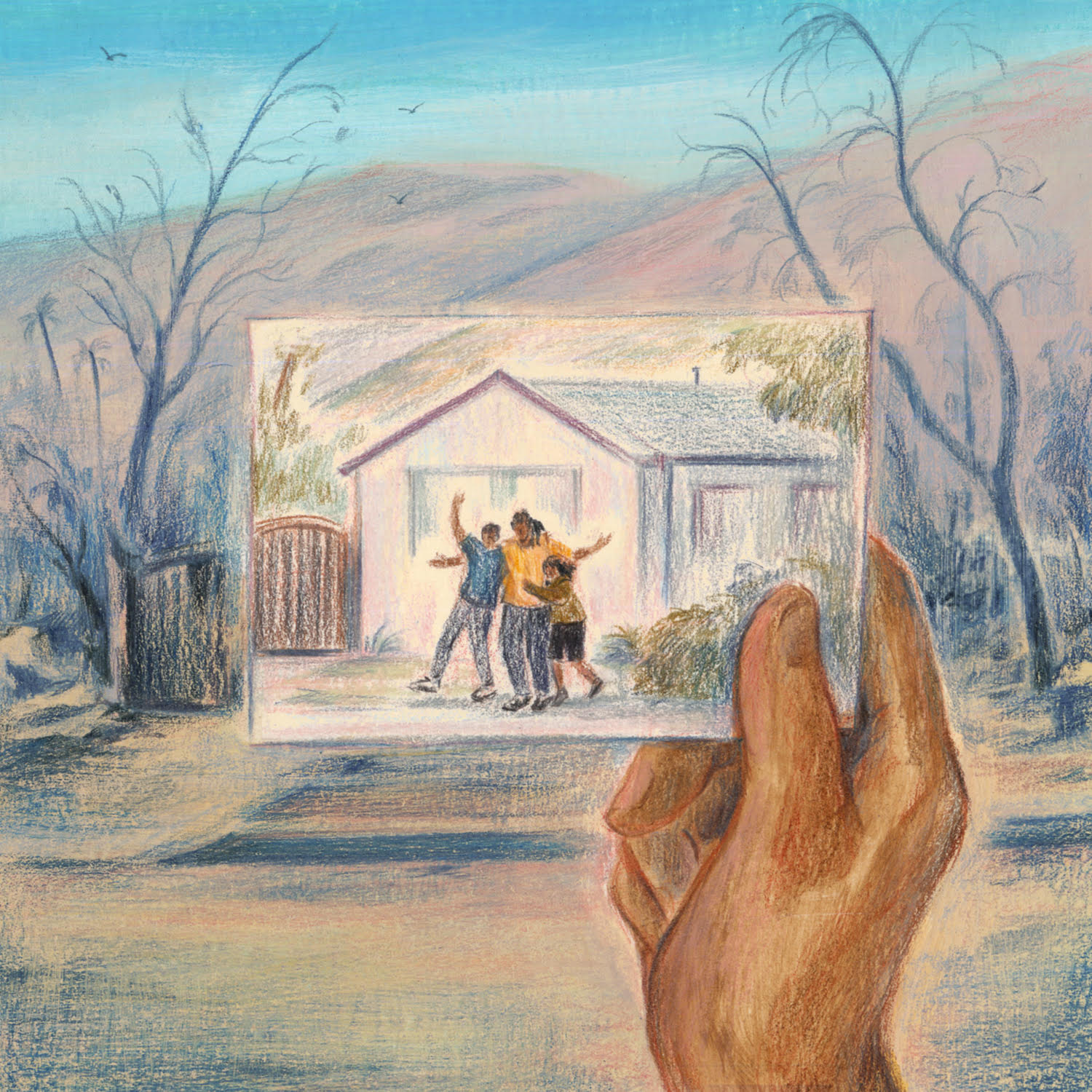

In the wildfires’ aftermath, the stakes have never been higher for USC researchers to apply innovative solutions that move the needle on sustainability, community engagement and the reimagining of Los Angeles. (Illustration/Sally Deng)

Rebuilding Los Angeles

USC experts share their expertise on how Angelenos can rebuild their communities stronger and better after January’s wildfires.

As historic architect Peyton Hall looked out his window and across the street from his Sierra Madre home on Jan. 7, he saw a massive orange glow in the sky: The Eaton fire was closing in. The scale of the disaster became clearer as the flames spread, and Hall joined his neighbors in fleeing the advancing disaster. After 26 years of teaching heritage conservation programs at the USC School of Architecture, the professional became personal as his mind leaped to what it would take to rebuild his community in the wake of a catastrophic wildfire.

“I’ve seen a lot of big things happen in my 45 years living in Los Angeles,” Hall says. “This is way beyond anything in terms of importance and urgency and difficulty. It’s unspeakable.”

The January 2025 Eaton and Palisades wildfires will likely go down as one of the most destructive and expensive natural disasters in our nation’s history. The triple threat of back-to-back wet winters that spurred vegetation growth, record-low fall precipitation and a significant Santa Ana wind event created extreme fire conditions. The largest fires eventually took 29 lives, burned more than 37,000 acres, destroyed more than 16,000 structures and placed more than 150,000 people under mandatory evacuation orders.

As Angelenos — especially those in the Altadena and Pacific Palisades communities — struggle to recover from the wildfires’ devastating toll, questions remain: What is the best way to rebuild? And can it be done in a way that is quick, sustainable and preserves the unique characteristics of what was lost?

I’ve seen a lot of big things happen in my 45 years living in Los Angeles. This is way beyond anything in terms of importance and urgency and difficulty. It’s unspeakable.”

Peyton Hall, USC School of Architecture

In the wildfires’ aftermath, the stakes have never been higher for USC researchers and practitioners from across disciplines to apply innovative solutions that move the needle on sustainability, community engagement and the reimagining of a city known for its ability to reinvent itself again and again.

USC faculty with expertise in critical fields such as air and water quality, health care, landscaping, soil stability and contamination, population density, building codes and individual behavior, among other research areas, can have a major impact on bettering the understanding of what led to this scale of destruction — and what changes need to be made to prevent it from happening again.

Building for the future

In 2018, architect Geoffrey von Oeyen, principal of von Oeyen Architects and Geoffrey von Oeyen Design, had just finished redesigning a house for his brother in their hometown of Malibu when the Woolsey wildfire broke out. The blaze devastated the Malibu area and destroyed the home as von Oeyen helped his brother and parents evacuate the city. Having monitored the week’s wind conditions through a weather app, he’d known that a wildfire was possible.

“I grew up evacuating from fires as a kid, so I already knew what it felt like,” says von Oeyen, an associate professor of practice at the USC School of Architecture since 2012. “But the Woolsey fire was so big and so powerful that it swept across all of the Santa Monica Mountains at virtually the same time.”

Permit restrictions on the original home — a 1960s-era ranch house — limited the design methods von Oeyen could execute in the renovation. The structure was left with features that made it prime fuel for a wildfire, such as wooden fencing, a wooden retaining wall and a ventilated attic that allowed embers to enter the home and ignite.

When he rebuilt the home last year, von Oeyen was free to introduce several measures to mitigate wildfire risk. He used insulated roofing instead of a ventilated attic; a concrete retaining wall to shield the home from its wildland border and the neighboring house; and a concrete, rock and gravel driveway. He also avoided using large plants near the home.

“We focused on sustainable aspects of the house that could help fireproof the structure, such as natural ventilation, so we don’t have a house that’s mechanically drawing in lots of air — and potentially embers — into the ductwork,” von Oeyen says.

Other upgrades included a generator sequestered in a concrete bunker and a sprinkler system that, once activated, will draw from city water and automatically switch to drawing from the home’s pool once the city’s water runs out of pressure. The sprinkler system is plumbed to the roof and designed to wet the landscape and the whole house.

The Franklin fire, which happened a few weeks before the Palisades fire, created a burn scar in central Malibu that blocked the Palisades fire from spreading west of Malibu, where the rebuilt home is located. While von Oeyen acknowledges that some of these upgrades might be outside the budget of many Californians, he argues that newly built and existing homes targeted in the rebuild and throughout the state must be retrofitted for wildfire safety regardless of their location.

“Why are we not incentivizing folks to build resiliently, to make sure that we don’t have a problem in the future when fires inevitably come through neighborhoods that are nowhere near wildlands?” asks von Oeyen, whose younger son’s school in the Pacific Palisades partially burned down in January. “It would translate to fewer houses burned down. That means we’d have fewer insurance claims, fewer FEMA expenditures and fewer emergency relief funds from the state. We’d be investing in the future.”

He also argues that sustainability must be central to any conversation regarding the rebuild. “If we keep using carbon-intensive building processes, we will exacerbate the atmospheric conditions that lead to more frequent and stronger climate events, such as wildfires,” he says.

Why are we not incentivizing folks to build resiliently, to make sure that we don’t have a problem in the future when fires inevitably come through neighborhoods that are nowhere near wildlands?

Geoffrey von Oeyen, associate professor of practice at the USC School of Architecture

Rebuilding to last

Professor Bora Gencturk of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering says that one of the most significant factors that accelerated wildfire spread in both Altadena and the Pacific Palisades is the fact that in the United States, more than 90% of residential constructions — especially single-family homes — use wood for framing and other components due to the wide availability of lumber. Compared to other regions of the world, such as the Middle East or parts of Africa — which rely on less flammable materials such as reinforced concrete — most U.S. homes are ill-suited for the wildfire risks that California poses.

“It is really necessary for us to consider different materials, even if they are existing conventional materials, that are resistant to wildfires,” says Gencturk, who also serves as director of the Structures and Materials Research Laboratory out of USC Viterbi’s department of civil and environmental engineering. He argues that materials such as concrete and concrete variants are not flammable, don’t generate smoke when exposed to flames and don’t produce embers that can carry fire from roof to roof far from the source of the wildfire — so that when they catch fire, they are much easier to control.

Roofs, Gencturk says, are the first line of defense a home has against a wildfire.

“With wildfires, the wind is a big component because it carries all the embers, which mostly land on the roof because it’s the largest surface area,” Gencturk says. “We know that fire usually gets into homes through the roof. But if we can build our roofing with materials that are fire-resistant and lightweight, that’s going to help limit the amount of destruction.”

Many California roofs are built with shingles made from materials such as paper and petroleum products, which burn quickly once in contact with embers. Gencturk says that California homes should transition to using roof materials like clay, metal or other new technologies, such as composite cladding — a combination of reclaimed wood fiber and recycled plastic that acts as an additional skin to protect the exterior of buildings from extreme weather conditions. Fire-rated windows can also add a layer of protection because of their ability to withstand high temperatures and prevent the spread of smoke and flames.

Gencturk says reducing excess vegetation and potential fuel near structures and creating concrete barriers or distance between buildings can greatly reduce the risk of fire spread.

Architect Liz Falletta, a USC Price School of Public Policy professor, agrees. She says creating a greater distance between residential housing and wildlands is a method that should be considered in the rebuild. She says denser housing — especially in Altadena — is key.

“You could create housing denser and taller but with the same number of units further down the hill and then preserve the rest of the land as communal open space with fire-resistant landscaping,” the South Pasadena resident says. “That way, we won’t have to build in areas on the interface between urban neighborhoods and the wildlands.”

Falletta argues that kind of multifamily housing can build a better sense of community and allow for more sustainable land use. Plus, from an equity and affordability standpoint, “We’re going have to build densely one way or the other,” she says. “If we want to be an equitable city, single-family homes are going to be so far out of reach for most Angelenos.”

If we can build our roofing with materials that are fire-resistant and lightweight, that’s going to help limit the amount of destruction.

Professor Bora Gencturk, USC Viterbi School of Engineering

Preserving the essence of a community

As a historic architect, Hall identifies the significant characteristics of buildings, neighborhoods and cities. He uses the concept of a “palimpsest” to describe the layers of information that make up the character of a neighborhood — including the architectural style of the buildings, the landscape, the streets and sidewalks, the density of housing, retail and community centers. He emphasizes that in the wake of these disasters, it’s “everybody’s job” to think about those layers together.

In the rush to rebuild, much can be lost without intentional planning.

“We call ourselves architects because we’re dealing with tangible landmarks and buildings, but we’re also talking about people and community,” Hall says. “It’s about keeping cities in such a way that the people want to be there, so that their anchors in community and family are recognized. The literal part of a building or reconstructing a building is really a mechanism for the less tangible things that define a neighborhood and a community.”

Hall recalls speaking with a co-worker whose house survived the wildfire in the Palisades. Though she didn’t lose her home, most of her neighbors lost theirs, along with the stores, churches and schools they and their families used to frequent.

Hall argues that a home without a community is hardly a home at all. “It’s part of their well-being,” Hall says. “It’s more than, ‘We lost our church, we lost our house.’ It’s more like, ‘We lost everything that anchors us to everybody we know, and everything we know and grew up with.’”

Hall wants to remind those involved with the Altadena and Pacific Palisades rebuilds that action with urgency does not have to come at the expense of preserving the history and character of the communities. “A house built in 1908 cannot be constructed the same way a century later,” Hall says. “And we actually don’t want to. This is an enforced opportunity to build something that’s more energy-efficient but could still have good character and be compatible.”

Having a seat at the table

Urban planner and researcher Santina Contreras started working in housing reconstruction and disaster relief in earthquake-prone countries such as Haiti and Indonesia. In her experience, regardless of the disaster, community engagement is often the first element of the recovery process that is sacrificed in favor of urgency — a mistake she believes can have hidden costs down the line.

“You can have a situation where all the houses get rebuilt, but if it doesn’t look or feel like it did before, if the people living there previously aren’t able to come back — was that a success?” Contreras says.

An assistant professor of urban planning and spatial analysis at USC Price, Contreras researches the power dynamics involved in engaging community members during and after hazards and disasters, and how the practice can promote greater equity during the recovery phase.

You can have a situation where all the houses get rebuilt, but if it doesn’t look or feel like it did before, if the people living there previously aren’t able to come back — was that a success?

Santina Contreras, USC Price School of Public Policy

Contreras says that a lot of recovery efforts she’s worked in lacked frequent and practical opportunities for “two-way communication” with community members to engage in and inform the process, leading to recovery outcomes that don’t match the needs and the interests of those communities.

To combat this, she recommends giving affected communities a seat at the decision-making table through regular opportunities for engagement such as community meetings and focus groups to collect input, and workshops to fill gaps in information, inform residents of resources and provide updates on what’s happening in the process and what to anticipate going forward.

Contreras says listening to that feedback, using it to modify and inform recovery activities, and returning again and again to check on identified goals is the important next step.

“Being open to that process will be important because what fits for Altadena will be different from what works for the Pacific Palisades,” she says. She also warned of the importance of being clear about expectations versus reality. “Unfortunately, it’s hard to imagine a rebuilt L.A. looking exactly like it did before — but there’s also opportunities for building back better and conversations about what that could look like.”

Contreras says she’s been in conversations with other researchers and practitioners to identify ways to combat gentrification and rent gouging by providing residents with resources that let them know what their options are moving forward and how to make the most well-informed decisions for the long rebuild process ahead.

“As a collective, we have many shared interests,” Contreras says. “But every community is different and has its own concerns. That’s why it’s critical to prioritize having in-depth conversations with folks about the needs and interests of their community. This will put us in the best position to have the most equitable recovery outcomes in the long term.”

Planning ahead

All the researchers agree that it would be cheaper to invest now in resilient design and construction, rather than pay the costs of cleanup, recovery and rebuilding in the future.

“Federal and state resources should be allocated through grants and tax incentives to rebuild these communities resiliently as an investment in the future,” von Oeyen says. “The federal and state governments, as well as private insurers, can save billions of dollars in the future if communities can withstand the inevitable wildfires ahead, which are anticipated to be more frequent and more severe over time.”

Gencturk believes the future is bright for weather-resilient home construction. He is currently working on a building method that uses a construction robot to print out layers of concrete using a 3D printer. He chairs a committee under the International Code Council that focuses on developing a code of standards for 3D-printed construction. He hopes the method will be available for Californians as early as 2030.

As the rebuild plays out in the months and years to come and the threat of wildfires remains high in California and increasingly beyond, politicians, key stakeholders and residents near and far from wildlands should envision a future of sustainable land use, resilient construction and strengthened communities.

The alternative, a rebuild that ignores the lessons of past disasters, could lead to destruction and loss more widespread than previously seen.

“I look out my window now, and I see burned hills,” Hall says. “When I hear helicopters, I look around for fire. There’s a new caution now, a new awareness about where we live.”

How are Trojans contributing to L.A. wildfire relief efforts?

USC faculty in critical fields such as air and water quality, health care, landscaping, soil stability and contamination, and population density, among other research areas, are using their expertise to contribute to a wide array of L.A. wildfire relief efforts.

- Through the Los Angeles Fire Human Exposure and Long-Term Health Study (L.A. Fire HEALTH Study), Keck School of Medicine of USC faculty are partnering with researchers from UCLA; the University of California, Davis; University of Texas at Austin; Harvard University; Stanford University; Yale University; and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center to assess the health impacts of wildfire emissions and evaluate “which pollutants are present, at what levels, and where, as the concentrations diminish over time.”

- Public Exchange, based out of the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, has launched a “community-driven effort” to help residents from areas affected by the L.A. wildfires test their soil lead levels at no cost. Its Contaminant Level Evaluation & Analysis for Neighborhoods (CLEAN) project will eventually create an interactive map showing sample locations and lead levels across the affected areas.

- Through Project Firestorm, Keck School of Medicine of USC Professor Frank Gilliland and colleagues are embarking on a “rapid-response epidemiological study” to investigate the health impact of wildland-urban fires. The study will draw from a cohort of 9,000 participants from USC from a previous COVID-19 study.

- USC Visions and Voices hosted “After the Flames: The Role of the Artist in Climate Justice and Sustainable Change,” a collaboration between the USC Thornton School of Music and USC Arts Now. The half-day symposium and teach-in on April 21 focused on the impact of the wildfires and exploring the intersection of creativity, climate justice and sustainability.

- The USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research conducted the LABarometer Wildfire Survey. Its findings provide “the first countywide snapshot of how Angelenos were affected by the wildfires based on their housing stability and income before the fires.”

- The USC Rossier School of Education, in partnership with the USC College Advising Corps and the USC Leslie and William McMorrow Neighborhood Academic Initiative, hosted a seminar on the college admissions process for high school seniors affected by the L.A. wildfires.

- Monalisa Chatterjee, an associate professor of environmental studies at USC Dornsife, is working with graduate student researchers from the school’s environmental studies and environmental data science programs to scrutinize California’s fire insurance landscape and navigate “the complexities of creating a new model by analyzing large datasets and talking to communities in high-risk areas.”

- The Trojan Family Relief Fund helps USC students, faculty and staff who have been displaced by the fires and need support with transitional expenses, such as temporary housing, family care and emergency supplies.