El Favorito de USC

Mexican restaurant and L.A. staple El Cholo has been a Trojan favorite for decades — but its relationship with USC involves more than just food.

El Cholo, one of the most revered Mexican restaurants in Los Angeles, celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Over that century, little by little, the University of Southern California became part of the restaurant’s DNA. For evidence, one need only look at the walls.

Along with photos of longtime customers like celebrities Jack Nicholson and Michelle Phillips, there are images of USC’s athletic greats: Paul Salata, hero of the 1945 Rose Bowl; Tom Seaver, a Trojan star in the 1960s before his Hall of Fame pitching career; Cheryl Miller, the basketball legend; and football players Matt Leinart, Reggie Bush, Anthony Davis, Keyshawn Johnson and Petros Papadakis.

An entire room is named after Louis Zamperini, the USC track star who gained fame first as a 1936 Olympic athlete and then for his ordeal after his bomber crashed in the South Pacific during World War II, an episode recounted in the book Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption and its film adaptation. Zamperini later said in a letter that one thing that kept him alive as a prisoner of war was wanting to come home and enjoy a No. 1 combination plate at El Cholo. (That would be the cheese enchilada and the rolled beef taco, with rice and refried beans.)

So, you might think Ron Salisbury, El Cholo’s 90-year-old owner, was a USC fan from an early age. Not so. “I grew up liking UCLA,” he says, “because I was 7 years old listening to radio broadcasts of the football games and decided I’d better choose sides.”

A Century with the Cardinal and Gold

In 1923, as athletes and fans set foot in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for the first time, a more modest establishment — a small Mexican restaurant — opened its doors a few blocks to the east. And like the Coliseum, the restaurant grew to be an institution for generations of USC students.

It was called Sonora Café, in honor of the native state of Rosa and Alejandro Borquez, the Mexican immigrants who founded it. After a couple of years, it was renamed El Cholo, and in 1927 the couple’s daughter and son-in-law — Salisbury’s parents — opened a second location, this one on Western Avenue. In 1931, they moved across the street to a converted bungalow that became the El Cholo flagship. Its inexpensive combination plates drew appreciative diners. Over the years, they increasingly included USC students making the 3-mile hop from campus.

They would come here when they were students, just en masse, tons of USC students.

— Ron Salisbury

As Salisbury spent his formative years in the restaurant — where he learned to count coins in the cash register as a 4-year-old and moved on to washing dishes and ultimately managing — the USC connection was apparent. “They would come here when they were students, just en masse, tons of USC students,” he says in a chat in the Zamperini Room. “Then, of course, after they’d graduate, they would come here before games, after games. Just a huge influx.”

Salisbury went off to college at Brigham Young University, though he did take an economics class at USC during one summer vacation. (“So I could claim I did go to school there,” he jokes.) Upon graduation in 1954, he took over management of the restaurant. In the ensuing decades, he eventually came around to the Cardinal and Gold and developed some lifelong Trojan friends.

Lessons Beyond Food

One was Seaver, who as a major leaguer would stop by El Cholo for lunch while on road trips and bring other players along. (A rookie named Nolan Ryan was introduced by Seaver as “the guy who shines my shoes.”) Another was John Papadakis, a defensive standout in the coach John McKay football era, who went on to a restaurant career of his own. (“We would trade shop talk,” Salisbury says.)

A lasting connection came when George Raveling arrived as USC basketball coach before the 1986-87 season. Salisbury, who followed Raveling’s coaching success at Washington State University and the University of Iowa, read that one reason he had come to USC was that L.A. was a great restaurant town. Salisbury wrote a letter inviting the newcomer to be a guest at El Cholo and offered a list of other restaurants that would be worth a visit. Raveling took him up on it.

“Halfway through lunch, I was already starting to figure out, this guy’s a keeper,” Raveling recalls. “There are not many people I would trust my life with, but Ron would be one of them.” They shared a curiosity about books and travel — trips together to the Italian Riviera and to Mexico City are “indelibly tattooed on my mind,” the coach says. And there was El Cholo itself.

Raveling would take his team there. He would tell out-of-town visitors, “I’m going to take you to what most people in L.A. think is the best Mexican restaurant.” And when Raveling had a serious car accident in 1994 that ended his coaching career, “Ron brought food to the hospital and called other restaurants and had them bring food.” (Raveling says he has tried “about everything” on the El Cholo menu, and always starts with the meatball soup and the nachos.)

I’m going to take you to what most people in L.A. think is the best Mexican restaurant.

— George Raveling

Others from the athletics department found their way to El Cholo as well, including Mike Gillespie, an infielder/outfielder for the Trojan baseball team in the early 1960s who returned as head coach from 1987 to 2006. Gillespie, too, became a close friend of Salisbury. They cooked up a scheme to draw more fans to ballgames at Dedeaux Field on weekends, when students would head home from campus. Salisbury took his staff to the stadium and served up $1 tacos.

“It didn’t work,” he says. “The kids were gone.” But he and Gillespie remained close until the coach’s death in 2020. (Last fall, the Trojan Baseball Alumni and Boosters honored Salisbury with the Arthur C. Bartner Service Award as a longtime supporter and friend of USC baseball.)

One reason Salisbury is drawn to coaches is that they provide a model for his own business. He wants those running his restaurants — the Western Avenue location and several others — to think of themselves not as managers but as coaches. “Coaches are much more focused,” he says. “They produce a better product, because they’re teaching, measuring and making sure [their players] are at their absolute best — that they’re a tight team.”

To that end, he called on another USC friend — former football coach John Robinson — to be a speaker at a 2018 retreat for about 15 senior staff members. Robinson’s most memorable counsel, Salisbury says, was this: “We don’t say, ‘This is the way I want you to do it.’ We say, ‘This is the way we do it at USC.’” The motivational takeaway, Salisbury says, was to make a team feel that “you’re part of a system that we take pride in.”

USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun, the author of To Live and Dine in L.A.: Menus and the Making of the Modern City, says El Cholo is a symbol of continuity — part of an L.A. family dining culture where, whether you were 5 years old or a grandparent, “you could all find something on the menu you liked.”

“Once a year, I get a longing for something comfortable,” Kun says, “and El Cholo is my default setting.”

Growing a Trojan Family

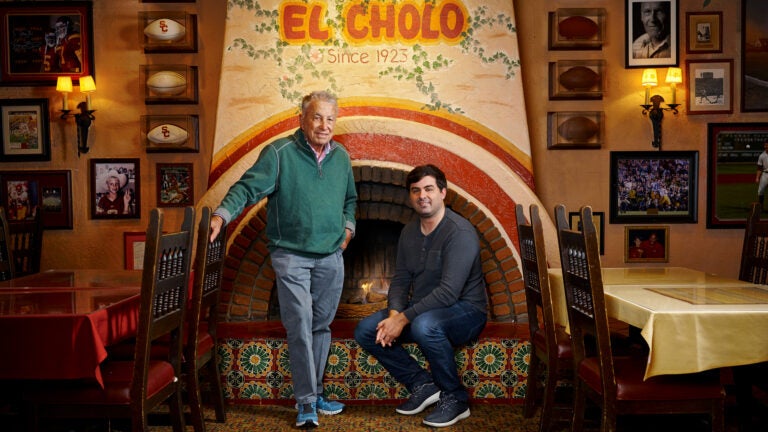

As El Cholo celebrates its 100th anniversary and Salisbury approaches the 70-year mark in his stewardship, the owner still likes to be “moving in fifth gear.” But he is also looking to El Cholo’s future, which will be in the hands of a bona fide Trojan: Brendon Salisbury ’10, the youngest of his seven children.

Brendon, like his father, grew up in the restaurant. He even took violin lessons because he fancied being a mariachi. That dream didn’t pan out, but he felt drawn to the family business. “We couldn’t go to the restaurant and just eat,” he says. “You always had the eye of an owner.” His early experience included work as a busboy, a dishwasher and — at 21 — a back bartender.

He was also, from an early age, drawn to USC. “The university meant a lot to us,” he says. His family went to football and baseball games, and he played touch football on campus. So there was no doubt where he wanted to enroll. He was a history major as an undergraduate and went to Southern Methodist University for a master’s in business administration; he is now El Cholo’s chief financial officer.

“We’re still a small business at heart — we’re a family business,” he says. Beyond finances, he’s involved in all aspects of operations, including a Salt Lake City location opening later this year. “There’s a balance of growing as a business and what people expect of a restaurant, but keeping rooted in the history,” he says. So, the El Cholo menu — which notes when each dish was introduced — will continue to evolve, but fans of the No. 1 combination plate need not fret.

And might El Cholo be around for another 100 years? “That’s the goal,” he says.

Kevin McKenna ’76 is deputy business editor of The New York Times, where he wrote about El Cholo’s history for the Food section in January.