The possible long-term complications of traumatic brain injury

USC researcher uses sophisticated techniques to understand the effects of such injuries among older adults

After a traumatic brain injury, when do the first indications of possible long-term complications — including dementia — appear and is it possible to stave them off?

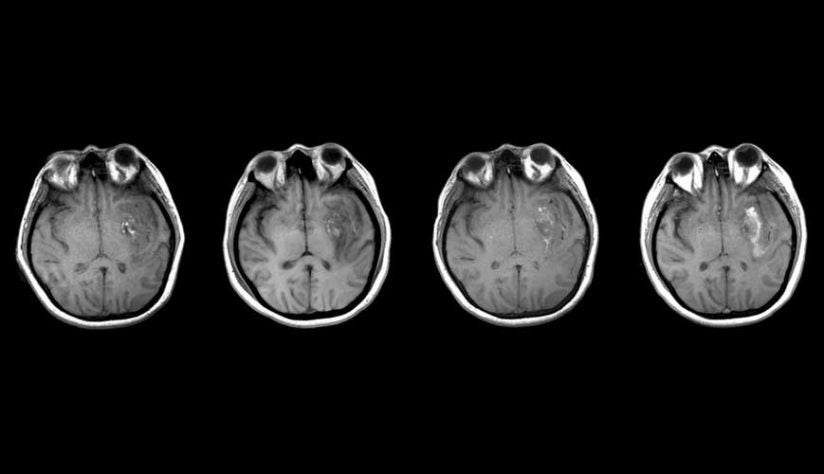

A five-year R01 grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke totaling more than $1.5 million will support one facet of brain injury research through 2021. The project will examine the effects and prognoses of small bleeds, or microhemorrhages, in the brain following traumatic brain injury in older adults.

“We want to understand whether these microhemorrhages are benign or whether they can cause serious problems for patients down the line,” said Andrei Irimia, an assistant professor at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology who uses sophisticated neuroimaging techniques to understand the effects of brain injuries and improve the quality of life of sufferers, especially older adults.

Only 2 percent of R01 grants go to researchers under the age of 35. Irimia said the grant reflects not only the increase in attention paid to the topic of brain injury itself but also the National Institute of Health’s interest in supporting precision medicine research; traumatic brain injury is a challenge that demands a personalized approach, he noted.

“No two TBIs are the same — they vary from patient to patient,” he said. “It’s difficult to study at the population level.”

Harnessing big data for brain health

Despite the extreme variability of traumatic brain injury, Irimia hopes to discover widely applicable insights for diagnosing and treating these injuries early as part of a collaboration formed during a new data science mentorship program.

The Data Science Rotations for Advancing Discovery program, or RoAD-Trip, facilitates partnerships between a junior biomedical scientist and a senior data scientist and funds two-week scientific rotations, during which the researchers work on a focused joint project involving the application of data science to biomedical research. The program is administered by the National Institutes of Health Big Data to Knowledge Training Coordinating Center.

Irimia has been collaborating with neuroinformatics expert David Kennedy, professor of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Kennedy has been training him to apply data science, cloud computing and machine-learning techniques to his neuroimaging work in hopes of identifying abnormal patterns in brain activity that indicate possible future complications of traumatic brain injury.

Wireless sensors

The two have also collaborated with Nanshu Lu, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics at the University of Texas at Austin, who studies the potential of wearable wireless sensors — akin to electronic stickers or temporary tattoos — that could one day provide constant brain activity data to physicians even when a patient is recovering at home.

The team’s eventual goal is to give physicians the ability to send mild traumatic brain injury patients home after an emergency room visit while still monitoring them remotely via easy-to-wear sensors, instead of either keeping an otherwise symptomless patient in the hospital for scans or running the risk of not catching a traumatic brain injury complication early enough. The sensors would transmit brain activity data to the computing cloud, which would analyze the patterns and alert the patient and medical team if abnormal brain activity is sensed, Irimia said.

The potential for remote monitoring and early intervention will be especially important for the older adult population, he added. As the percentage of the population over age 65 gets higher, traumatic brain injury cases are increasing, and many of those seniors living alone don’t have someone who could report complications early enough for potential treatments to be effective.

Right now, we have no way to monitor someone unless they are in a hospital and wired up.

Andrei Irimia

“About 80 percent of TBIs are mild, and the patient’s brain scan in the hospital won’t necessarily reflect the injury’s true severity. However, patients can develop complications even weeks after their release, and by the time a neurological or psychological problem reveals itself in behavior or personality changes, it may be too late to fully treat it,” he explained. “Right now, we have no way to monitor someone unless they are in a hospital and wired up. If we had a way for clinicians to remotely observe patients after their discharge and spot brain activity abnormalities as soon as they first occur, patients could undergo treatment earlier and the risk for serious problems could be reduced.”

Brain injury in older adults

Older adults face particularly high risks from traumatic brain injury, Irimia said; it’s more common in older adults than any other age group except for infants. A brain injury is also most likely to result in death when it affects a person over the age of 65, with falls being the most common cause for traumatic brain injury in older adults.

Other research shows that insults to the brain can contribute to neurodegeneration but affect individuals differently at different ages, with older people often needing more challenging treatment and not being able to recover as much as younger people, he added.

In addition, current research indicates that even when the brain injury happens in young adulthood, there is an increased risk for neurological and psychological problems decades later when the patient becomes an older adult.

Compounding the issue is the risk of stroke, which primarily affects older people but involves many of the same injury-related phenomena as traumatic brain injury. The older adult population has been relatively neglected in regard to brain injury research, Irimia noted, and individuals over 65 often need different and more challenging treatment.

“Aging with a TBI is very poorly understood,” he said.