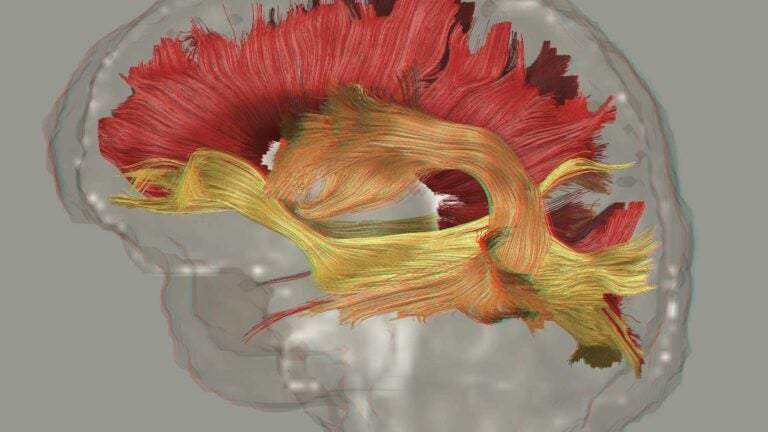

Fiber pathways in the brain are altered in schizophrenia, a mental illness in which patients may experience hallucinations, psychosis and depression. (Courtesy of Paul Thompson, Neda Jahanshad and Conor Corbin, USC Laboratory of Neuro Imaging, USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute)

Schizophrenia found to disrupt the brain’s entire communication system

Wiring is frayed in more than just one region, according to a new international study — the largest analysis ever of white matter among people with a psychiatric disorder

Some 40 years since CT scans first revealed abnormalities in the brains of schizophrenia patients, international scientists say the disorder is a systemic disruption to the brain’s entire communication system.

The study, published in the Nature journal Molecular Psychiatry on Oct. 17, sets the stage for future research on the debilitating mental illness that, according to the World Health Organization, affects more than 21 million people worldwide.

It’s the largest analysis ever of differences in “white matter” (fatty brain tissue that enables neurons to talk to each other) among people with a psychiatric disorder, and it was made possible by a federal grant to the Keck School of Medicine of USC. The study counters a theory that schizophrenia manifests due to wiring problems in only the prefrontal and temporal lobes — the front-facing areas of the brain that are responsible for personality, decision-making and hearing perception.

Frayed lines of communication, like damaged Ethernet cords, are present across the brain in those with schizophrenia, according to Sinead Kelly, co-lead author of the study.

“We can definitively say for the first time that schizophrenia is a disorder where white matter wiring is frayed throughout the brain,” said Kelly, who was a researcher at the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute at the Keck School of Medicine when the study was conducted.

Keck School of Medicine is one of the world leaders in studying brain diseases. It is the hub of several large-scale global research efforts in psychiatry, neurology and genetics.

Our study will help improve the understanding of the mechanisms behind schizophrenia.

Sinead Kelly

“Our study will help improve the understanding of the mechanisms behind schizophrenia, a mental illness that — left untreated — often leads to unemployment, homelessness, substance abuse and even suicide,” said Kelly, who is now is a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard Medical School. “These findings could lead to the identification of biomarkers that enable researchers to test patients’ response to schizophrenia treatment.”

About 1 in 4 homeless adults staying in shelter homes in America live with a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The researches found that poorly insulated brain wiring was most evident in the corpus callosum, which allows for communication between the brain hemispheres, and in the frontal portion of the corona radiata, a key structure for information processing.

Schizophrenia has a biological effect on the entire brain

Today’s medical treatment for schizophrenia addresses only its symptoms because the causes of the disease are still unknown. Many patients are asked to take antipsychotic drugs for the rest of their lives. Some experience side effects such as significant weight gain, tremors, emotional numbing or extreme drowsiness.

Previous studies on brain regions involved in schizophrenia pointed to different brain regions as culprits. Scientists need to come to a consensus on involved regions before they can begin successfully looking for causes. Aggregating and analyzing global brain scan data is critical, said Neda Jahanshad, co-lead author of the study and assistant professor of neurology at the Imaging Genetics Center within the USC Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute.

“Without this study, future research could have been misdirected,” Jahanshad said. “Rather than looking for genes that affect a certain ‘stretch of wiring,’ scientists will now look for genes that affect the brain’s entire communication infrastructure.

“We’re showing that just studying a single brain region to try to find out what causes schizophrenia is not a good approach. The effect is global. Focusing on a certain part of the brain where you think that effect will be is not going to give you the whole story.”

Largest-ever big data study on schizophrenia

Scientists analyzed the data of 1,963 people with schizophrenia and compared them to 2,359 similar, healthy people from Australia, Asia, Europe, South Africa and North America. Earlier studies typically included up to 100 people with schizophrenia, Jahanshad said.

The big data project was integrated from 29 different international studies by the ENIGMA (Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta Analysis) network, a global consortium headed by Paul Thompson at the Keck School of Medicine.

ENIGMA has published the largest neuroimaging studies of autism, major depression and bipolar disorder using brain scans of more than 20,000 people, said Thompson, associate director of the Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute.

The researchers examined data from diffusion tensor imaging, a form of MRI that measures the movement of water molecules in the white matter of the brain. These scans allow scientists to locate problem areas in the brain’s normally insulated communication system.

The study paves the path for more focused scientific inquiry. A next step could be to seek what causes these abnormalities in white matter. Schizophrenia is partly hereditary, so perhaps specific genes promote the disorder via slight alterations in brain wiring, Kelly said.

USC has researchers across disciplines seeking to prevent or treat neurological and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy.

Gary Donohoe from the National University of Ireland Galway, Andrew Zalesky from the University of Melbourne in Australia, Annerine Roos from Stellenbosch University in South Africa, Zora Kikinis from Harvard Medical School and Ryota Hashimoto from Osaka University in Japan are among the 160 scientists from 27 institutions and hospitals who contributed to this study.

The study was funded by private and federal agencies worldwide, including an $11 million grant from the NIH Big Data to Knowledge initiative given to Thompson and colleagues (U54EB020403).