Antidepressants May Fight Brain Cancer

A USC-led research team finds that antidepressants can stifle a behavior-altering enzyme and shrink drug-resistant brain tumors that currently have no treatment.

Contact: Michele Keller at (213) 210-6072 or kellermi@usc.edu; Emily Gersema at (213) 361-6730 or gersema@usc.edu

Contact: Michele Keller at (213) 210-6072 or kellermi@usc.edu; Emily Gersema at (213) 361-6730 or gersema@usc.edu

Antidepressants can shrink and stunt cancerous brain tumors that are otherwise difficult to treat, an international team of researchers has found.

USC School of Pharmacy researchers who led the study on mice found that the drugs stifle the growth of brain cancer, glioma or glioblastoma, by suppressing the enzyme “monoamine oxidase A,” which affects the release of emotional brain chemicals such as dopamine and serotonin.

“Until now, patients diagnosed with these drug-resistant tumors have had no treatment options,”said Jean Chen Shih, University Professor at the USC School of Pharmacy and the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “Antidepressants could be a potential treatment, slowing down the cancer growth and extending the lives of patients.”

Few options

Glioblastoma, the most aggressive form of malignant brain tumor, usually becomes resistant to standard treatments, at which point there are no further treatment options. An estimated 13,000 Americans die from brain cancer each year, according to the National Cancer Institute. The median age of a patient diagnosed with glioblastoma is 64. Patients live an additional 14 months on average after diagnosis.

Typically, brain cancer is treated with TMZ — temozolomide — an oral drug that attacks the DNA of the tumor cells. Some tumors become resistant to TMZ.

Disrupting cancer

Shih and her collaborators found that the MAO-A inhibitors reduce cell proliferation and increase immune response. Their study was published on Feb. 9 in the journal Oncotarget.

“Our data identified the MAO-A inhibitors as potential novel stand-alone drugs, or as a combination therapy with a low-dose of the current treatment, TMZ, thus reducing the toxicity of TMZ,” said Shih, who is also the director of the USC-Taiwan Center for Translational Research. “We hope to do a clinical study in the near future to learn if this finding in animals will be applicable in humans.”

The study builds upon prior research that showed antidepressants can also reduce prostate cancer progression and metastasis.

Shih, who has spent decades studying the enzyme and brain development, collaborated with Florence M. Hofman and Thomas Chen of the Keck School of Medicine of USC, experts in glioma research.

Other USC School of Pharmacy faculty members involved in the study were Kevin Chen, a molecular biologist, and Bogdan Olenyuk, an expert in chemistry synthesis, as well as Keck School of Medicine professor Susan Groshen.

The study was funded by the Daniel Tsai Family Fund, USC-Taiwan Center for Translational Research, and the National Institutes for Health [RO1 MH39085].

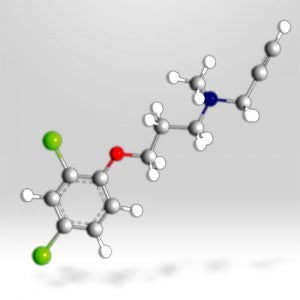

Graphic: This illustration depicts the makeup of the antidepressant/MAO-A inhibitor, clorgiline. Courtesy of the USC School of Pharmacy.