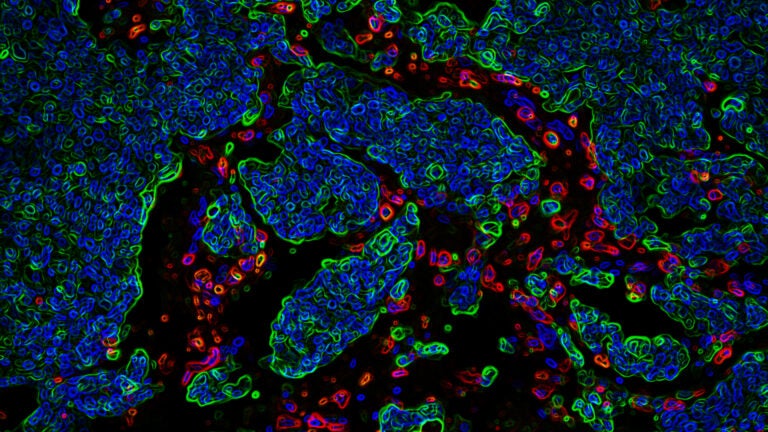

Development of brain metastasis is a complex process in which metastatic cells (green) overcome the protective effect of immune cells (red). (Image/Yu Lab, USC Stem Cell)

Research reveals why breast cancer spreads to the brain

USC researchers have determined how cancer cells target certain organs, which could help develop treatments to slow or stop the disease from spreading.

Most cancers kill because tumor cells spread beyond the primary site to invade other organs. Now, a USC study of brain-invading breast cancer cells circulating in the blood reveals they have a molecular signature indicating specific organ preferences.

The findings, which appear in Cancer Discovery, help explain how tumor cells in the blood target a particular organ and may enable the development of treatments to prevent the spread of cancers, known as metastasis.

In this study, Min Yu, the Richard N. Merkin assistant professor of stem cell and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, isolated breast cancer cells from the blood of breast cancer patients with metastatic tumors. Using a technique she developed previously, she expanded or grew the cells in the lab, creating a supply of material to work with.

Analyzing the tumor cells in animal models, Yu’s lab identified regulator genes and proteins within the cells that apparently directed the cancer’s spread to the brain. To test this concept, human tumor cells were injected into the bloodstream of animal models. As predicted, the cells migrated to the brain. Additional analysis of cells from one patient’s tumor predicted that the cells would later spread to the patient’s brain — and they did.

Yu also discovered that a protein on the surface of brain-targeting tumor cells helps them to breach the blood-brain barrier and lodge in brain tissue, while another protein inside the cells shield them from the brain’s immune response, enabling them to grow there.

“We can imagine someday using the information carried by circulating tumor cells to improve the detection, monitoring and treatment of the spreading cancers,” Yu said. “A future therapeutic goal is to develop drugs that get rid of circulating tumor cells or target those molecular signatures to prevent the spread of cancer.”

Yu is a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC, and her laboratory is located in the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In addition to Yu, other authors of the study are Remi Klotz, Amal Thomas, Teng Teng, Sung Min Han, Oihana Iriondo, Lin Li, Alan Wang, Negeen Izadian, Matthew MacKay, Byoung-San Moon, Kevin J. Liu, Sathish Kumar Ganesan, Grace Lee, Diane S. Kang, Michael F. Press, Wange Lu, Janice Lu, Bodour Salhia and Frank Attenello, all of the Keck School of Medicine; Sara Restrepo-Vassalli, James Hicks and Andrew D. Smith of USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences; and Charlotte S. Walmsley, Christopher Pinto, Dejan Juric and Aditya Bardia of Massachusetts General Hospital.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DP2 CA206653) the Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Foundation, the Stop Cancer Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Alexander & Margaret Stewart Trust, the SC CTSI pilot grant (UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130), a California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) postdoctoral fellowship and a CIRM Bridges award (EDUC2-08381), the National Cancer Institute (P30CA014089) and the Merkin Family Foundation.