The remnants of the Majdanek concentration camp stand as a reminder of the atrocities of the Holocaust. (Photo/Danita Delimont, Getty Images)

USC Shoah Foundation-backed film Last Goodbye offers haunting reminder of Holocaust history

A visit by survivor Pinchas Gutter to his homeland is a recollection of the family he lost and the life he might have lived

As an 11-year-old boy in Poland, Pinchas Gutter’s world was blown apart.

His early years were idyllic. He was born in the bustling city of Lodz in 1932 to a deeply observant Jewish family of winemakers. As a child, Gutter remembers joyfully playing in the park with his twin sister, Sabina. In their family’s apartment, his grandfather would set aside coins for him to give to the hungry who might knock on their door, observing the Jewish tradition of tzedakah, charity for those who are less fortunate.

Then, in 1939, the German army occupied his hometown during an invasion that marked the beginning of World War II. So Gutter’s father sent him, his mother and his sister to safety in Warsaw, where he would soon join them. But instead of finding relief from the Nazi threat, they were made to live in the city’s Jewish ghetto. In 1943, after surviving years of hardship that included the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Gutter and his family were rounded up and taken to the Majdanek concentration camp.

Remembering the Holocaust: An intense experience recalled

Gutter recounts the experience of being crammed into a boxcar with his family and hundreds of other Jews for the hours-long train trip from Warsaw to Majdanek, remembering the Holocaust in the virtual reality film The Last Goodbye. The documentary was co-produced by USC Shoah Foundation — The Institute for Visual History and Education at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

The film chronicles Gutter’s final visit to the camp, which is now a museum with well-preserved remnants from its darkest days. By wearing a special audio-visual headset, the audience experiences the trip — and most important, Gutter’s testimony as he tours Majdanek’s barracks, showers, crematorium and more — in room-scale, 360-degree virtual reality.

“My father found a space for us [where] we were reasonably safe, and he kind of surrounded us with his hands,” Gutter, now 86 years old, explains in the film as viewers are invited to inspect a train car that was used to bring Jews to the concentration camp. “I always imagined that [his arms were the] wings of an angel because he kept us together. My mother, my twin sister and I, we were like one, and I don’t remember how long we rode.”

Their small circle of safety was severed once they arrived at the camp, recalls Gutter as he stands near a barbed-wire fence on the campground. Men, women and children were separated. Gutter remembers spotting his sister in the distance as she made a beeline for their mother.

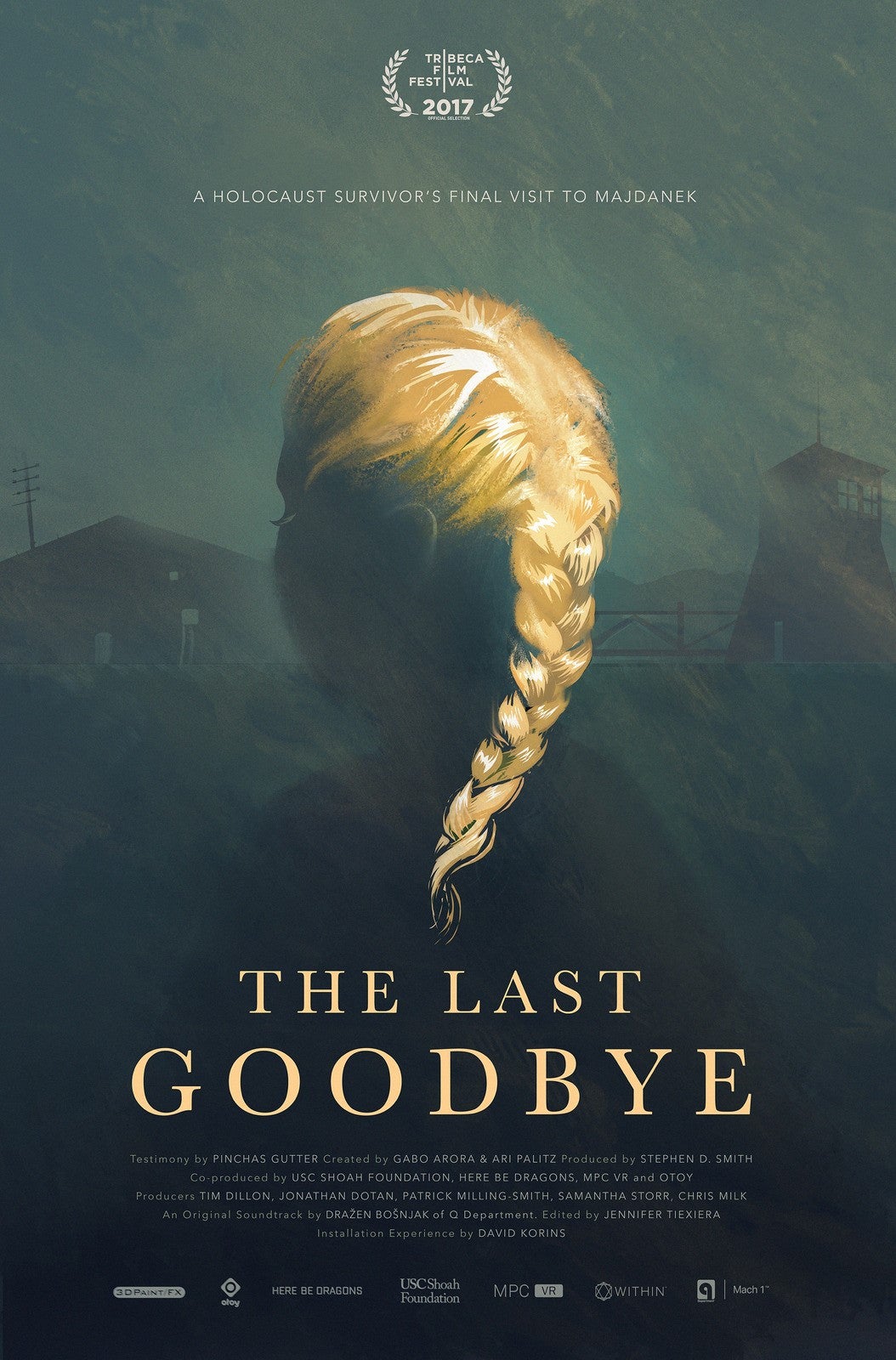

“As she was running, I was watching the beautiful gold braid that she had,” Gutter said. “She made it to my mother and she hugged her.”

That was the last time he saw his family. They perished in the gas chambers of Majdanek.

Gutter shares his story because he believes it is important for others to hear about these painful episodes in human history firsthand from the people who experienced them.

“It cannot be left to academics and historians to try and cut it up and then give their subjective view of what actually happened,” he said. Individual stories illustrate the nuance of events as they unfolded for each person and for each family, in keeping with USC Shoah Foundation’s mission.

USC Shoah Foundation preserves interviews remembering the Holocaust

USC Shoah Foundation is committed to preserving interviews with survivors and other witnesses of the Holocaust and other genocides so they can be used for education and action. The institute’s Visual History Archive holds about 55,000 testimonies, which in their full-length forms remain unedited to ensure the integrity of the accounts. This was partly a safeguard against Holocaust deniers, who often pounce on the slightest opportunity to sow unreasonable doubts, explained Stephen Smith, the institute’s Andrew J. and Erna Finci Viterbi Executive Director Chair of USC Shoah Foundation.

“We filmed The Last Goodbye in this same spirit of fidelity,” Smith said. “We made sure, for instance, that Pinchas narrated his experience while physically on site at Majdanek, rather than just in front of a green screen, and we agonized over how to accurately capture the sinister essence of the camp, mindful that it has since been turned into a museum.”

The technical elements of the filming were incredibly detailed. Scenes were shot in one of two ways, using either a 360-degree camera allowing viewers the ability to stand and look around a space, or photogrammetry, a technique in which tens of thousands of individual high-resolution photos capture a space and are then digitally stitched together so that the viewer can actually walk around and explore it in virtual reality.

The results are striking and deeply emotional. To hear Gutter describe his plight as the viewer walks by his side in the stark location where it took place is heart-wrenching. When he stands next to the barbed-wire fence, a brilliant green field stretching into the distance, we can imagine that last moment of seeing his mother and his sister in what must have been an endless sea of unfamiliar faces.

He tries to conjure his sister’s face, but it is something that has long ago escaped his memory.

“I cannot remember anything about her except for that golden braid,” he said.

Accolades for The Last Goodbye

The Last Goodbye premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2017 and screened at the Venice Film Festival and the Future of StoryTelling Festival. In February, the Advanced Imaging Society honored it with a Lumiere Award Special Jury Prize. The institute is currently considering where the film might be made available to viewers as part of a permanent installation.

The film expands on USC Shoah Foundation’s Dimensions in Testimony initiative, a collection of interactive biographies that allow people to have conversations with pre-recorded video images of Holocaust survivors and other witnesses to genocide. Gutter was the first survivor to provide his likeness and life story for Dimensions in Testimony.

Gutter, who lives in Toronto, has led university students on tours of Majdanek as a Holocaust educator for many years. But the trip in 2016 to share his story for the film is the last time he will return, he said, though the power of the place in his memories can never be erased.

“To say farewell to Majdanek would be impossible,” he tells viewers in The Last Goodbye. “Majdanek is part of me. My family is here. My father, my mother, my sister, Sabina, they are here. And I will always be here. Majdanek lives in me.”