A new study by researchers at USC explains why kids aren’t getting a cheap, effective treatment for diarrhea.

Contact: Nina Raffio, raffio@usc.edu or 213-442-8464; Jenesse Miller,jenessem@usc.edu or 213-810-8554

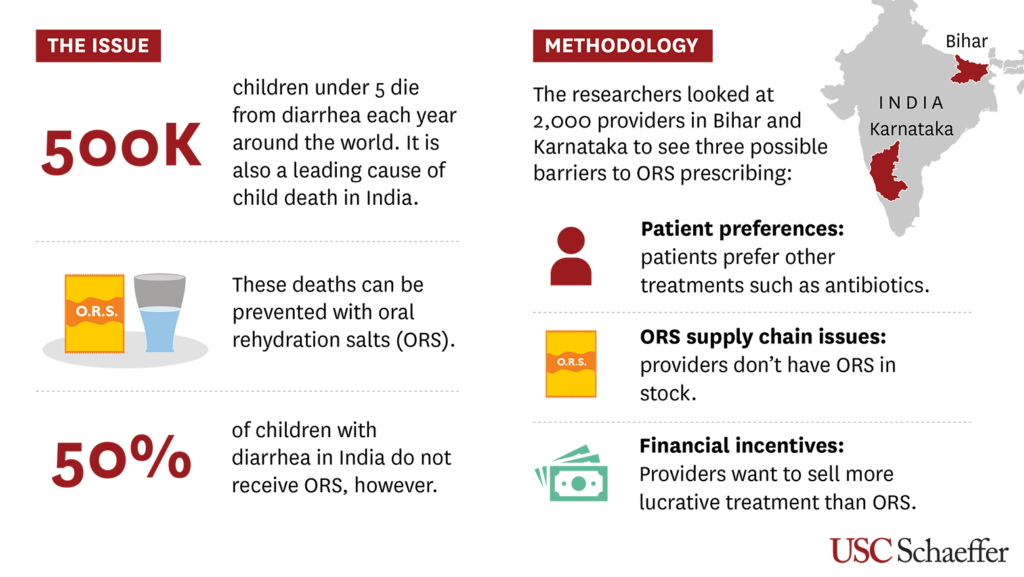

Health care providers in developing countries know that oral rehydration salts (ORS) are a lifesaving and inexpensive treatment for diarrheal disease, a leading cause of death for children worldwide — yet few prescribe it.

A new study published in Science suggests that closing the knowledge gap between what treatments health care providers think patients want and what treatments patients really want could help save half a million lives a year and reduce unnecessary use of antibiotics.

“Even when children seek care from a health care provider for their diarrhea, as most do, they often do not receive ORS, which costs only a few cents and has been recommended by the World Health Organization for decades,” said Neeraj Sood, senior author of the study, senior fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and a professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

“This issue has puzzled experts for decades, and we wanted to get to the bottom of it,” said Sood, who also holds joint appointments at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and the USC Marshall School of Business.

A closer look at childhood illness in India

There are several popular explanations for the underprescription of ORS in India, which accounts for the most cases of child diarrhea of any country in the world:

- Physicians assume their patients do not want oral rehydration salts, which come in a small packet and dissolve in water, because they taste bad or they aren’t “real” medicine like antibiotics.

- The salts are out of stock because they aren’t as profitable as other treatments.

- Physicians make more money prescribing antibiotics, even though they are ineffective against viral diarrhea.

To test these three hypotheses, Sood and his colleagues enrolled over 2,000 health care providers across 253 medium-size towns in the Indian states of Karnataka and Bihar. The researchers selected states with vastly different socioeconomic demographics and varied access to health care to ensure the results were representative of a broad population. Bihar is one of the poorest states in India with below-average ORS use, while Karnataka has above-average per capita income and above-average ORS use.

The researchers then hired staff who were trained to act as patients or caretakers. These “standardized patients” were given scripts to use in unannounced visits to doctors’ offices where they would present a case of viral diarrhea — for which antibiotics are not appropriate — in their 2-year-old child. (For ethical considerations, children did not attend these visits.) The standardized patients made approximately 2,000 visits in total.

Providers were randomly assigned to patient visits where patients expressed a preference for ORS, a preference for antibiotics or no treatment preference. During the visits, patients indicated their preference by showing the health care provider a photo of an ORS packet or antibiotics. The set of patients with no treatment preference simply asked the physician for a recommendation.

To control for profit-motivated prescribing, some of the standardized patients assigned as having no treatment preference informed the provider that they would purchase medicine elsewhere. Additionally, to estimate the effect of stockouts, the researchers randomly assigned all providers in half of the 253 towns to receive a six-week supply of ORS.

Provider misperceptions matter most when it comes to ORS underprescribing

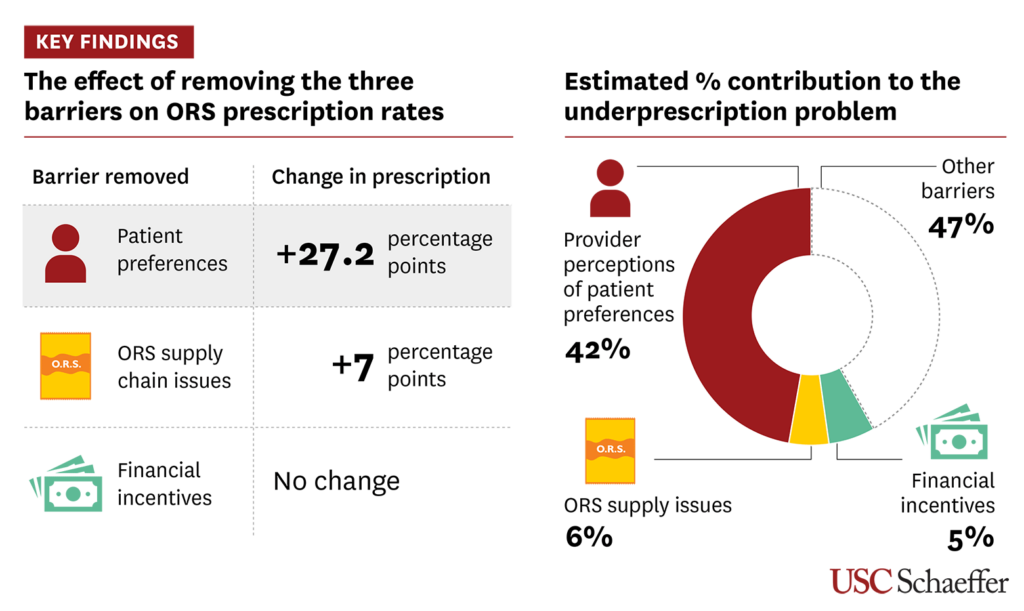

Researchers found that provider perceptions of patient preferences are the biggest barrier to ORS prescribing — not because caretakers do not want ORS, but rather because providers assume most patients do not want the treatment. Health care providers’ perception that patients do not want ORS accounted for roughly 42% of underprescribing, while stockouts and financial incentives explained only 6% and 5%, respectively.

Patients expressing a preference for ORS increased prescribing of the treatment by 27 percentage points — a more effective intervention than eliminating stockouts (which increased ORS prescribing by 7 percentage points) or removing financial incentives (which only increased ORS prescribing at pharmacies).

“Despite decades of widespread knowledge that ORS is a lifesaving intervention that can save lives of children suffering from diarrhea, the rates of ORS use remain stubbornly low in many countries such as India,” said Manoj Mohanan, co-author of the study and professor of public policy, economics, and global health at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. “Changing provider behavior about ORS prescription remains a huge challenge.”

Study authors said these results can be used to design interventions that encourage patients and caretakers to express an ORS preference when seeking care, as well as efforts to raise awareness among providers about patients’ preferences.

“We need to find ways to change providers’ perceptions of patient preferences to increase ORS use and combat antibiotic resistance, which is a huge problem globally,” said Zachary Wagner, the study’s corresponding author, an economist at RAND Corporation and professor of policy analysis at Pardee RAND Graduate School. “How to reduce overprescribing of antibiotics and address antimicrobial resistance is a major global health question, and our study shows that changing provider perceptions of patient preferences is one way to work toward a solution.”

About the study

In addition to Sood, Wagner and Mohanan, co-authors of the study include Rushil Zutshi of RAND Corporation and Pardee RAND Graduate School and Arnab Mukherji of the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore.

This research was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant 5R01DK126049).