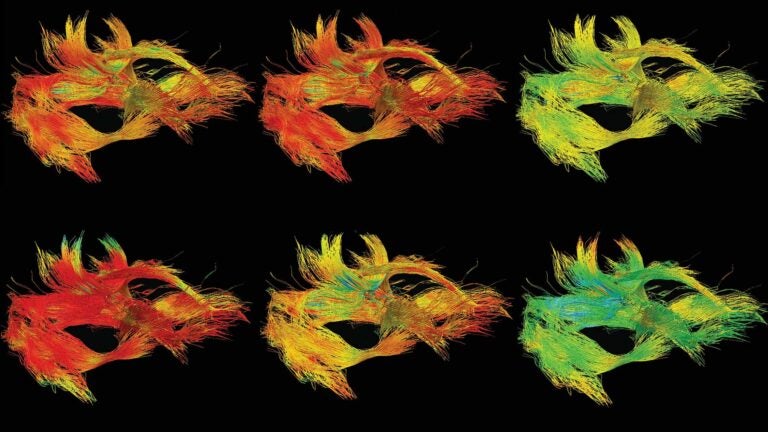

Some children with traumatic brain injury take longer to transfer visual perception information between the brain hemispheres. (Image/Emily Dennis/Neurology, medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology)

Childhood head injuries appear to cause structural changes in brain

The speed of information traveling within a child’s brain may signal who needs the most help after a head injury

Children with delayed visual perception as a result of serious head injuries may end up with structural changes in their brains that interrupt normal development, a Keck School of Medicine of USC study shows.

The USC scientists said the finding is the first step to creating targeted treatments for a subpopulation of children with traumatic brain injuries, the leading cause of disability among the young. The goal is to save their brains from further deterioration as a consequence of an initial hard bump, blow or jolt to the head.

USC researchers and their colleagues examined the brain scans of 21 children in Los Angeles County who fell from skateboards, scooters and bikes or were hit by a car either as a passenger or as a pedestrian. Study participants were 8 to 18 years old when they visited a pediatric intensive care unit for moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Twenty healthy children who had not had a brain injury served as the control group.

“We found that children who had delayed information transfer times between the two brain hemispheres had widespread regions of white matter disorganization and progressive loss of white matter volume,” said Emily Dennis, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral scholar at the Keck School of Medicine. “In children, this disruption to myelin — the insulation that facilitates information transfer — is compounded because the brain is still maturing. Myelination typically continues beyond age 30.”

The preliminary study published on March 15 in Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology, found that children who took more than 18 milliseconds to transfer information between the brain hemispheres did not recover as well from traumatic brain injury compared to their similarly injured counterparts.

More than 55 percent of traumatic brain injuries among children 0 to 14 years of age are caused by falls, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Finding this potential biomarker may help us identify patients who are at risk for a more prolonged recovery.

Emily Dennis

“Finding this potential biomarker may help us identify patients who are at risk for a more prolonged recovery,” said Dennis, a postdoctoral scholar at the Imaging Genetics Center. “If we can identify the children who will take longer to recover from traumatic brain injury, we may be able to develop interventions that can be used after they leave the hospital but before their continued loss of white matter.”

The bridge between the brains

Scientists took diffusion-weighted MRI scans of the young study participants two to five months after their injury and again about a year later. The children took thinking and memory skills tests. They also had electroencephalograms (EEGs) done while they completed a computerized pattern-matching task, enabling researchers to examine how quickly information was transferred from one brain hemisphere to the other.

Researchers tracked brain activity as it transferred information through the hemispheres via the corpus callosum, a bridge resembling a mohawk in the middle of the brain with extensions into both hemispheres.

During the initial evaluation, half of the injured kids had a transfer time of more than 18 milliseconds while the other half were in the normal range between 7 to 10 milliseconds — more than 30 times the speed of the blink of an eye.

About a year later, the group of children whose information transfers took the longest also experienced a loss in white matter and disorganization in the wiring that connects the different regions of the brain. However, the group whose information traveled at a normal speed showed no significant difference from the healthy control group when tested for their memory-processing speed and their ability to control inhibition.

“The slow-transfer group started off with worse white matter integrity and had poorer cognitive function across a range of domains, whether it was on the brain processing speed or self-control,” Dennis said. “The problems get worse as these kids age.”

The normal-transfer group had cognitive test scores slightly lower than the healthy group, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Dennis, a research associate at the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, and her colleagues hope to continue this line of research in a larger, multisite cohort of 450 children. But this time, they also will collect blood samples a week or so after the traumatic brain injury and intermittently thereafter to look for genetic markers and to see if inflammation is causing brain damage.

Inflammation is a necessary and a healthy response to injury, Dennis said, but if it is excessive or lasts too long, it can cause additional damage. Researchers need to investigate if inflammation is the reason for the observed white matter disorganization and loss of myelin that facilitates information transfer, she added.

“This finding clearly needs to be replicated in a wider cohort, but it raises the possibility of a second window for intervention to reduce the long-term functional morbidity of traumatic brain injury in children,” according to the study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, UCLA Brain Injury Research Center, UCLA Steve Tisch BrainSPORT Program, Easton Foundation and the UCLA Staglin IMHRO Center for Cognitive Neuroscience.