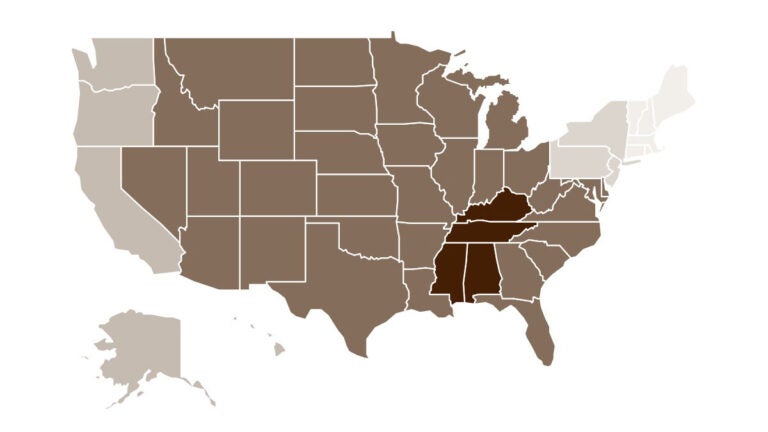

Infant mortality rates vary widely across the U.S. (USC graphic)

Study reveals where infant deaths are highest in the U.S.

To reduce the mortality rate, focus should be put on infants older than a month, analysis finds

If policymakers want to reduce the number of American infant deaths, their strategies should focus on those older than one month from lower-income families, a new study finds. The analysis compared American infant deaths to those of several European nations, as well as comparing figures between U.S. states.

Infants in the United States die at higher rates than those of comparatively wealthy nations. In 2013, the American infant mortality rate (IMR) ranked No. 51 internationally — on par with Croatia, despite having three times the GDP per capita. The new study could help narrow the search for answers to this disparity.

The study was published in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy in May; it was authored by Alice Chen of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics; Emily Oster of Brown University; and Heidi Williams of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The researchers investigated the IMR of the United States, Austria and Finland. Austria’s rate is roughly average for Europe, while Finland’s is one of the lowest in the world.

Census data

The three nations were compared using a complete census of births from 2000-05, linking them to infant deaths occurring within one year of birth. Data was sourced from the National Center for Health Statistics in the U.S., Statistics Austria, the Finland Birth Registry and Statistics Finland. Aggregate data was also used from the U.K. Office of National Statistics and Belgium’s Centre for Operational Research in Public Health Data.

In the post-neonatal period, which begins one month after birth, the U.S. has about 2.5 infant deaths for every 1,000 live births. That compares with just over two in Austria and 1.7 in Finland. U.S. deaths sharply escalate from there, ending at 4.65 at the one-year mark, compared with just 2.94 in Austria and 2.64 in Finland.

That steep slope implies that something unique to the U.S. is happening once babies return home from the hospital, Chen said. The discovery challenges the theory that low birthweights, which are linked to poor infant health, are the only driving force behind this disparity.

“It shows that focusing solely on improving health at birth, which has received a lot of attention, will be an incomplete solution,” Chen said.

Reporting differences

The causes of the American IMR have been the subject of much debate in the past. The researchers tested several theories: The simplest chalks the disparity up to reporting differences. The U.S. counts extremely preterm babies as live births, while other nations often record them as miscarriages or stillbirths. Another is that the U.S. simply has far more preterm births than in Europe.

To eliminate reporting differences, the researchers narrowed their sample size to babies born alone in the womb (as opposed to twins) at greater than 22 weeks of gestation and which were heavier than 500 grams. Doing so reduces the U.S. disparity by 40 percent.

Within that sample, birth weight accounted for 75 percent of the U.S. disparity relative to Finland or Belgium, but only 30 percent relative to Austria or the U.K. That suggests low birth weight is only part of the story.

Other considerations

The study also compared data within the U.S., finding a higher number of deaths in regions with greater poverty. Census areas like the Northeast and Pacific compare with Austria when it comes to infant deaths. The East South Central states (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee), on the other hand, have more than double the number of infant deaths at one year than the Northeast, which has the lowest.

Again, the data found that the rise in infant deaths across every region seems to accelerate at the one-month point.

Income inequality is also only a partial answer. Chen said that if the U.S. had Finland’s income distribution or if the East South Central U.S. matched the income distribution of the Northeast, it would explain only 30 percent of the difference.

Our results show that income explains very little of this gap.

Alice Chen

“Our results show that income explains very little of this gap,” Chen said. “Policies that focus on providing information and support to low socioeconomic mothers and infants after they are out of the hospital system can be particularly effective in reducing infant mortality. One such policy lever is home nurse visits that combine well-baby checkups with caregiver advice.”

Home nurse visits are found throughout much of Europe, including in Austria and Finland. The study noted that small-scale programs exist in the United States as well and have expanded under certain provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

Randomized evaluations of these programs have shown some early promise in reducing infant mortality and deserve further research, the study reported.

The study was funded by the Neubauer Family, National Institute on Aging Grant Number T32-AG000186 to the NBER (Williams) and National Science Foundation Grant Number 1151497 (Williams).