Why innocent people plead guilty

Federal judge says thousands are in prison after taking deals

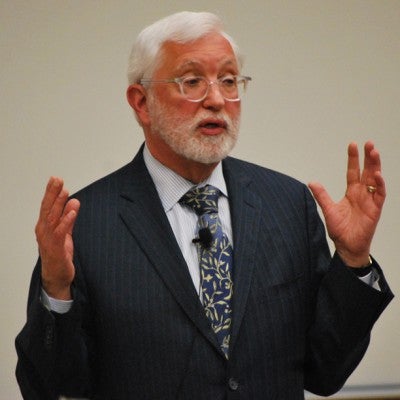

After serving as a criminal defense attorney, federal prosecutor and now United States District judge, the Hon. Jed Rakoff knows what works — and what doesn’t — in the criminal justice system.

Rakoff, who sits on the Federal District Court in Manhattan, N.Y., spoke recently at the USC Gould School of Law’s Neiman Sieroty Lecture on “Why Innocent People Plead Guilty.” The annual talk is named for Allen Neiman ’56 and Alan Sieroty ’56, who were former classmates and law partners.

“The criminal justice system is nothing like you see on TV — it has become a system of plea bargaining,” Rakoff said.

Today, only 2 percent of cases in the federal system go to trial, and 4 percent of cases in the state system go before a jury. As a result, accepting a deal from prosecutors — despite one’s guilt or innocence — has become a common choice for individuals accused of a crime.

“Plea bargains have led many innocent people to take a deal,” Rakoff said. “People accused of crimes are often offered five years by prosecutors or face 20 to 30 years if they go to trial. … The prosecutor has the information, he has all the chips … and the defense lawyer has very, very little to work with. So it’s a system of prosecutor power and prosecutor discretion. I saw it in real life [as a criminal defense attorney], and I also know it in my work as a judge today.”

A controversial solution

What can be done? Rakoff said prosecutors should have smaller roles in sentence bargaining and the mandatory minimum sentences should be eliminated.

“But to be frank, I don’t think, politically, either of those things is going to happen. … When it comes right down to it, I think the public really wants these high penalties, and that’s because when these harsh penalties were imposed [in the 1980s], the crime rate went down.”

Another more controversial solution is to allow judicial involvement in the plea bargain process. A judge who is not involved in the case could take a first pass at an agreement, working with prosecutors and defense attorneys.

“What I have in mind is a magistrate judge or a junior judge would get involved,” Rakoff said. “He would take offers from the prosecutor and the defense. … He would evaluate the case and propose a plea bargain if he thought that was appropriate, and he might, in appropriate cases, say to the prosecutor, ‘You don’t have a case and you should drop it.’ This would be very difficult for the judiciary; it’s not something I come to lightly, but I can’t think of any better solution to this problem.”

Until extraordinary action is taken, Rakoff said little will change.

“We have hundreds, or thousands, or even tens of thousands of innocent people who are in prison, right now, for crimes they never committed because they were coerced into pleading guilty. There’s got to be a way to limit this.”