“Dr. Robin” — USC Annenberg Associate Professor Robin Stevens (front row, center left) — shares a moment with program participants. (Photo/Areon Mobasher)

USC – IG Codesign Scholars program hopes to inspire the innovators of tomorrow

The program, a collaboration between USC Annenberg and the parent company of Instagram and Facebook, offered underrepresented students from L.A. schools an opportunity to improve social media’s mental health impact on young people.

High school senior Xavier Guillory of Augustus Hawkins High School in Los Angeles remembers the first time he mustered up the courage to share one his ideas during his internship with the USC – IG Codesign Scholars. The program, a collaboration between Meta and the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, gave 14 Black and Latino students from schools across L.A. a seat at the design table to help the company develop programming to improve social media’s mental health impact on youth.

“There were a lot of moments in the program where they’d ask us questions and I’d look around the room and it’s very silent and it’s awkward,” Guillory said. “We’re all teenagers. We have anxiety, and we don’t want to share something wrong.”

On that day he decided to share his ideas — which included an increased use of avatars and shortcuts on Instagram — and nervously waited to be shot down. The praise and constructive conversation that followed taught Guillory an important lesson.

“I learned that no idea is too small or too big,” he said. “If you feel like people may not like it, just share it out. You have to take risks.”

In mid-September, Meta introduced Teen Accounts, an incoming feature on their platforms where users under 16 years old are opted into social media accounts with protections and can only opt out with parental consent. The change — which Meta says will eventually be made globally — is designed to limit young people’s exposure to high-risk content and could affect millions of teen users.

Meta said the new changes were made in consultation with its Safety Advisory Council and youth advisors — including the USC – IG Codesign Scholars.

“Just seeing that people of all ages can make an impact on something as big as Instagram all over the world is motivating,” said Jadon Elzy, a participating sophomore at Da Vinci Connect High School in El Segundo, whose older brother is a sophomore at the USC Marshall School of Business. “It motivates me to keep doing what I’m doing and lets me know that I’m on the right path.”

Instilling that kind of confidence is just one of the goals of program leader Robin Stevens, a USC Annenberg associate professor of communication who also serves as the school’s associate dean for research.

“The whole point of my career is about health equity, trying to improve outcomes for Black communities and disrupting disparities,” said Stevens, who has taught at USC for four years and has conducted community-based research on youth of color for nearly two decades. She hopes that the experience will teach students the power of their voices and unique expertise. She also hopes the program shows social media researchers and developers that young people of color need to play an active role in efforts to improve social media’s mental health impacts and strengthen protections from potential harms.

The program aligns with USC President Carol Folt’s Frontiers of Computing “moonshot,” which promotes the ethical use of technology in tackling society’s most pressing issues.

“Dr. Stevens’ work is the best integration of research, technology and equity,” says Professor Hector Amaya, director of the School of Communication at USC Annenberg. “She shows us the way to do ethical research and how we can partner with digital giants like Meta to pursue socially minded goals.”

Supporting the innovators of tomorrow

Recruiting for the USC – IG Codesign Scholars program began in October 2023. Drawing from the community partnerships she’d made in her short time in L.A. to recruit students, Stevens reignited a past collaboration with Meta employees who were interested in making sure that Instagram was supportive of teen mental health. USC alum Elizabeth Inglese, content design manager for Instagram Well-being, served as Stevens’ counterpart and advocate on the Meta side.

Stevens and her team at USC Annenberg — which included students from her doctoral program — selected from all grades at seven different high schools across the L.A. Unified School District and one charter school with a focus on Black and Latino students with diversity in gender and sexuality.

Before the program began, Stevens hosted “ethical positioning” meetings between her team and participating Meta staff to ensure that the program left students feeling empowered rather than studied.

“It was very intentional,” Stevens said. “I was not going to put the students in a situation where people are just taking from them. It had to be a mutually beneficial process.” This included paying the students for their time and transportation and covering meals.

The first few meetings with students started in February without any Meta representation. Early gatherings included team building and exercises on using their voice and learning how to critique and argue ideas.

“‘Dr. Robin’ made the environment so relaxing that everyone just felt like they were friends from the get-go,” said Samantha Valencia, a participating senior at Theodore Roosevelt High School.

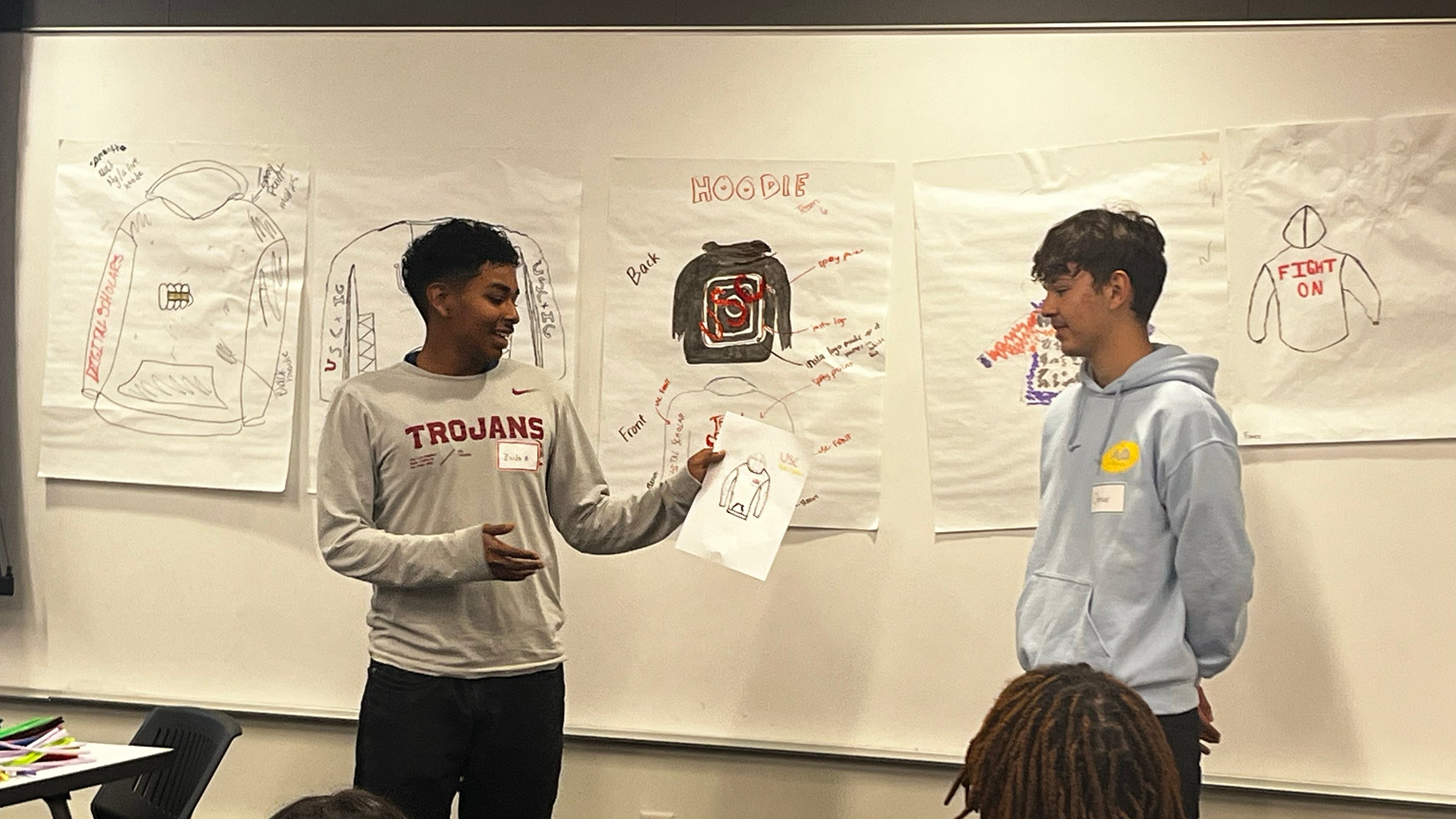

From March to June, the program held codesign sessions in collaboration with six Meta staff members, including graphic and content designers and some from the company’s research arm. The goal of each session was to get students used to sharing ideas and working in a team setting while building up their voices and critical thinking skills.

“Those sessions allowed me to expand upon skills that I probably already had and gain a few new ones,” Elzy said. “One was the ability to freely speak with professionals and give them insights — not just listening to someone but putting out your own point. Hearing ideas and expanding upon them.”

Students also received free training on Figma, an industry standard software for developing and designing apps and other digital products.

“It was definitely one of the best, if not the best program I’ve ever participated in,” Elzy said. “I was one of the youngest people there, and it was interesting to meet a lot of like-minded individuals, but not in the same age group.”

The program culminated with a final presentation in June in front of Meta staff and the parents of participating students, where the scholars presented apps they had developed during the program or discussed apps they hope to design in the future.

Digital neighborhoods

For Stevens, whose initial research centered on youth sexual health, a focus on social media was inevitable. “Because my work is community-engaged, young people forced me to talk about technology and media,” Stevens said. “That’s where a lot of their health conversations were happening — in the digital space.”

These insights led Stevens to develop the concept of “digital neighborhoods.” While public health research had a good understanding of how geographic neighborhoods could affect health, Stevens argued that, for the next generation, digital neighborhoods could also have an impact.

While writing a paper titled “The Digital Hood,” Stevens learned through conversations with young people that there was a “huge gap” between the critiques of social media and digital spaces largely driven by white teenagers and what Black and Latino youths were experiencing, which was largely absent from the conversation.

What’s missing from the conversation

Predominant themes of the social media experiences of white youths included internet addiction, bullying and body dysmorphia. Stevens said these themes then informed policy and the national conversation around internet safety. For kids of color, however, “things that are happening on social media spill out and the things that happen in the neighborhood spill onto social media,” Stevens said. With online conflicts amplified on social media turning into real-life violence, the stakes appeared much higher.

“They’re the innovators and the early adopters,” said Stevens, who argued that no one was protecting Black youth from the harms of digital spaces because there was no awareness about the dangers that they experience. “They’ll take a platform, turn it upside down, create amazing content and make the platform the platform to be on. Despite this, we see it over and over where Black youth are technologically innovative, culturally leading and marginalized in that same technology.”

After concluding that the policies being made to protect youth online did not reflect the Black and Latino experience — nor acknowledge the role they play in creation on those platforms — Stevens felt the arena was ripe for innovation.

“The thing that I don’t think people realize is, if you study the middle, you get the middle,” Stevens said. “But if you study folks on the margins, that’s where you get the innovation. And it’s where also, you start to see the first signals of challenge and how people are going to misuse or use your product — it gives you so much more insight.”

Stevens began her professorial career at Rutgers University before moving on to the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Nursing, where she created the school’s Health Equity and Media Lab. During this time, she first started building the methodology to better understand young people’s online habits and incorporate high school students and community members into the research process as experts rather than just subjects.

Independent research from Stevens’ team analyzed journals, surveys and interviews with the USC – IG Codesign Scholars to assess the impact of the program and found increased perceived leadership skills across the board.

With the conclusion of the program and the development of Teen Accounts, Stevens sees the culmination of her efforts to move away from extractive research and explore the different roles young people can play in solutions that promote their own well-being.

“A spotlight should really be placed on the teenagers for this — they really did the work,” Stevens said. “I was more the conductor of all of this. I didn’t play any instruments. They made the music.”