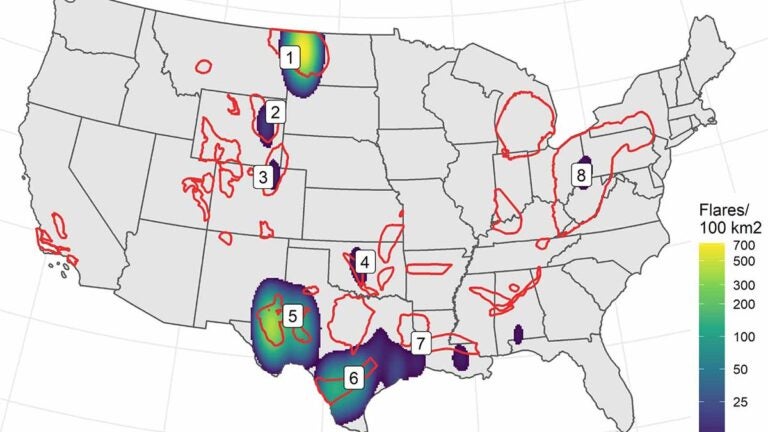

This map shows the density of flares near oil- and gas-rich fracking sites: (1) Williston, (2) Powder River, (3) Denver, (4) Anadarko, (5) Permian, (6) Western Gulf, (7) TX-LA-MS Salt and (8) Appalachian basins. (Graphic/Courtesy of Keck School of Medicine of USC and the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health)

Health risk? More than 500,000 Americans live within 3 miles of natural gas flares

A USC-UCLA study offers nationwide assessment of the population facing exposure risks from burned-off, excess natural gas at oil and gas production sites.

More than a half-million Americans are exposed to oil and gas “flaring” events — the burning off of excess natural gas at production sites — resulting in potentially serious health risks, according to new research from USC and UCLA.

“Our findings show that flaring is an environmental justice issue,” said Jill Johnston, an environmental health scientist and assistant professor of preventive medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“We found that a significant number of Black, Indigenous and Latinx people live near flaring. High rates of poverty and other barriers to health in rural areas — such as a lack of access to health care — could worsen the health effects of flaring-related exposures.”

The report, published recently in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Research Letters, found that three oil- and natural gas-rich regions in the United States are responsible for most flaring activity in the lower 48: the Permian Basin (Texas-New Mexico), Western Gulf Basin/Eagle Ford Shale (Texas) and the Williston Basin/Bakken Shale (North Dakota and Montana). Some 535,000 people live within 3 miles of flaring sites in these regions. Of those, 39% — roughly 210,000 people — lived near more than 100 nightly flare events.

“There is growing evidence linking residence near unconventional oil and gas operations with negative health impacts for nearby residents, including impacts on fetal growth and preterm birth,” said Lara Cushing, assistant professor of environmental health sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and co-lead of the study.

“This includes our recent finding that living within about 3 miles of flaring is associated with increased risk of preterm birth.”

Flaring is used during the exploration, production and processing of fossil fuels, and it is common in oil-producing areas where natural gas recovered with the oil cannot be used commercially. Air quality monitoring studies have indicated that flares — which often operate continuously for days or weeks — release a variety of hazardous air pollutants, including volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and black carbon.

Health risks of flaring could affect residents of 714 counties, 28 states

Along with links to preterm births and other adverse birth outcomes, these pollutants contribute to the development and exacerbation of asthma and effects on the respiratory, cardiovascular and nervous systems, as well as cardiopulmonary problems and cardiovascular mortality. These regions have high levels of poverty and large populations of people of color, including Native Americans in North Dakota and Montana — particularly members of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation living on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation — and Black and and Hispanic people in Texas and New Mexico.

Researchers used data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration to define the boundaries of all oil and gas shale production areas in the contiguous United States. The data, updated in 2016, include 47 shale plays within 28 basins that intersect 714 counties across 28 states.

The team estimated the density of nightly flares (count per square kilometer) across all 28 basins. Then, the researchers narrowed the study and refined estimates for those with the most flaring — the Permian in Texas-New Mexico, Western Gulf Williston in Montana-North Dakota and Williston in Montana-North Dakota.

The researchers focused on well data from horizontal- and directional-drilled wells that were actively producing from March 2012 through February 2020. Flares were identified with the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite instrument Nightfire technology from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth Observation Group.

The researchers also utilized data from the 2010 U.S. Census and the 2018 American Community Survey, as well as a national dataset of building footprints to identify populations living near flaring.

In addition to Johnston and Cushing, the study’s other authors were Khang Chau and Meredith Franklin, both of USC.

The work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R21-ES028417).