years after his death, Salazar’s personal papers are housed at USC Libraries. They offer a wealth of insight for scholars on communication, society and Chicano history. But more on his death in a moment. First, begin with how he lived life.

Ruben Salazar: a journalism trailblazer

Salazar was a bridge between white and Mexican cultures, Gutiérrez said. He had the ability to easily build rapport with both Ivy League-educated politicians and migrant farmworkers.

He broke the mold at a time when most reporters were white men. Now, generations of Latinx reporters benefit from Salazar’s legacy.

“I think now we have a lot of Ruben Salazars,” Gutiérrez said. “Now we have many people who can fulfill that role.”

Gutiérrez remembers reading some of Salazar’s stories in the Los Angeles Times when he was a college journalism student. Salazar’s six-part series on Mexican American identity in Los Angeles, published in 1963, was particularly impactful to a young Gutiérrez. Nobody had written anything like that before. Salazar’s writings captured Gutiérrez’s own experiences.

This, thought Gutiérrez, is the kind of stuff I want to do someday.

Journalists usually covered the Mexican community in what Gutiérrez calls “zoo stories.” They portrayed Mexicans and Mexican Americans as others. Their perspective, as Gutiérrez describes it, was, “Look at these people over here.” But Salazar removed the novelty and tokenism and reported on Mexicans as part of the fabric of Southern California.

Famed L.A. journalist had his life cut short

In 1970, society simmered as protestors called for an end to the Vietnam War. Some 30,000 demonstrators from a swath of Mexican American organizations descended on East Los Angeles on Aug. 29. Called the Chicano Moratorium, it is believed to be the largest U.S. anti-war protest by an ethnic group.

By this time, Salazar was news director of Spanish-language KMEX-TV and a columnist for the Times. He and a KMEX reporter and camera operator went to cover the protest.

But Salazar never got to file his column. He died after being struck in the head by a tear gas projectile fired by a Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputy at the Silver Dollar bar, where Salazar was taking a break after covering the demonstration. He was 42 years old.

To this day, his killing causes significant controversy: Salazar himself believed that law enforcement targeted him because of his critical pieces.

Salazar’s legacy lives on at USC

Gutiérrez knew Salazar personally because he pitched stories and talked about the Chicano Movement to him. Salazar’s family remains close to Gutiérrez. So in 2011, the family donated many of the journalist’s writings, photographs and other possessions to USC. Some of it is digitized and can be viewed online. The documents are part of USC Libraries’ Boeckmann Center for Iberian and Latin American Studies.

The family’s main motivation was to ensure that his legacy is available to people who want to see it, including Salazar’s grandchildren who never met him.

“I wanted them in Los Angeles so my kids, my brother’s kids and my sister’s kids could all have a place to go and see them and look through them,” said Lisa Johnson, Salazar’s oldest daughter.

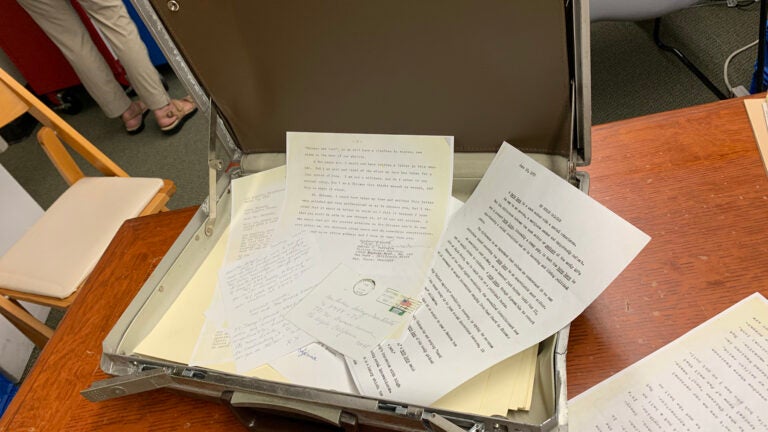

The collection includes documents like Salazar’s birth certificate from Juarez and personal letters he wrote to friends and family. In one of those letters, Salazar wrote in Spanish to his parents to say that he fell in love with a woman in Los Angeles and planned to marry her.

It also includes Salazar’s briefcase, a copy of his employment contract and letters he received from supportive and critical readers.

There are also seven boxes filled with sympathy cards delivered after Salazar’s death to his family, written by friends, relatives, colleagues and fans from around the world.

The collection also has files from the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department’s investigation into his death.

Johnson was 9 when her father was killed covering the Chicano Moratorium. Her maternal grandfather had died unexpectedly earlier that week, so Johnson remembers being at her grandmother’s house with her little sister when she heard the news.

Her grandmother, still mourning her husband’s death, couldn’t bring herself to say what happened.

“She ended up putting the front page of the Daily Pilot on the table,” said Johnson. “The headline read, ‘Newsman Salazar Slain.’ I didn’t know what the word slain meant.”

When Johnson and her sister returned home, they noticed their front lawn filled with reporters and cameras. Inside, the house was crowded with family and friends paying their respects.

Ruben Salazar collection serves as a source of history

As Johnson and her siblings grew up, she got to know her father through stories from family and friends.

She remembers reading his old clips — the same ones available in the archives — and even watching some of his old interviews. She particularly remembers an interview Salazar did with Bob Navarro titled “The Siesta is Over.”

“Hearing his voice was huge,” she said. “Seeing the way he conducted himself and answered questions so eloquently and with such passion; you could see the passion in his eyes when he talked. I was so proud of him, like, ‘Wow, that’s my dad, look at that man.’”

You could see the passion in his eyes when he talked.

Lisa Johnson

Since the family donated the collection to USC, researchers have used the materials to produce a documentary and create digital archives. Journalists also have used text and images to tell Salazar’s story.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Salazar’s death last year, USC Libraries organized an online screening of the documentary Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle, which drew from many of the pieces in the collection. USC Libraries also offers an online guide to resources about Salazar.

In addition, students of Gutiérrez and Robert Hernandez, professor of professional practice at USC Annenberg, created a digital experience of Salazar’s life. It contains links to original documents that put his life and work in context.

Earlier this year, Salazar was highlighted on his birthday, March 3, through a special virtual event supported through a Visions and Voices grant. Special Collections Librarian Barbara Robinson and Tyson Gaskill, executive director of exhibitions and programming at USC Libraries, collaborated with USC School of Dramatic Arts Professor Oliver Mayer to present Inflammatory Literature: The Legacy of American Journalist Ruben Salazar. It featured a short play by Mayer based on Salazar’s writings found in his archive in the USC Libraries’ Special Collections.

Robinson says research requests for access to the Ruben Salazar collection come in monthly.

“Those people who want to know more about him come to use these primary sources,” she said. “It’s important to have primary sources, not just secondary, because you can find evidence about things that you can’t find in a history book. The history book is based on original materials. You can see it from the voice or the view of the person who you are researching.”

Salazar’s collection at USC has helped maintain the slain journalist’s life in the public view. This is particularly important to Gutiérrez, who believes his tragic and controversial death should not distract people from what Salazar accomplished while he was still alive.

“I think there’s been more emphasis on his death than his life,” he said. “I want more people to focus on what his life was and what he represented. Is he important because of the way he died or the way he lived? I think it’s because of the way he lived.”