From left: USC professors Drew Casper, Todd Boyd, John Walsh and Tatiana Akishina. (Photos by Gus Ruelas)

Legendary USC Professors Are Anything But Textbook

Great professors have the power to inspire, inform, enrich or incite—sometimes all at once.

On the last day of class, Gene Bickers kicks off his shoes on Trousdale Parkway and struts across a trail of burning coals. He’s been performing this feat before his students for 20 years. What better way, after all, to illustrate the dynamics of heat transfer?

Affectionately nicknamed Professor Firewalker, the USC physicist starts by tossing a paper onto the glowing embers. The sheet instantly catches flame.

Next, Bickers wets down his bare feet and draws a deep breath. He takes six quick steps across the fiery path laid out on cinderblocks and hops to safety, to the oohs and aahs of his Trojan undergrads. Passersby stop and stare.

As Bickers soaks his feet in cold water afterward, some students invariably ask if they can give it a try. “‘No. No you can’t!’” he says.

How does he do it? “There’s really no trick to it,” he says. Different materials conduct heat at different rates. As anyone who has grasped the handle of a hot frying pan can attest, wooden handles won’t instantly sizzle your skin like metal. And during the fire walk, Bickers’ feet aren’t in contact with the wood coals long enough to burn.

Professor Firewalker’s feet tingle for an hour afterward. A few times, he ended up with blisters. Uncomfortable, yes, but a small price to pay for an unforgettable physics lesson.

It’s impossible to define a great teacher, but Bickers surely qualifies.

Mesmerizing performer, knowledgeable field guide, trusted mentor, trailblazing innovator—master professors come in many flavors. More often than not, two or three flavors mix in an inspirational mélange. What all great educators have in common is an uncanny ability to engage young minds, and a burning need to ignite intellectual fires.

Fine universities are perhaps best known for their research, but the teaching mission is equally important. It’s a big part of the value students expect from a place like USC.

One of the highest accolades a professor can earn at USC is the Associates Award for Excellence in Teaching. Only two are awarded each year; Bickers won his in 1999. Another hallmark of a great USC professor is fellowship in the Center for Excellence in Teaching (CET). Founded in 1996, this peer-run faculty development organization hosts a bulging calendar of workshops spreading the collective wisdom of standout teachers across the university. The honors lift up and recognize the many men and women who are dedicated to the power of teaching at USC.

Read on for a celebration of a few of the finest.

A force for physics

Demonstrations in college physics classes are common, but “USC is known for having spectacular ones,” says Stephan Haas, chairman of the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Gene Bickers gets a lot of the credit for that.

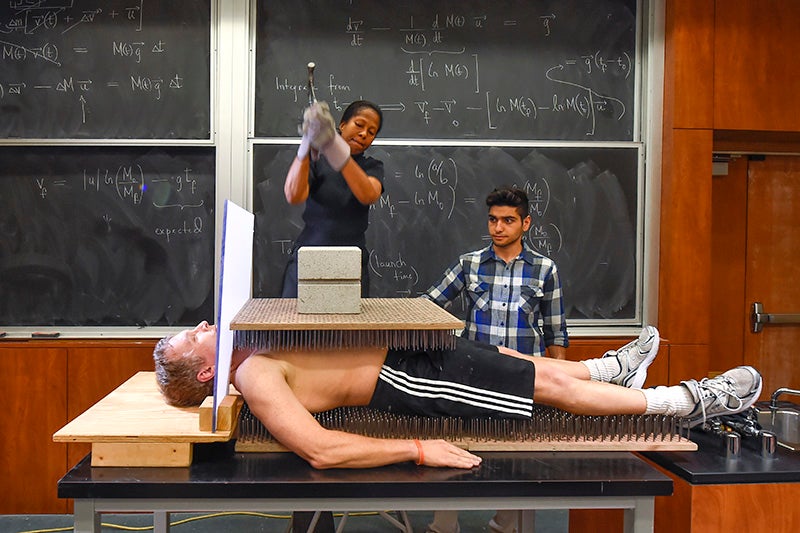

His annual fire walk is one of more than 400 demonstrations on the department’s playlist. Another perennial crowd-pleaser is the bed of nails. In this show-stopper, Bickers lies unharmed between two pallets studded with roofing nails (illustrating the principle that greater surface area equals less pressure). To drive home a related point about damping, the top pallet is weighted down by a cinderblock, which an assistant crushes with a sledgehammer.

For a lesson on the properties of liquid nitrogen, Bickers takes a sip of the freezing stuff and blows out a spectacular condensation cloud (the warmth of his mouth briefly creates a protective vapor layer). An apple soaked in the same liquid nitrogen, however, shatters as it hits the ground.

When he used to teach the general education class Physics 100, Bickers would take students to an amusement park and have them perform experiments on the rides: During the free-fall ride, drop a coin and watch it float; on the roller coaster, observe changes in your apparent weight at the top and bottom of hills; on the spinning Tilt-a-Whirl rides, notice how friction counteracts weight thanks to centripetal forces.

Through teaching, Bickers re-experiences the joy of discovery, and occasionally sees his students get into the act. There was the time Andrew Horning ’08 challenged Bickers to try skydiving. The resulting video is now part of his lecture on the mechanics of terminal velocity. Another student, an expert pilot, once took Bickers up in an aerobatic plane and performed stunts, including a terrifying power dive over the ocean.

“I’ve done a little bit of everything over the years,” Bickers says. “It’s been fun.”

Bickers has spent his entire career at USC, joining the faculty in 1988. Since 2005, he has worn a second hat as vice provost for undergraduate programs. Even as a senior administrator, he still teaches three or four courses a year, all at the introductory level.

His students literally follow him to the Office of the Provost. “There are always a few of them doing homework in the front office,” says Haas, who is himself a 2010 winner of the Associates Award for Excellence in Teaching. “They hang out there. They feel drawn to him. It’s pretty unique.”

Unpacking puzzles

Bickers’ boss, neuroscientist and USC Provost Michael Quick, is also known for his demos. When he taught an “Introduction to Neurobiology” course, students’ jaws dropped when he’d dip his hand in a dish of burning alcohol and calmly report his changing sensations over five excruciating seconds—from wet to hot to ouch! The point: to illustrate the different conduction speeds of various kinds of sensory nerve fibers. The larger the diameter of the fiber, Quick explains in his signature deadpan style, the faster its message reaches the brain. Touch sensation races across the thickest nerve fibers. Medium-sized fibers relay temperature signals a little slower. Pain travels the slowest via slender nerve fibers.

Quick, who has been a senior administrator since 2005, no longer teaches introductory neurobiology, but every spring he still teaches Biology 423, “Epilepsy to Ecstasy.” Neuroscience majors consider the advanced elective the “cherry on top” of their USC education. The case study-based seminar feels like an episode of House. Like TV’s sleuthing doctor, the neuroscience students study a fictional patient’s symptoms, form hypotheses and systematically rule out possible diagnoses.

“Each class we’d walk in and it was a new puzzle that we had to figure out,” says neuroscience major Gwen Holst, a senior who took the class in 2014. “It teaches you how to think critically, and does so in a very fun and engaging way. His wit and dry sense of humor makes for an incredible class experience.”

As the semester progresses, the clinical puzzles get increasingly exotic. In a neural mapping drill called “The Lesion Game,” Quick will tell a student: “You can’t feel any pain in your right arm, and you can’t move your upper torso.” The class orders hypothetical tests—check the patient’s Babinski reflex, for example—until they successfully locate the affected neural pathway.

“The best teachers never ‘teach’ anything to a student,” Quick says about his unorthodox style. “What they do is inspire students enough that they teach themselves.”

Former CET director Danielle Mihram concurs. “I think this is one of the stellar marks of a professor: to encourage the ‘exits off the freeway,’ explore the many areas, and then come back on course. In so doing, the student’s understanding is vastly enriched,” says the university librarian and French professor who specializes in the assessment of learning at the college level. “Michael is willing to let the student’s curiosity take over.”

“The best teachers never ‘teach’ anything to a student. What they do is inspire students enough that they teach themselves.”

Michael Quick

USC Provost

Two years after taking “Epilepsy to Ecstasy,” Holst retains much of what she learned in Quick’s class. A while ago, she saw a Facebook post about a friend’s worrying eye condition: coppery discoloration on the edge of the cornea. Holst commented on the thread: “Have you been tested for Wilson’s disease?”

Stunned, the woman confirmed that her doctor had just ordered tests for the rare inherited disorder. Holst had nailed it.

A gateway to new worlds

Great teachers give students the confidence to go out on a limb. Tatiana Akishina knows all about that. She’s been pushing Russian language students out of the nest for 35 years. A teaching professor at USC Dornsife, she received the 2011 Associates Award for Excellence in Teaching—the first non-tenure-track faculty member to win the prize.

Akishina is an expert in how language is best taught and learned. She has designed several innovative programs at USC and has a knack for finding ways to make students take risks and turn failure into teachable moments.

Over spring break, she takes students to Russia and puts them on a three-day train ride to Siberia, placing pairs of USC students in “kupes”—four-person sleeper compartments—shared with two Russian-speaking strangers.

Students describe the Trans-Siberian Railway journey as life changing. A lot of preparation leads up to that moment: Akishina has to teach them Russian first. “But it’s going that extra step, having classroom work bear fruit for the student in the real world, that marks the great teacher,” says CET director Ed Finegan.

Akishina, who is a CET faculty fellow this year, has measured the impact of such real-world experiences. Using pre- and post-tests, she found that her students retain nearly all the knowledge presented in lectures leading up to the rail trip—far more than they would in an ordinary course.

In 2014, her Siberian exchange class had to forgo the long train ride to Lake Baikal. The Ukrainian crisis was at full boil and a Moscow railway agent refused to honor the American group’s tickets. As Akishina hustled to book last-minute plane reservations and lodging for 20 stranded Trojans, she braced herself for their disappointment. Instead, she found her students energized. Never before had Akishina encountered such “eagerness to learn, alertness to everything around, ability to see and need to debrief every day.”

Getting students out of their routine, whether positive or negative, ramps up learning, she says. “These outside-of-classroom experiences are very important for the general development of our students.”

A stage for learning

Perhaps the most widely recognized style of great professor is the charismatic performer. Drew Casper PhD ’73 and Todd Boyd, both legends at the USC School of Cinematic Arts, are fine examples.

In some ways, they couldn’t be more different. Casper, who holds the Alma and Alfred Hitchcock Endowed Chair, is a film historian and authority on Hollywood from World War II to the 1970s. He’s also a former Jesuit priest. For Casper, the secret to inspired teaching is a passion for one’s subject matter—in his case, movies. “Love is always honest, isn’t it? Further, being honest is the only guarantee of originality,” he says.

Boyd is a sharp-tongued culture critic with tight connections to the African-American entertainment, sports and music scenes. A hip-hop celebrity in his own right, he holds the Katherine and Frank Price Endowed Chair for the Study of Race and Popular Culture, but goes by the handle “Notorious PhD.” Boyd’s lecture style blends street slang with critical theory. “I don’t see myself as a teacher,” he says. “I am a professor. There is a difference. I don’t teach, I profess.”

Despite their differences, Boyd and Casper have much in common as educators.

“They both love to be in front of students and to ‘perform’ their teaching in large classrooms,” says Akira Mizuta Lippit, the school’s vice dean of faculty and a professor in the Bryan Singer Division of Cinema and Media Studies, where Boyd and Casper are based.

Both Boyd’s and Casper’s wildly popular introductory classes fill the 330-seat Norris Cinema Theatre to capacity. Somehow both men can turn an auditorium into an intimate space where it’s impossible to be a passive spectator.

Boyd’s style is confrontational. “He’s somebody who’ll get in your face, agitate and provoke you to respond, to argue, to think and rethink what you believe,” Lippit says. “After a while, the students realize this is part of his pedagogy, and that he will let them argue back.” Boyd teaches a popular freshman course, “Race, Class and Gender in American Film,” and upper-division courses with names like “The Birth of the Cool” or “The Gangster in American Culture,” as well as the graduate course “Reagan’s America (Crack Nation).”

Casper has his own trick for shrinking a large class: He learns every student’s name, and calls them out without warning. (For his blockbuster course “Intro to Film,” offered twice last semester, he memorized 661 names). Students squirm as he paces the aisles and picks out people to answer questions, act out a scene or sing a verse from the musical they’re studying.

Despite such anxiety-inducing tactics, Boyd and Casper inspire intense admiration in their acolytes. Each received the Associates Award for Excellence in Teaching. Michael Bitar ’14 took five courses with Casper. “Some kids at SCA should just say, ‘I majored in Casper,’” jokes the critical studies major, now an assistant and story editor at Sony Screen Gems.

The professors command the respect of the film industry, Lippit notes. Boyd doesn’t just talk about celebrity culture and media: He brings in guests like Grammy-winning jazz artist Branford Marsalis, NBA Hall of Famer Joe Dumars and Oscar-winning filmmaker Oliver Stone. And whenever Casper teaches “The Spielberg Style” or “The Star Wars Phenomenon,” Steven Spielberg and George Lucas will drop in for a Q & A with the class.

An ageless approach

In the digital age, you can’t talk about great professors without mentioning technological innovation. USC Davis School of Gerontology associate professor John Walsh is a maverick in this arena.

A pioneer in Web-based teaching, his latest National Science Foundation-funded innovation is the Root digital learning environment. This free shareware reimagines how students acquire knowledge—incorporating social media and game psychology, along with multimedia videos and animations, electronic labs, interactive boards, real-time quizzes and other tools pushing the educational envelope.

“I use Root to teach courses on cancer and neuroscience, not that it matters,” Walsh says. “Anyone could use Root to teach any course in any subject. It’s a really easy way to create a neat digital classroom for everyone.”

Before winning the 2013 Associates Award for Excellence in Teaching, he received the 2008 Provost’s Prize for Teaching With Technology.

Yet Walsh’s tech-fueled teaching couldn’t be more human. “Lectures should touch a raw nerve where you laugh and cry together,” he says. “Emotional learning has more meaning and it is lasting.”

Josh Faskowitz ’14 took Walsh’s “The Neurobiology of Aging” course his senior year. Built around Walsh’s innovative neuroscience shareware, the course put students in charge of the website, turning each into a “mini-expert on their part of the curriculum,” says Faskowitz, now a staff scientist at the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute.

Class meetings became lively discussions peppered with peer-to-peer teaching. Outside class, Walsh would invite students to comment on new papers he posted. The site became a bustling intellectual hub where students would take positions and link to articles supporting their arguments.

For all of Walsh’s technical expertise, there’s a youthful, laid-back quality that catches students by surprise. “It’s a joy to be in his class because of his relaxed, down-to-earth personality,” says Faskowitz, who will begin doctoral studies in neuroscience this fall. “He would talk about surfing, and then he would spew out all this neurobiology. It was a cool contrast.”

USC Davis Dean Pinchas Cohen sums it up best: “John Walsh manages to be that extremely rare combination: a world-class scientist as well as a world-class teacher.”

A 2008 video pays homage to his free spirit. In it, Walsh expounds on the joys of teaching: “Being a professor—it’s the best job in the world,” he says. “I wake up and I’m back in college again. I feel like Peter Pan. I never get old.”