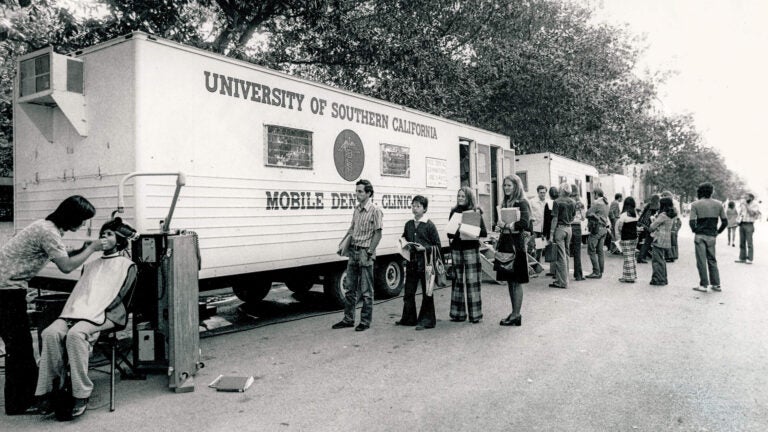

For the past 50 years, the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC has combined dental care with social services to address the oral health needs of L.A. communities holistically through mobile dental clinics, health fairs, screenings and educational programs. (USC Photo/University Archives)

Community-powered care

USC researchers and clinicians are caring for — and collaborating with — local communities to develop innovative treatments for complex diseases.

In January 2021, Dodger Stadium was one of California’s largest COVID-19 vaccination sites, dispensing vaccines to up to 12,000 people daily.

Cars lined up throughout the stadium parking lot as volunteers and staff from USC, the Los Angeles Fire Department and the nonprofit Community Organized Relief Effort prepped doses for L.A. residents.

Throughout the pandemic, the USC Alfred E. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences partnered with Keck Medicine of USC, the Keck School of Medicine of USC, other health-related USC entities and L.A. city and county officials to spearhead a massive, multidisciplinary COVID-19 response that went far beyond Dodger Stadium — establishing mobile clinics, making door-to-door visits, busing patients to vaccination centers and hiring community vaccine facilitators.

The collaborative effort highlighted the university’s role in building local connections and championing the health and well-being of its adjacent communities. “Everyone stepped up,” says Vassilios Papadopoulos, dean of USC Mann.

“Everyone shared the same mission of getting the vaccines out into the community.” Richard Dang, an assistant professor of clinical pharmacy and assistant director of the residency programs at USC Mann, helped lead mass vaccination efforts throughout the city. “At the time, USC was recognized as the institution providing this moment of hope,” Dang says.

Despite the unprecedented scale of the pandemic, Dang adds that USC Mann is accustomed to being a good neighbor to local communities, frequently organizing free health education and screening programs. “We also provide free access to tests for diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure, and distribute Naloxone for opioid overdoses,” he says.

After all, the good health of its neighbors is an essential metric of success for USC’s health sciences schools and its medical enterprise (which includes Keck Medicine of USC’s four hospitals and more than 100 clinics).

The university’s constellation of health sciences schools demonstrates just how far that health extends beyond the hospitals: They include the USC Alfred E. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; the USC Mrs. T.H. Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy; the USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy; the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC; the Keck School of Medicine of USC; the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology; and the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

Trojans as good neighbors

USC’s community-based work includes a consortium of scientists, researchers and clinicians committed to tackling health disparities and making a visible, positive impact on the neighborhoods surrounding the University Park and Health Sciences campuses by providing access to high-quality medical and social services.

“We’re always thinking about how we can bring all our expertise and work with the community to improve the health of our neighbors,” says Rodney B. Hanners, CEO of Keck Medicine of USC, the university’s health system.

At Ostrow School, oral health initiatives combine dental care with social services. At the Keck School of Medicine, a street medicine program seeks to reach the county’s unhoused population. USC Leonard Davis faculty and graduate students use advocacy and research to illuminate the gaping holes in our social safety net for elder care.

This ongoing relationship with local communities is mutually beneficial: Patients receive highly specialized care from the academic health system and have the opportunity to engage with health science practitioners through research, clinical trials and more.

Community members that choose to participate in USC studies contribute to more comprehensive and applicable insights that researchers and clinicians can use to inform patient care and drive innovation. Varied in their ethnicity, housing status, complexity of disease and other metrics, their participation leads to a better understanding of all communities. This kind of translational research has the power to transform basic discoveries into treatment directly beneficial to patients suffering from complex diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease or cancer.

Prioritizing access to care

While innovation and evidence-based care form two pillars of USC’s community-oriented health care philosophy, accessibility is an important third pillar.

“The most significant driver of health disparities is access to health care,” says Raffi Svadjian, PharmD/MBA ’03, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at USC Mann.

Since 2017, Svadjian has served as USC’s executive director of community pharmacies, supervising the three pharmacies operated by USC Mann: one on the University Park Campus, one on the Health Sciences Campus and one next to USC Verdugo Hills Hospital.

The school-operated pharmacies are an essential resource for both the USC community and those living around the university’s campuses and health facilities who would otherwise have few points of access to health care. Svadjian and his colleagues at USC Mann emphasize the power that pharmacists have to address health care access issues in under-resourced populations as first-line health care providers who are essential fixtures in communities.

Bringing the pharmacy to the community

The issue of access also informs USC Mann’s decision-making and civic engagement. In 2017, Papadopoulos approached Svadjian about opening a new pharmacy in South Los Angeles after pharmacy alumni highlighted the significant need in the area. Svadjian and his team surveyed more than 10 potential sites, guided by research from colleague Dima M. Qato, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy and spatial sciences and a leading researcher in pharmacy access. Qato most recently developed an interactive tool to map “pharmacy deserts” and determined that 25% of neighborhoods lack reliable access to pharmacies.

The team settled on a location next to where a Rite Aid had recently closed. Svadjian says the South L.A. pharmacy — which aims to open next year — represents a long-term commitment to the community, going beyond shorter engagements such as health fairs and workshops.

He hopes the new pharmacy’s impact will extend beyond dispensing prescriptions: His goal is to increase health education in the community while also providing an avenue for USC Mann students to learn from and interact with their neighbors.

“Obviously, one pharmacy is not going to change the world, but we have to start somewhere,” Svadjian says. He explains that by establishing a new pharmacy in a community that large corporations such as Rite Aid and CVS have avoided or left, the project furthers the university’s efforts to be a “good neighbor” to the communities surrounding its campuses and health facilities.

Letting the community fuel the research

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, a Distinguished Professor of Population and Public Health Science at the Keck School of Medicine, also believes that addressing access to care is key when tackling health disparities.

Her collaborative approach to community health closely aligns with USC President Carol Folt’s Health Sciences 3.0 “moonshot”: She leads teams on community engagement within the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, the Southern California Center for Latino Health, the Center for Health Equity in the Americas, the Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, and other health institutes in Southern California to efficiently translate academic research into health care treatments, public health practice and policy. She also works with more than 100 USC faculty and over 190 community partners to transform community research into solutions that address the entire spectrum of disease prevention.

“It typically takes eight to 10 years for scientific discoveries and advances in medicine to make it out into the community,” says Baezconde-Garbanati, “but we’re really trying to accelerate that so people can live longer and healthier lives.”

She also works with the All of Us research initiative via the National Alliance for Hispanic Health to encourage community participation in research and clinical trials. She argues that in the age of artificial intelligence in health care, it is “especially urgent” for the needs and data of traditionally underrepresented communities to be reflected in emerging databases.

“USC is an anchoring institution in community health care, and we’re developing various ways to further engage with our neighbors so we can develop great innovation and amazing discoveries together with our community partners,” Baezconde-Garbanati says. “I feel like it’s a renaissance moment at USC, and I’m very proud to be part of that.”

Inclusion as a strength

In an effort to build a more equitable, culturally competent and compassionate health care system, the Keck School of Medicine also partners with the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences for a master’s program in narrative medicine that brings health professionals into local communities to better understand the importance of storytelling for individuals, community wellness and the health care system.

One of only two such programs in the country, students in the program — often from the creative writing or medical fields — have workshop opportunities to teach and learn from community partners in topics such as strategies for challenging the hierarchy between patient and clinician.

This year, Keck Medicine of USC hospitals and USC Student Health earned an LGBTQ+ Healthcare Equality Leader designation from the Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s 2024 Healthcare Equality Index (HEI) survey. The survey found that Keck Medicine of USC — which is earning the distinction for the seventh time in recent years and includes Keck Hospital of USC, the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, and community hospitals USC Verdugo Hills Hospital and USC Arcadia Hospital — deserved a top score due to its health care facility policies and practices that are dedicated to the equitable treatment and inclusion of LGBTQ+ patients, visitors and employees.

The USC Gender-Affirming Care Program embodies this commitment by featuring a centralized program with specialists and staff who tailor comprehensive health care to transgender, nonbinary and gender-diverse patients.

This includes individualizing patients’ health needs based on their personal goals, which could include hormone therapies and surgical interventions, but also routine care such as preventative medicine and mental health care.

Program leaders developed early partnerships with community organizations such as The TransLatin@ Coalition, one of the largest trans-led nonprofit organizations in the country, to ensure that community members have a say in solidifying the program’s vision. USC clinicians and staff also host regular bilingual focus groups both at USC facilities and at The TransLatin@ Coalition’s headquarters in Koreatown to continue to promote mutual listening between the health system and the community.

Meeting people where they’re at

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that sometimes, health care workers have to serve their communities even when face-to-face interaction isn’t possible.

Prior to the pandemic, the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work’s telebehavioral health program was fairly small, with graduate students providing online mental health counseling to a mostly migrant worker population through a contract with Monterey County. Students also provided some pro bono services to local residents in L.A.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the school was able to pivot and rapidly expand its online services and provide remote practicum opportunities for its graduate students who could no longer practice in person.

“There was this huge mental health need, with people dealing with the stresses related to COVID-19, such as grief and health issues,” says Professor Ruth Supranovich, associate dean of community and clinical programs at the school. “We were able to respond both to the need for the students, but also to the need in the community.”

Since that initial expansion, the program has partnered with CALHOPE, a crisis counseling assistance and training program that receives funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and is run by the California Department of Health Care Services to provide crisis support and counseling to the entire state. Through CALHOPE@USC, USC’s Telebehavioral Health Clinic — which opened in 2012 — provides inclusive individual and group counseling to anyone age 12 and older who lives in California. Services are free to the public and designed to be short term — the limit is six sessions per person.

Beyond short-term counseling, the clinic also connects community members to longer-range resources such as food assistance, mental health services, housing assistance and other forms of support.

The school also applied for and received funding from the California Victims Compensation Board to open a trauma recovery center for victims of violent crime. With the funding, USC therapists — including many graduate students and graduates of the master’s in social work program — provide evidence-based mental health treatment for trauma along with case management.

In addition to referrals from nonprofits, legal offices and word of mouth, the program receives client referrals from Keck Medicine of USC, USC’s occupational and physical therapy programs, the USC Department of Public Safety, and L.A. General Medical Center’s Hospital Violence Intervention and Prevention program.

With Trojans of all disciplines engaging in community-based initiatives and research, the university is well-poised to help Angelenos live longer, healthier lives.

“The stars are aligned — from the president’s office to our deans and faculty and to our students — in embracing our communities so its members can lead healthier lives,” Baezconde-Garbanati says. “There’s so much that we still need to do, and it really is going to take all of us coming together.”