Once homeless, USC neuroscience grad uses grit and determination to pursue his dreams

Tenacity and a belief in the power of education helped transfer student Nicholas Chapman build a better life for himself. He wants to become a doctor to give others the same chance.

After yet another morning tinged with the smell of whiskey and coffee on his father’s breath, Nicholas Chapman left home to live on the streets. He had finally had enough of the screaming matches, enough of the strict rules.

Chapman grabbed his cell phone. A friend gave him a backpack, $20, a change of clothes and some deodorant. With that, he became one of the thousands in Southern California who have no place to call home.

He was only 17.

But he felt hopeful. He was leaving an unhealthy environment, and he had a vague plan for his future: getting an education.

Eight years later, he is graduating from USC and plans to become a doctor. His road to get here has been rocky, but he refuses to see himself as a survivor. Anybody could have done what he did, he said. He just wants to do everything in his power to protect others from similar hardships.

“I know how it is to almost fall through the cracks, the fear as if you will lose everything,” Chapman said. “I decided I didn’t want to ever have anyone else have that feeling of losing their life, so conserving lives is my idea.”

USC grad overcomes early obstacles on path to career in health care

The 25-year-old plans to pursue that vision with the skills he gained at USC. He graduates this month with a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience from the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Medical school is up next. He’ll work on his applications later this year after taking the MCAT exam. As a doctor, he can make a tangible difference in people’s lives, he said.

“There’s no doubt this is what I want to do, in terms of aiding people. I want to put a mask on and help a person, then take the mask off and also help a person. Advocacy will always be a part of what I do.”

It’s a lesson he learned at a young age from his mother. The two left the United States for her native Brazil when Chapman was 2. They lived in Curitiba, a city near the coast about 250 miles south of São Paolo. She struggled to find work and would tell her young son that education was his best path out of poverty.

Seeing no way forward in Brazil, she encouraged him to return to the U.S. to better his life. He moved in with his American father in Long Beach at age 14.

Chapman had to learn to read and write in English as a teenager. He hid his struggles from teachers and peers, taking strategic bathroom breaks to avoid reading out loud in class.

Then there was the strained relationship with his dad, a topic he discusses openly.

“My dad’s an alcoholic,” he said. “He knows that. My whole family knows. I think it’s important for people to understand that it’s just the reality of life. That’s sometimes just how things are.”

He also talks honestly about when he got caught sneaking out to visit friends a week before Thanksgiving in 2012. His dad had grounded him for a year and a half already over another issue, and no end to the punishment was in sight. Chapman decided it was time he left for good.

“You have to make choices in life and sometimes they are hard,” he said. “Sometimes you sacrifice a lot. I stayed in Metro stations. I stayed in homeless shelters. I stayed on friends’ couches.”

To survive, he played chess for hours at coffee shops, where older players befriended him and bought him food. Because he was young, kids liked to watch him play, and soon he talked their parents into hiring him for $20-an-hour lessons.

Although he had dropped out of high school, Chapman remembered his mother’s advice: get an education. He visited a $1 bookstore in downtown Long Beach, where he pored over economics textbooks for hours. He earned his GED, then enrolled in classes at Long Beach City College.

He did well at first, but lack of sleep and the constant grind of day-to-day survival caught up quickly. His grades slipped. “My 4.0 went to a 1.7, just like that,” he said.

Desire to help others set USC student on mission to study medicine

Then at age 19, stability came in the form of a part-time job at a mom-and-pop hobby store. He sharpened his sales skills and soon became a manager. He slept some nights in the shop, curled under a fire blanket. His grades recovered.

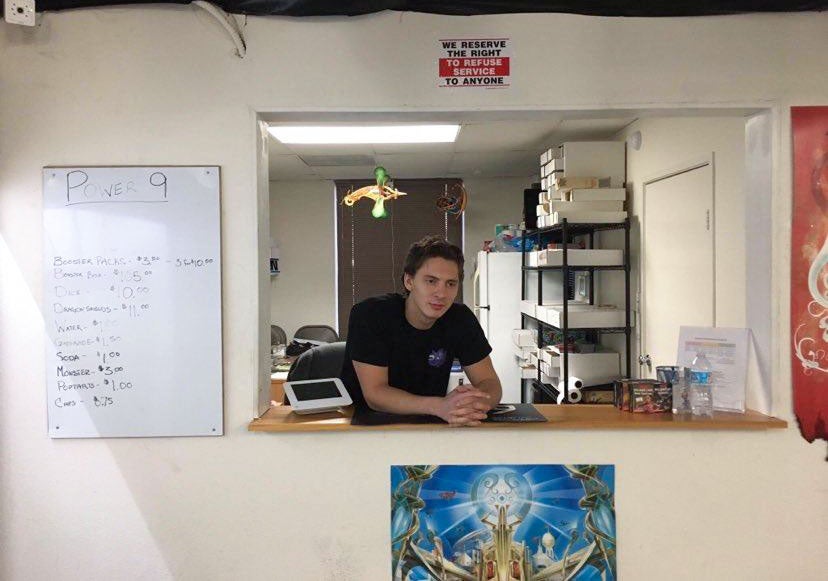

A year later, the store closed. But Chapman had saved some money and made friends with a few regular customers. They launched their own hobby shop, called Power 9, with Chapman as CEO. They sold figurines, board games and “other nerdy things,” he said. He soon could afford a car, then a rented room in an apartment.

Although he felt secure in his personal life, his business and economics classes left him uninspired. Nothing clicked. Then one day, the uncle of a boy he tutored had an epileptic seizure in front of his family and Chapman. Nobody knew how to react. Eventually, the man regained consciousness, but Chapman felt shocked and helpless.

“I went to that $1 bookstore, grabbed a human biology textbook and read all about the nervous system,” he said. “That’s when I started falling in love.”

He switched his major from economics to psychology. He planned to transfer to the University of California system or USC, with the goal of applying to medical school. But his academic counselor said with the string of poor grades early in his college career, he had no chance.

Chapman applied anyway, relying on advice from a USC admissions adviser. He got into three UC schools and USC, and he enrolled as a Trojan in spring 2018.

USC transfer student forges his own way forward

Life as a transfer student was rough at first. Chapman commuted 45 minutes each way from his Westwood apartment to the University Park Campus. He had little money for food. He knew he wanted to be a doctor, but how could he achieve that goal?

“I had a large course load, but it was unclear what courses I needed,” he said. “I didn’t know what financial aid would cover or what programs there were to support me.”

As he gradually found his bearings, Chapman realized research skills and internships would shine on his med school applications. So he blitzed professors at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles with emails.

Mark Krieger, senior vice president and surgeon-in-chief of CHLA’s Department of Surgery, recalls getting a request from Chapman to shadow a few surgeons. He was impressed by the young student’s determination.

“To become a neurosurgeon, you have to have basic tools like intelligence, diligence and the ability to work with other people, and he certainly has that,” said Krieger, a professor of clinical neurological surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “But the other thing you need is grit. You need to be able to overcome obstacles and work through barriers, and Nicholas has certainly shown that over time.”

Chapman’s persistence paid off with internships in neurosurgery and radiology. He analyzed brain scans, observed many surgeries and helped write a conference paper on how children with cancer recover from radiation treatment.

“He works at a much higher level than the standard undergraduate student,” said Natasha Lepore, associate professor of research radiology at the Keck School of Medicine. “He’s certainly at the same level as some of the PhD students I’ve known.”

Through medicine, neuroscience grad aims to give others a better life

Now as he moves into the next phase of his life, with medical school planned for fall 2021, Chapman took time to look back on his experiences. He summed it up succinctly.

“My life has been about survival and lost innocence,” he said. “Working at Children’s Hospital, you see that same innocence diminish when kids realize they are going to die. It’s the same innocence you see lost when a transfer student comes in and struggles. I lost that innocence at a young age, being on the streets.”

If Chapman achieves his goal of becoming a doctor, he feels he will have gained resources and credibility that he can use to help others. And perhaps sharing his past will give someone the courage or persistence they need to survive.

“There’s some kid out there on the streets crying in fear, or getting abused by their parents, or unable to have an education,” he said. “I want them to see my story and realize that they can push through, that they should conserve life and believe in themselves.”