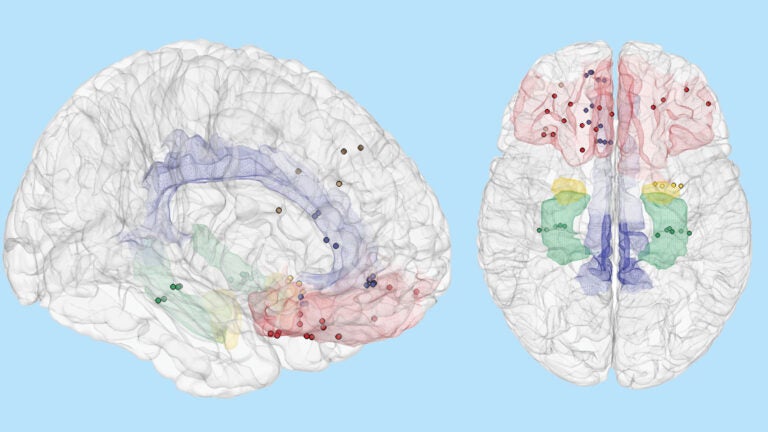

Mood is represented across multiple sites in the brain rather than localized regions, which makes decoding them a computational challenge, according to a USC expert. (Image/Sani et. al., Nature Biotechnology, modified from original format)

Breakthrough brain research could yield new treatments for depression

Findings may yield new therapies for depression and anxiety among millions of patients

Engineers and physicians at USC and the University of California, San Francisco have discovered how mood variations can be translated, or decoded, from neural signals in a person’s brain — a process that has not been demonstrated before.

The study, published in Nature Biotechnology, is a key step toward creating new treatments for depression and other disorders, including therapies that use brain stimulation to treat mood and anxiety disorders in millions of patients who do not respond to current treatments.

USC Viterbi School of Engineering Assistant Professor Maryam Shanechi led the development of the decoding technology. Edward Chang, UCSF professor of neurological surgery, led the human implantation and data collection effort.

According to Shanechi, for clinical practitioners, a powerful decoding tool would provide the means to clearly delineate, in real time, the network of brain regions that support emotional behavior.

Our goal is to create a technology that helps clinicians obtain a more accurate map of what is happening in a depressed brain at a particular moment in time.

Maryam Shanechi

“Our goal is to create a technology that helps clinicians obtain a more accurate map of what is happening in a depressed brain at a particular moment in time and a way to understand what the brain signal is telling us about mood. This will allow us to obtain a more objective assessment of mood over time to guide the course of treatment for a given patient,” Shanechi said.

“For example, if we know the mood at a given time, we can use it to decide whether or how electrical stimulation should be delivered to the brain at that moment to regulate unhealthy, debilitating extremes of emotion.”

The team recruited seven volunteers among a group of epilepsy patients who already had intracranial electrodes inserted in their brain for standard clinical monitoring to locate their seizures. Large-scale brain signals were recorded from these electrodes in the volunteers across multiple days at UCSF while they also intermittently reported their moods using a questionnaire.

Shanechi and students Omid Sani and Yuxiao Yang used the data to develop a novel decoding technology that could predict mood variations over time from the brain signals in each human subject.

“Mood is represented across multiple sites in the brain rather than localized regions, thus decoding mood presents a unique computational challenge,” said Shanechi, holder of the Viterbi Early Career Chair at the Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical Engineering. “This challenge is made more difficult by the fact that we don’t have a full understanding of how these regions coordinate their activity to encode mood and that mood is inherently difficult to assess.”

To find new treatments for depression, developing new methodologies

To solve this challenge, the team had to develop new decoding methodologies that incorporate neural signals from distributed brain sites while dealing with infrequent opportunities to measure moods, Shanechi said.

To build the decoder, the team analyzed brain signals that were recorded from intracranial electrodes in the seven volunteers. Raw brain signals were continuously recorded across distributed brain regions while the patients self-reported their moods through a tablet-based questionnaire.

In each of the 24 questions, the patient was asked to “rate how you feel now” by tapping one of seven buttons on a continuum between a pair of negative and positive mood state descriptors (for example, “depressed” or “happy”). A higher score corresponded to a more positive mood state.

Using their methodology, the researchers were able to uncover the patterns of brain signals that matched the self-reported moods. They then used this knowledge to build a decoder that would independently recognize the patterns of signals corresponding to a certain mood. Once the decoder was built, it measured the brain signals alone to predict mood variations in each patient over multiple days.

New treatments for depression and mood disorders?

The USC/UCSF team believes the findings could support the development of new brain stimulation therapies for mood and anxiety disorders.

Data from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that 16.2 million adults in the United States — approximately 6.7 percent of all U.S. adults — have suffered at least one major depressive episode. Treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can be effective in some but not all patients.

According to the National Institutes of Health-funded STAR*D trial — the longest study to evaluate depression treatments — almost 33 percent of major depression patients do not respond to treatment (more than 5.3 million people in the U.S. alone). In June, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that suicide is on the rise across the country.

For the millions of treatment-resistant patients, alternative therapies may be effective. For example, human imaging studies using positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging have suggested that several brain regions mediate depression, and thus brain stimulation therapies in which a mood-relevant region is electrically stimulated may be applied to alleviate depressive symptoms. While open-loop brain stimulation treatments hold some promise, a more precise, effective therapy could require a closed-loop approach in which an objective tracking of mood over time guides how stimulation is delivered.

Potential for personalized therapies, new treatments for depression

The technology opens the possibility of new personalized therapies for neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety for millions who are not responsive to traditional treatments, Shanechi noted.

The new decoding technology, Shanechi explained, could also be extended to develop closed-loop systems for other neuropsychiatric conditions such as chronic pain, addiction or post-traumatic stress disorder whose neural correlates are again not anatomically localized, but rather span a distributed network of brain regions, and whose behavioral assessment is difficult and thus not frequently available.

The research was partially funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-14-2-0043, issued by the Army Research Office contracting office in support of DARPA’s SUBNETS program. The views, opinions and/or findings expressed are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.