Photo By Adam Voorhes, Styling By Robin Finlay

Revolutionizing Cardiac Surgery

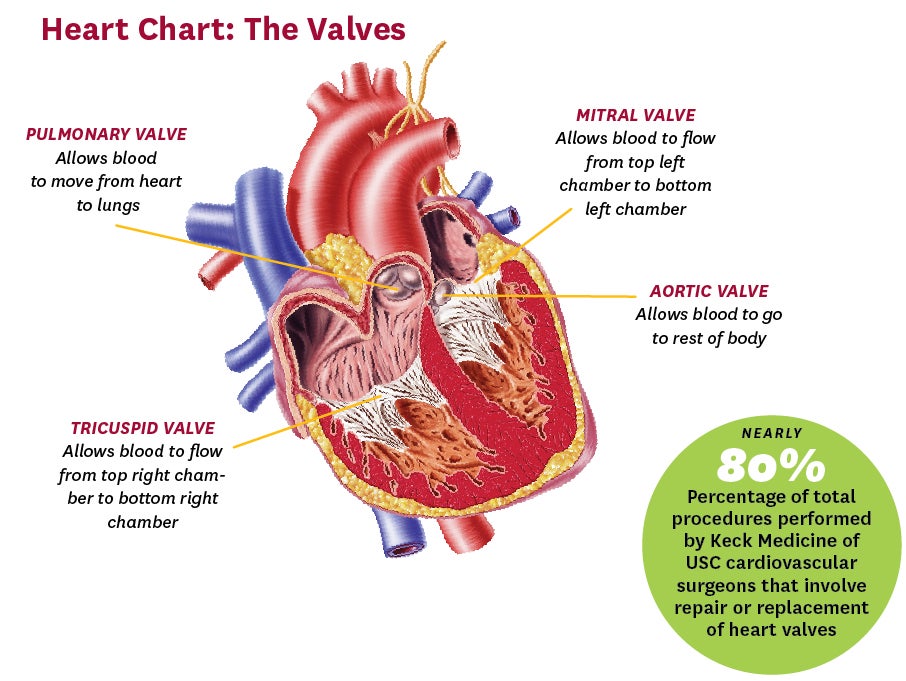

Keck Medicine of USC surgeons make once-extraordinary heart surgeries refreshingly routine.

As recently as a decade ago, fixing someone’s leaky heart valve was a major repair. Surgeons had to make as much as a 5-inch-long incision in the chest and cut through the breastbone to reach that most vital of vital organs, the heart. And even when the surgery was over, it wasn’t over. Recovery from open surgery took weeks, sometimes months, and during that time patients and doctors waited and hoped there would be no complications.

Times have changed.

There have been breathtaking changes in heart surgery in the past few years, says Vaughn Starnes, an internationally recognized cardiovascular surgeon with Keck Medicine of USC. Today, Starnes routinely performs lifesaving valve repairs through a few incisions not much more than an inch long. By performing repairs and implanting replacement valves with slender instruments inserted between the ribs, surgeons can greatly reduce blood loss, risk of infection and pain after surgery.

“The changes in heart surgery in recent years have been nothing short of revolutionary,” says Starnes, chair of the Department of Surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. Many of his patients now bounce back so quickly they often ask if they can return to work or travel before their first postoperative visit.

Surgeons at USC’s CardioVascular Thoracic Institute (CVTI) saw the potential of less invasive surgery in the early 2000s. They decided to become experts in minimally invasive valve repair, becoming some of the first in the nation to embrace and perfect the technique. At the time, minimally invasive heart surgery had promise, but not much in the way of a track record—so it was a bold move.

Today, minimally invasive surgery is the standard for most valve replacements. CVTI surgeons now perform more than 150 such surgeries a year—more than any group in Southern California.

Keck Medicine of USC heart surgeons have a history of adopting innovative techniques they believe will significantly help patients. They were among the pioneers of robotic heart surgery. They were among the first in the western United States to implant an artificial heart in a patient and, using new technology, discharged her safely to the comfort of home.

And as much as technology is driving the practice of medicine, Keck Medicine of USC surgeons understand that providing top care means never losing sight of the basics: solid diagnoses, comprehensive treatment plans and teams of health professionals dedicated to the needs of each patient.

Craig Baker, associate professor of surgery at Keck School of Medicine of USC and chief of cardiac surgery at LAC+USC Medical Center, says the tailored team approach applies to all cardiac patients seen at Keck Medicine of USC. “We treat every patient as unique and every patient as an individual,” Baker says.

Keck Medicine of USC’s Ramen Chmait, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Keck School of Medicine of USC and director of Los Angeles Fetal Therapy, grabbed headlines last year for performing what’s called an aortic valvuloplasty—the use of a balloon to open a narrowed heart valve—on a fetus for the first time in Southern California. Chmait consults with USC cardiac surgeons and pediatric cardiologists at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA), who are Keck School of Medicine faculty, to create a plan with the best chance of success.

“We work together to diagnose the conditions and come up with a plan so that at birth the baby is in the best condition that is possible,” Chmait says.

Advances in operating on both fetuses and babies means that more infants and children with heart problems are surviving, and it’s now typical for Keck Medicine of USC surgeons to continue to care for them as they age. There are now more adults living with congenital heart disease than children, says Baker, who also serves as surgical director of the Adult Congenital Heart Program at Keck Medicine of USC. “We have established a transition clinic at CHLA to facilitate the care of congenital heart disease patients as they mature into adulthood,” he notes.

At a time when technology has allowed for revolutionary changes in heart surgery, Keck Medicine of USC’s team says the revolution is just beginning.

CVTI’s heart surgeons recently started performing even less invasive operations called percutaneous procedures. Using catheters threaded up to the heart through a vein in the leg, the surgeons performed their first percutaneous valve replacement in 2011. Since that time, Keck Medicine of USC surgeons have performed more than 200 of these procedures, which may pose even less risk than today’s typical minimally invasive operations.

They have also used percutaneous techniques to repair aortic dissections—potentially fatal tears in the wall of the aorta—with high survival rates and fewer complications.

“It has been an exciting few years in cardiac surgery,” Baker says, “and we see many more exciting changes on the horizon.”