Internal Logic: Whole-Brain Atlas of Neural Networks Reveals Eight Distinct Subnetworks in Mouse Cerebral Cortex

“Think about it: the brain is built for logic, so its organization must be logical.”

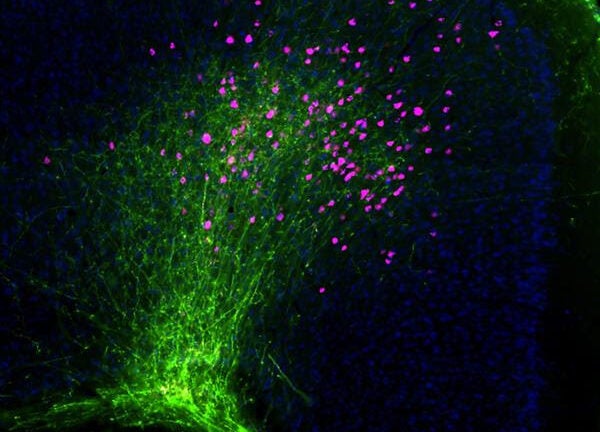

[Image caption: Fluorescent dyes labeled axons (green) and projection neurons (pink) in the mouse neocortex. Courtesy of the USC Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics.]

Contact: Suzanne Wu atsuzanne.wu@usc.edu or (213) 740-0252; Eddie North-Hager at (213) 740-9335 oredwardnh@usc.edu

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE 9 A.M. PT/12 P.M. ET, FEB 27, 2014 — The mammalian cerebral cortex, long thought to be a dense single interrelated tangle of neural networks, actually has a “logical” underlying organizational principle, reveals a study appearing Feb. 27 in the journal Cell.

Researchers have identified eight distinct neural subnetworks that together form the connectivity infrastructure of the mammalian cortex, the part of the brain involved in higher-order functions such as cognition, emotion and consciousness.

“This study is the first comprehensive mapping of the most developed region of the mammalian brain: the cerebral cortex. The cortex is highly complex and made up of many densely interconnected structures, but when you strip it down, is organized into a small number of subnetworks,” said senior author Hongwei Dong of the USC Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics.

The cerebral cortex is the outermost layer of neural tissue in the brain and is one of the most extensively studied brain structures in the field of neuroscience. However, before this study, its underlying organizational principle was still largely unclear.

“Think about it: the brain is built for logic, so its organization must be logical. The brain’s architectural organization is arranged such that all of its substructures most efficiently work in conjunction to produce appropriate behaviors, ” said Dong, associate professor of neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “We want to find the code to how the brain is structurally organized.”

The study is also a reminder that while there is more data than ever, the quality and reliability of information still matters. In contrast to past patchwork attempts, Dong and his team undertook an effort to directly develop a whole-brain mouse atlas of brain pathways. Across the cortex, they injected fluorescent molecules. These molecules were then transported along the brain’s “cellular highways” — the neuronal pathways — and meticulously tracked using a high-resolution microscope.

The uniformity and completeness of the scientists’ effort across the entire cortex not only provided for a searchable image database of cortical connections, which the researchers are making open-access and publicly available.

It also allowed them to reliably see patterns: the seemingly inscrutable mass of connections in the cerebral cortex is highly organized, consisting of eight distinct subnetworks that are relatively segregated.

“The systematic and comprehensive manner in which the data were collected lent itself to a detailed analysis through which these subnetworks emerged,” explained co-lead author Houri Hintiryan of the USC Laboratory of Neuro Imaging.

So that scientists around the world may continue to look for fundamental structural insights, the full, interactive imaging dataset is viewable at Mouse Connectome Project, providing a resource for researchers interested in studying the anatomy and function of cortical networks throughout the brain.

“It really is quite tedious,” Dong said of collecting the data, “and labor-intensive, and it requires highly specialized skills and technology. But think of the Human Genome Project and how much it accelerated the process of discovery and the whole field when infrastructures existed for people to share and compare. That was our motivation.”

How these subnetworks interact will provide a crucial baseline from which to better understand diseases of “disconnection” such as autism and Alzheimer’s Disease, in which the manifestations of symptoms are potentially a result of disordered or damaged connections.

The researchers’ map of the mouse cerebral cortex can be compared to data on disease-affected brains, brains in development and genetic information. It will also offer necessary context for some of the particularities of being human, who behaved just like other mammals only a few thousand years ago and who still share most underlying basic behavioral characteristics such as hunger and pain.

“The fundamental logic of mammalian brains is the same, particularly when it comes to basic behaviors such as eating, sleeping, and social behaviors” said Dong, who notes that similar studies in humans have thus far not gotten to the cellular level. “There are lots of organizing principles to brain structures that we are just beginning to understand.”

The researchers identified the brain subnetworks based on their high degree of interconnectivity — though relatively independent, several structures provide communication routes through which the subnetworks interact. Combined with behavioral data from past research and information about subcortical targets, these interconnections imply remarkable functional significance for the subnetworks.

Four of the eight identified subnetworks in the mouse cortex relate to sensation and movement of the body, what the researchers dub somatic sensorimotor. In particular, the researchers identified separate subnetworks for movements in the face, upper limbs, lower limbs and trunk, and whiskers. Together, these networks facilitate motor behaviors such as eating and drinking, reaching and grabbing, locomotion and exploration of the environment.

Two other subnetworks are comprised of structures located along the midline of the cerebral cortex. These medial subnetworks seem devoted to the integration of visual, auditory and somatic sensory information, according to the study. Several other structures located along the side of the brain form two lateral subnetworks, one of which potentially serves to regulate the internal status of the body (i.e. taste, hunger, visceral information) and the other as a “mega-integration” subnetwork that allows the interaction of information from nearly the entire cortex.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (grants: MH094360-01A1 and 3P41RR013642-12S3). Brian Zingg of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at USC was co-lead author of the study. Arthur Toga, director of USC INI, was also an author of the study.

For more information or to request an interview with a researcher, contact Suzanne Wu atsuzanne.wu@usc.edu.

About the USC Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics

The Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics aims to enhance discovery through the application of imaging and information technologies in the study of the brain. The Institute is dedicated to excellence in data acquisition, analysis, stewardship and computational innovation for the purpose of biomedical research.

About Digital USC

Digital USC is a university-wide initiative of $1 billion over 10 years towards gathering, interpreting and applying digital data on a massive scale. An international leader in fields from artificial intelligence to game design, with the largest computer science research program among American universities, USC is advancing knowledge in the development of virtual humans for therapy, entertainment, or historic preservation; the simulation and modeling of earthquakes and other complex systems; brain mapping; archiving, indexing and analysis of visual material; visual storytelling and data visualization; and in creating advanced online platforms for distance education and professional development.