This Black History Month, better understand the role of the Black family

USC experts weigh in on the Black family, which has been “reverenced, stereotyped and vilified from the days of slavery to our own time,” according to the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

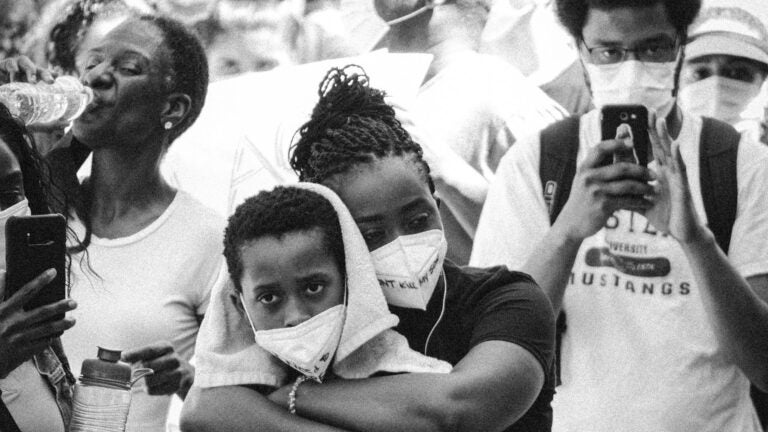

The national theme of Black History Month this February is the Black family — a focus of study in various disciplines such as history, anthropology, literature, sociology and the arts. The Association for the Study of African American Life and History, which decides the theme each year, says the Black family has been “reverenced, stereotyped and vilified from the days of slavery to our own time.”

USC professors weigh in on Black achievements that are cause for celebration, as well as challenges that still need to be solved by all Americans.

USC professors weigh in on Black achievements that are cause for celebration, as well as challenges that still need to be solved by all Americans.

The importance of understanding Black history and excellence

“At a time of growing awareness about racial injustice and systemic racism in the U.S., the need to understand Black history has never been more important,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of the USC Rossier School of Education.

“Throughout our history on this continent, Black people have been subjected to violence, degradation and unrelenting discrimination,” he said. “Despite this adversity, we have survived and often thrived. If one thinks of just a few recent Black names in the news — baseball legend Hank Aaron, inauguration poet Amanda Gorman, director and actor Regina King and our new Vice President Kamala Harris — it is clear that, despite the challenges we face, Black people continue to excel.

“While enormous challenges remain, due to systemic racial inequality and the corresponding racial disparities in academic outcomes and opportunities, education remains our best hope for a more just future,” he added. “It is the key to continued Black excellence.”

Black families torn apart by slavery, prisons and pandemic

Enduring slavery, segregation and Jim Crow, and persistent structural racism has come at a painful cost to Black families, said Alaina Morgan, an assistant professor of history at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

“American legislators run their platforms on ideas of ‘family values’ and the ‘sanctity of the family,’ but support for Black families has always been excluded from these imperatives,” said Morgan, who researches the institutional structures that destabilize the Black family along with stabilizing forces such as religion, particularly Islam.

Education remains our best hope for a more just future.

Pedro Noguera

“Black families have always occupied a precarious social position, dating back to the antebellum period when Black men and women could not be legally married, Black children were not permitted the luxury of acting as such, and Black mothers and fathers never knew when they could be shipped to a different plantation,” she said.

“Today, with rates of mass incarceration ripping Black men and increasingly Black women away from children and COVID-19 killing Black people at disproportionately higher rates, the Black family remains under attack.”

Racism continues to be a hazard to Black families’ health

The newest threat to the Black family, the COVID-19 pandemic, is especially lethal because of another ongoing pandemic.

“For centuries, Black families have shouldered the ramifications of discrimination and structural racism,” said April Thames, associate professor of psychology and psychiatry at USC Dornsife and the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “This is glaringly evident when examining Black-white disparities in health, health care and racial trauma.”

Thames, who recently authored a study that showed that genes that promote inflammation are expressed more often in Blacks than in whites, said exposure to racism factors into the disparities in health outcomes, including illness and death from COVID-19.

“Health disparities are tied to the biological impact of racism on health as well as blocked opportunities to access equitable and optimal health care,” she explained. “Historic displacement, exclusion and segregation of Black families across the country continues to be a deadly threat to the physical and mental health of Black Americans.”

The Rev. Najuma Smith-Pollard, a pastor and program manager for USC Dornsife’s Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement, described attending to Black families who can barely grieve one death before they learn of another family member succumbing to the coronavirus. “Black History Month feels like a cheap consolation prize for all that Black families are enduring, including suspended grief — grief that they can’t actually process because there are too many deaths,” she said.

Despite the challenge of celebrating much of anything, she added, in honor of Black History Month “we will look to the narratives of our ancestors, the trailblazers and the legend makers, and we will find hope and create some new stories.”

An unknown piece of Black, and LGBTQ, history

Those new stories can sometimes be found in hidden history. In addition to celebrating civil rights giants such as Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Malcolm X, Black History Month can provide an opportunity to learn about lesser-known figures who left an indelible mark.

Cultural historian and journalist Channing Gerard Joseph explores one such example in his forthcoming House of Swann: Where Slaves Became Queens, a book about the true story of a formerly enslaved Black man who became the world’s first self-described drag queen.

Black families are roses growing in the midst of concrete.

Najuma Smith-Pollard

“William Dorsey Swann was as out as you could be in the 19th century — so out that the president of the United States knew about him,” said Joseph, a journalism lecturer at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. “In Washington D.C., where he lived, it was well-known that he was the leader of a queer community. He was the first documented person to use the word ‘queen’ to describe himself in the context of a ball or party that was described by participants as a drag.

“During his lifetime he was sent to jail numerous times and faced beatings, losing a job and losing friends, all because of his effort to build a community around queerness and drag in the 19th century,” he added. “My hope is that, over time, people could understand his contribution to creating this world and that we could all honor him by acknowledging the roots of drag in America.”

Finding hope and thriving against the odds

It isn’t just the outsized, headline-grabbing achievements that should be celebrated during Black History Month, noted USC historian Morgan. “One of the things that I would love to see during Black History Month is moving away from just thinking about Black activists and leaders and thinking about what it is that normal people do every day to fight institutional racism, oppression, brutality and violence — including this enormous task of keeping the Black family strong,” she said.

Smith-Pollard agreed that the resilience of Black families should be acknowledged. She provided examples of community members delivering groceries to older adults, patrons supporting Black-owned businesses, and particularly the determined students in elementary schools and colleges who are continuing their studies virtually.

“We know that roses do grow in concrete, to quote Tupac Shakur,” she said. “Black families are roses growing in the midst of concrete.”