Fast fashion is fueled by a supply chain tainted by human rights abuses and forced labor. (Photo/AdobeStock)

Is fast fashion slowing down? How global trade is being used as a ‘force for good’

Amid U.S.-China tensions, trade regulations and consumer demands have brought human rights into sharp focus. USC experts discuss how the global textile industry is changing.

In the world of fast fashion, where trends are born as quickly as they are discarded, global trade regulations have struggled to keep pace with relentless cycles of production and consumption.

In attempting to meet the demands of this fast-paced sector, global trade has historically failed to address the troubling reality hiding behind the industry’s glamorous façade: a supply chain tainted by human rights abuses and forced labor.

But experts say that’s changing.

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security began enforcing the standards for manufacturing and trade under the Uyghur Forced Labor Protection Act to crack down on Asian goods that U.S. officials suspect are the product of forced labor by imprisoned ethnic minorities. Those include the Uyghurs, whose maltreatment has been extensively documented.

The United States has banned a large number of garment imports from Vietnam, a major exporter of textiles. Companies there were found to be sourcing materials, including cotton, from manufacturers in China that the U.S. government believes violated trade and labor standards.

“We have a calling to use trade as a force for good, advocating for fairness creating real opportunity for all of our people,” said U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai at a “Dean’s Dialogue” with Dean Geoffrey Garrett of the USC Marshall School of Business at Town and Gown on the University Park Campus in May.

“There are substantial challenges in the relationship,” said Tai, referring to the U.S. and China. “The People’s Republic of China’s growth and development over the last few decades have been phenomenal, but the impacts, and especially the negative impacts on other economies — including ours — are having consequences that we cannot ignore.”

Under scrutiny, brands confront the human cost of fast fashion

“The fast fashion industry openly admits to creating disposable products with no apologies. But it’s crucial to include labor in the definition of sustainability because people are an integral part of our environment,” said Annalisa Enrile, a teaching professor of social work at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

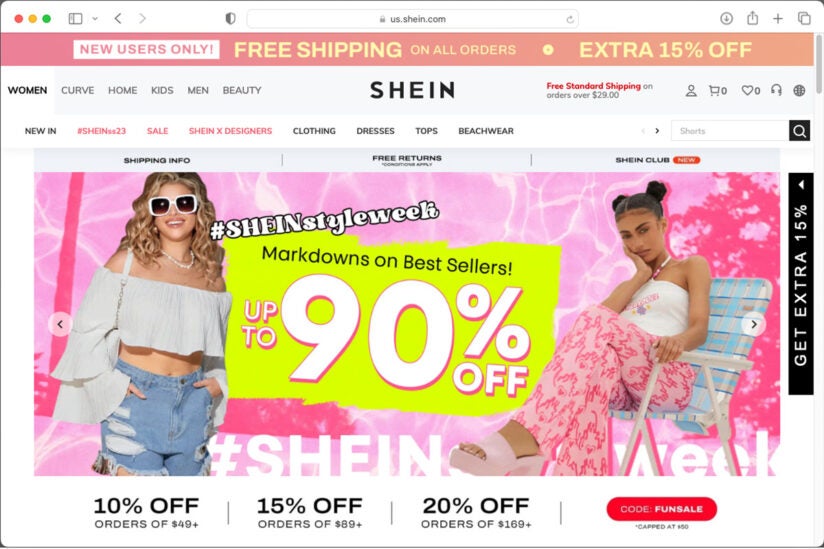

Shein, the world’s largest online fashion retailer, has faced repeated backlash for suspected labor and human rights abuses in its supply chains, particularly the use of materials produced by imprisoned Uyghurs in China’s Xinjiang region. U.S. lawmakers have called for investigations and potential tariffs, further complicating Shein’s rumored plans to go public. The brand has since relocated its headquarters from Nanjing, China, to Singapore and invested in massive PR campaigns — including extravagant influencer factory tours in China — to clean up its image.

Enrile — an expert in global justice, human trafficking and exploitative labor — sheds light on the plight of migrants and child laborers, who constitute a significant portion of the global labor force. The International Labour Organization estimates that there are over 170 million migrant workers worldwide, nearly half of whom are women.

“Anywhere you have large-scale migration, you will also have a higher rate of labor exploitation. These countries often have export processing zones where factories are built with different laws and standards to attract businesses. It’s a massive scope, with thousands of people migrating for labor every day, leading to entire villages in developing countries without women,” Enrile said.

Gender-based violence and harassment in the fashion industry are well-documented, primarily driven by male factory owners and supervisors who enforce unreasonable production targets imposed by fashion brands. Some employers resort to coercive measures, including pressuring female workers to vow to not become pregnant, denying maternity leave and terminating pregnant employees.

Meanwhile, conservative estimates from the International Labour Organization show that South Asia, a major hub for the world’s garment exports, is home to approximately 16.7 million children aged 5-17 engaged in child labor, with 10.3 million falling within the 5-14 age range. Children between the ages of 5 and 11 represent around one-fifth of all child laborers in South Asia.

However, Enrile pointed out that it is difficult to quantify and understand the full extent of child labor globally due to variations in its definition across countries. For example, in Vietnam, the age of employment is 15. In Bangladesh the legal age is technically 14, but children as young as 12 are allowed to engage in loosely defined “light work.”

Empowered consumers drive fashion toward social responsibility

In today’s ever-evolving landscape, the rise of conscious consumerism has become a game-changer. With a heightened awareness of the profound environmental and social consequences of their decisions, consumers are exerting immense pressure on fashion brands to revolutionize their supply and labor practices. The demand is clear: align with sustainability, embrace social responsibility and embody unwavering ethical values.

“The accessibility of information has brought to light the ethical concerns around product sourcing. We’re seeing a preference for not just fair trade, but direct trade and more conscious and socially aware consumerism,” said Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, the James Irvine chair in urban and regional planning and professor of public policy at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

We’re seeing a preference for not just fair trade, but direct trade and more conscious and socially aware consumerism.

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, USC Price

Consumers value the origin of products, showing a preference for goods hailing from regions known for their quality, Currid-Halkett explained. An example of this is the resurgence in American manufacturing, especially the “Made in the USA” movement prominent in high-end denim and loungewear such as T-shirts and sweatshirts.

“It holds great importance for the American economy as it reflects a sense of social consciousness around our purchasing decisions. When a product is made in the USA, made in L.A. or made in Brooklyn, part of its appeal lies in knowing where it comes from and who is making it,” she said.

The trend is gaining traction among a much larger consumer base, she added. While high-income consumers initially had the means to pay for these types of goods, ethically sourced clothing is becoming increasingly more accessible amid growing sensitivity toward climate change and social justice.

“The industry’s pursuit of the best version of a product extends beyond luxury; it encompasses a balance between quality and affordability. This shift in consumer mindset is reshaping our nations’ industries as they seek out the people, countries and places that produce the best versions of various products,” Currid-Halkett said.

The future of fashion — and supply chain transparency — is digital

Companies have already begun leveraging the power of emerging technologies, such as generative AI and mixed reality, to bolster their marketing strategies. Through robust e-commerce platforms, they provide personalized recommendations driven by AI algorithms. virtual reality and augmented reality technologies enable virtual try-ons and immersive shopping experiences.

But this expanding digital toolkit also presents opportunities for enhancing transparency and accountability across even the most complex supply chains.

Nick Vyas, an associate professor at USC Marshall and an expert in global supply chain management, sees great promise in artificial intelligence to revolutionize business processes within the global fashion industry.

Through generative AI, retailers and manufacturers can track inventory using RFID tags and IoT sensors, ensuring better visibility throughout their clothing supply chains. AI-powered decision-making can help companies select suppliers based on their performance, certificates, and historical and real-time data, ensuring ethical sourcing practices.

As we navigate these tumultuous times, the key to resilience lies not in resisting change but in embracing it.

Nick Vyas, USC Marshall

“Beyond the quest for lucrative expansion in new and existing foreign markets, the industry must redefine its success parameters. We must transition from a single bottom-line approach to a triple bottom line that includes profit, people, and the planet,” Vyas said.

“The prevailing economic headwinds should accelerate our investment in emerging technologies that enhance efficiency and promote sustainability. As we navigate these tumultuous times, the key to resilience lies not in resisting change but in embracing it,” he said.

“Change requires a collective commitment to transparency, both in our own actions and in the systems that govern us,” Enrile added. “Just as we have made strides towards environmental sustainability, we must apply the same dedication to human rights.”