The USC study examined graduation rates of black student-athletes from 65 universities. (Photo/iStock)

Black athletes’ graduation rates lag at U.S. universities with top sports teams

USC’s Shaun R. Harper finds that among 65 leading universities, black male athletes continue to graduate at lower rates than other student-athletes, black non-athletes and undergraduates in general

As NCAA Division I schools begin March Madness with an eye toward the national championship in men’s basketball, many of them, if not most, will have teams with a majority of black players.

When those colleges and universities go after the College Football Playoff title this fall, many of them also will have teams composed mostly of black players.

And yet, black male student-athletes won’t be so easy to find elsewhere on those campuses, and they will likewise be disproportionately underrepresented come graduation, according to a new report from the USC Race and Equity Center.

Shaun R. Harper, the center’s executive director and a Provost Professor at the USC Rossier School of Education and the USC Marshall School of Business, authored the study, updating and adding to research first published in 2012 and last revised in 2016.

This new research by Shaun Harper sheds a light on a critically important issue and one that universities must continue to address as they commit to more diverse and inclusive campuses.

Michael Quick

“This new research by Shaun Harper sheds a light on a critically important issue and one that universities must continue to address as they commit to more diverse and inclusive campuses,” Provost Michael Quick said.

“I’m proud of the work being done by Dr. Harper at the USC Race and Equity Center. It is timely, relevant and essential for understanding our highly valued athletic programs.”

Most dominant, competitive schools

Harper examined graduation rates and representation rate inequities within the so-called Power Five conferences: the Atlantic Coast, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and Southeastern conferences. Those conferences — spanning 65 universities in total — represent the most dominant and competitive schools in NCAA Division I sports, and thus, Harper said, the most likely to demonstrate problematic trends relating to African American male student-athletes.

Black men made up 2.4 percent of the undergraduate population at Power Five schools, but comprised 55 percent of their football teams and 56 percent of their men’s basketball teams.

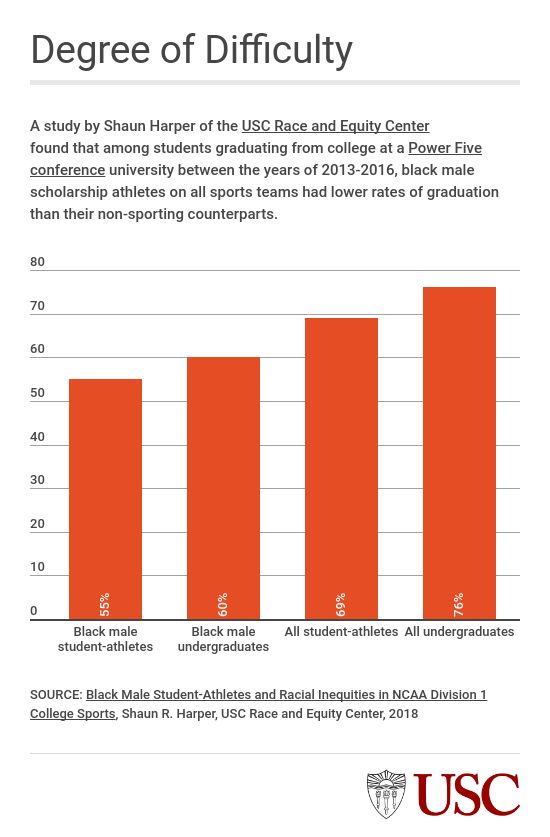

The report shows that just over 55 percent of black male student-athletes graduated within six years, compared with 60 percent of all black undergraduate men, 69.3 percent of all student-athletes and 76.3 percent of all undergraduate students.

“Over the past two years, 40 percent of these universities have actually had black male student-athlete graduation rates that have declined,” Harper said. “We’re supposed to be getting better, but actually 40 percent of these places have gotten worse.”

Harper used the NCAA Federal Graduation Rates Database to find six-year graduation rates of students who graduated from college between 2013 and 2016.

“The [NCAA] has claimed in television commercials that black male student-athletes at Division I institutions graduate at rates higher than black men in the general student body,” the report says. “This is true across the entire division, but not for the five conferences whose member institutions routinely win football and basketball championships, play in multimillion-dollar bowl games and the annual basketball championship tournament, and produce the largest share of Heisman Trophy winners.”

The federal database doesn’t account for undergraduates who transfer between schools — unlike the NCAA’s own measure, known as the graduation success rate. However, the graduation success rate doesn’t capture data for non-student-athletes, making comparisons using that data difficult. In addition, Harper’s report noted that no published evidence or reports suggest that African American male student-athletes transfer at different rates than other groups.

Taking action on black athletes’ graduation rates

Harper suggests solutions that bring together the NCAA, sports media, and athletes and their families. Those proposals include a call for the NCAA to disaggregate their student-athlete data by race, sex, sport, division and conference, to highlight discrepancies and prevent false claims about graduation rates that can arise from aggregated.

But Harper said that the schools themselves had the most to offer.

Among his recommendations for schools:

- produce demographically disaggregated data on their student-athletes

- work with athletic directors and coaches to establish strategic plans around racial equity and that improve the holistic development of student-athletes

- confront bias and stereotypes on campus

- recruit black students who are not athletes

“While leaders in the NCAA and Power Five conferences have important roles to play in reducing the exploitation of young black men, no one is more responsible for systematically decreasing racial disproportionality in graduation rates than universities and their athletics departments,” Harper said. “These inequities are not going to correct themselves — campuses must enact multiple strategies and high levels of accountability.”