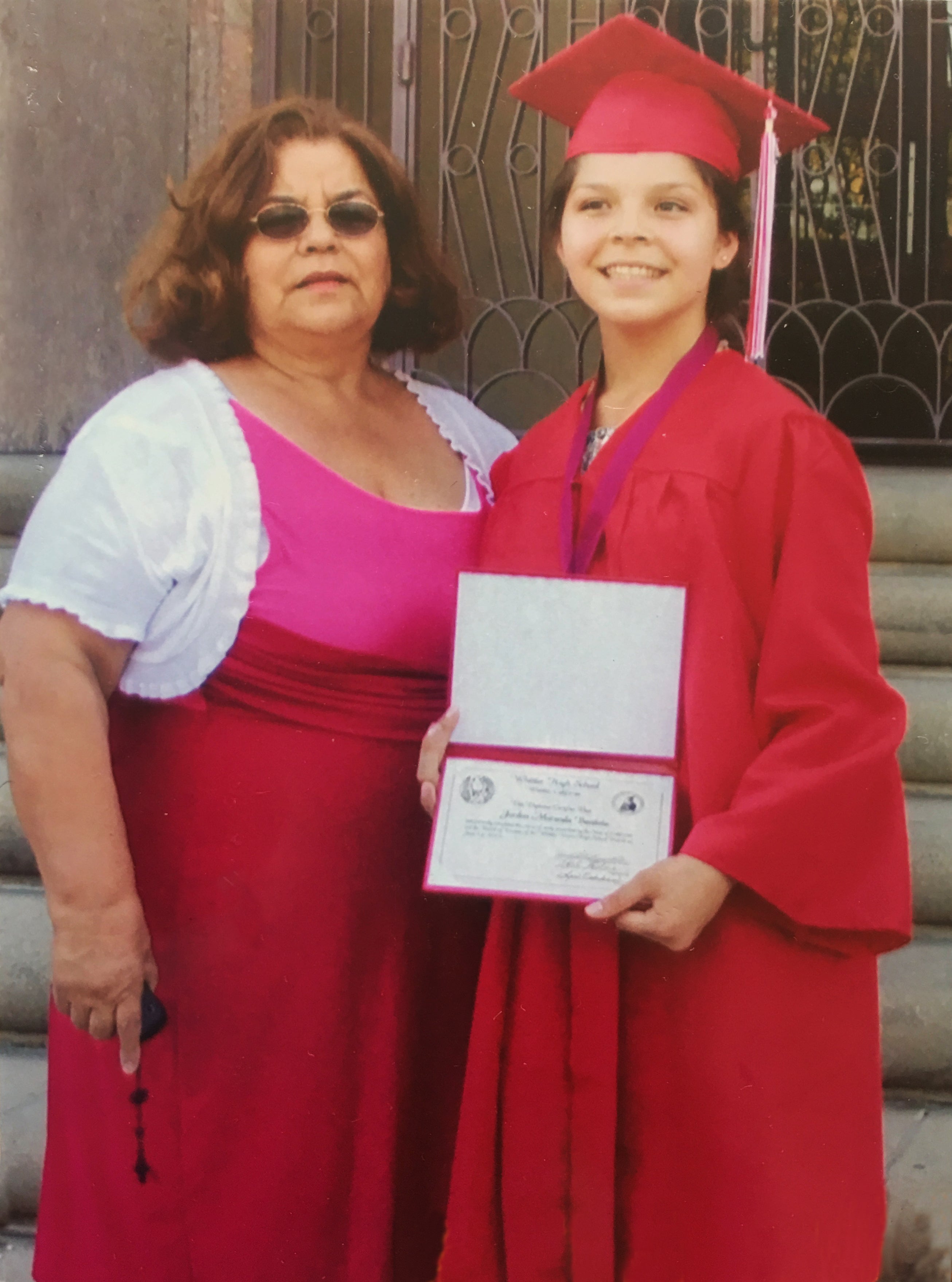

Once unable to walk or even sit upright, Rafael Hernandez now plays baseball. | PHOTO BY DANIEL DRUHORA

For a Boy Locked in His Own Body, These Doctors Brought Hope

Children with dystonia get up and walk again through science, engineering and a brain implant procedure from a team at USC.

Rafael Hernandez shouldn’t be alive—much less playing baseball.

When he was four months old, his parents’ car collided head on with a semi truck. His father was killed on impact, and his mother lifted the boy out of the wreckage, his car seat split in half.

His skull was fractured, and to save his life, doctors removed almost half his brain.

The brain injury spurred what’s called dystonia—a neurological movement disorder that would lock him inside his body, causing involuntary muscle spasms and painful, twisting movements.

“They told me he’ll never learn to sit or walk, feed himself or reach for objects,” says his mother, Mariza Hernandez. “He’d be legally blind and the grand mal seizures would eventually kill him.”

But she refused to believe it.

Today, at 23 years old, Rafael Hernandez dances and sings. He also plays baseball. In August, his mother cheered him on as he pitched in a Little League Intermediate World Series “Challenger Division” game in Sacramento, Calif., for the Azusa Challengers, a team of children and young adults with disabilities.

He survived thanks to his mother, as well as an emerging medical procedure called deep brain stimulation, or DBS. This procedure aims to calm the electrical malfunction in the brain that spurs dystonia.

The longstanding procedure has been re-designed and honed by USC’s Terence “Terry” Sanger—who does triple duty as a physician, engineer and computational scientist—and other researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) and the Keck School of Medicine of USC. The deep brain stimulation group includes engineers, data scientists, nurse practitioners, physical therapists and some prominent names in neurosurgery.

Their story, and that of Rafael Hernandez, is about what can happen when medicine and technology come together. Their story is about the convergence of science and engineering in the human brain, but it’s ultimately about hope.

The Good Doctor

Doctors who specialize in children’s movement disorders are rare.

A provost associate professor of biomedical engineering, neurology and biokinesiology at USC Viterbi and the Keck School of Medicine, Sanger has treated hundreds of children suffering from the worst neurological disorders, mostly at CHLA.

“What makes Dr. Sanger unique in the medical world is that in addition to being a child neurologist, he’s also an electrical engineer and computational neuroscientist,” says Mark Liker, a clinical assistant professor of neurosurgery at the Keck School.

That background gives him tools to try to solve a tough puzzle that has plagued scientists: How the brain encodes the signals that fire through its network of neurons. It’s a critical question to experts trying to not only fight dystonia, but also reverse paralysis and cure diseases like Parkinson’s.

Sanger uses engineering to discover treatments and pursue devices, like exoskeletons and artificial spinal cords, that could help children with movement disorders. The Iron Man analogy isn’t too farfetched if you’re sitting in the Sanger Lab watching him remotely control a robotic arm using only his forearm muscles.

Among all the movement disorders he sees, the most frustrating is dystonia.

Some of the children in Sanger’s care have their arms tied down to their wheelchairs so they don’t hurt themselves involuntarily. Others crawl crablike on the floor.

“In many cases their cognitive functions are perfectly normal. They know what’s going on—they want to communicate, they want to move, but their bodies won’t let them,” Sanger says.

Since officially starting the DBS program at CHLA seven years ago, Sanger has seen once-wheelchair-bound children stand and walk again.

The key is a procedure that goes back more than a century, but is only now being used to safely treat children with movement disorders, thanks to Sanger and his team.

Deep Brain Stimulation and the Girl No One Believed

Wires in the brain bring relief to a Southern California teen with dystonia.

Deep Brain Stimulation

DBS entails drilling into a patient’s skull and zapping the deepest structure of the brain with electricity. Physician Roberts Bartholow may have been the first to try electrically stimulating the brain of a human patient—back in 1874. The patient was a 30-year-old woman with a cancerous ulcer that opened a hole in her skull. Bartholow found that he could turn off pain centers in her brain by electrically stimulating her cortex. The modern era of DBS began in the 1980s through the use of stimulation to treat tremor. It has since been used to treat more than 40,000 people with Parkinson’s and essential tremor worldwide, and is currently undergoing clinical trials as a treatment for depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

In 2016, Sanger’s team discovered a targeted way to use DBS to treat dystonia patients. Thanks to his experience with treating epilepsy, neurosurgeon Aaron Robison of CHLA and the Keck School developed a technique to insert temporary electrodes that stimulate the deep structures of the brain—all while recording the brain’s activity. The doctors use microscopic wires to monitor individual neurons. Combine the technique with Sanger’s testing regime and data analysis, and the research team now has helped many children and young adults like Rafael Hernandez, while amassing what’s believed to be the largest-ever dataset on the brain of children with dystonia. The voluminous data may help other researchers make important discoveries about the brain.

Despite missing nearly half his brain, Rafael Hernandez can throw a baseball because of two thin wires threaded through his skull. They send finely tuned electrical pulses into regions deep in his brain called the globus pallidus and the thalamus. The wires are connected to a pacemaker-like device implanted below his collarbone.

No one knows exactly why DBS works. Sanger believes that the electrical impulses from the wires cause nerve cells to fire as a group, overriding the abnormal signal patterns coming through those nerve cells. In effect, DBS may substitute its pattern of neural firing for the disabling pattern that creates dystonia.

A Dystonia Answer?

Sanger stresses that dystonia is a symptom of a problem in the brain. It’s not a disease itself.

For my son, it’s been 110 percent improvement. Since the DBS four years ago, Rafael has also been seizure-free.

MARIZA HERNANDEZ

What scientists know is that faulty brain signals cause muscles to spasm and pull the body into twisting, repetitive movements or abnormal postures. It can be caused by an inherited gene, or secondary to damage to the central nervous system (like what happened to Rafael Hernandez). or birth trauma. But in many cases dystonia appears mysteriously. It can affect a single muscle or extend to the entire body. As many as 250,000 people in the United States have dystonia, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, making it the third-most common movement disorder behind Parkinson’s.

Although DBS has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat Parkinson’s since 1997, and it has a humanitarian device exemption to treat inherited dystonia, patients seeking DBS for acquired dystonia do so off label.

Studies suggest that only about 50 percent of children with acquired dystonia see a significant benefit from DBS. But Sanger and his team have recognized a significant benefit in more than 70 percent of these children.

“For my son, it’s been 110 percent improvement,” Mariza Hernandez says. “Since the DBS four years ago, Rafael has also been seizure-free.”

On Aug. 21, Sanger and Rafael Hernandez had a reunion on USC’s Dedeaux Field. Four years had gone by since Rafael’s procedure, and Sanger, who hadn’t seen Rafael since, came out to watch him pitch. They even played catch together.

For Sanger, it was a rare occasion to witness the longterm effects of DBS.

“Did I surprise you?” Rafael asks.

“Yes, you’ve changed so much,” Sanger says. “You’re all grown up now.”

Rafael Hernandez points to Sanger’s heart. “I want you to always remember me right here. Right here! And whatever happens, I always got your back, Dr. Sanger. You’re my homeboy!”

Sanger turns to Mariza Hernandez. He says, almost to himself: “This is why I do this.”

This story is adapted from an article in the Autumn/Winter 2017 issue of USC Viterbi Magazine. Interested in hearing more about deep brain stimulation for dystonia? Listen to USC Viterbi’s podcast below.