USC, Cancer and One Daring Mission

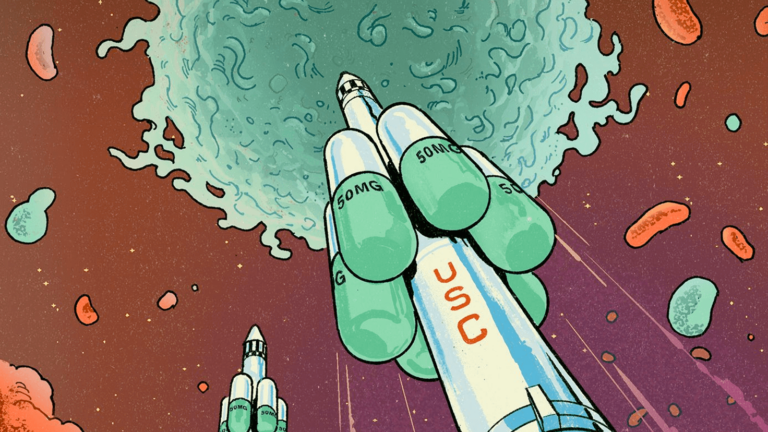

Powered by an energized cancer-fighting ecosystem at USC, Trojan researchers aim to help the nation achieve its Cancer Moonshot

Victor Perez didn’t think much about his weight loss. He had noticed some other changes, too. In the interest of being proactive, Perez, 38, of Long Beach, went to his primary care doctor.

His physician recommended a colonoscopy. “To be safe,” he told Perez.

On November 15, 2021, the day before his daughter’s sixth birthday, Perez learned he had colon cancer. A subsequent CT scan showed the cancer had spread to his liver. Stage 4.

“It felt like a death sentence,” says Perez’s wife, Joanne, who survived her own battle with Hodgkin lymphoma as a teen.

Perez enrolled in a clinical trial with a novel drug combination at USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center and began experimental chemotherapy treatments under the care of Heinz-Josef Lenz, J. Terrence Lanni Chair in Gastrointestinal Cancer Research and professor of medicine and preventive medicine. His first visit lasted 14 hours, taxing his body and his soul.

But, Perez says, “I knew it was giving me a chance to live.”

Every other week since, Perez has endured two consecutive days of chemo. He sees others: young and old, men and women, cutting across ethnic and socioeconomic lines, in worse shape than he is, clinging to life — and hope. Each trip awakens his humanity and intensifies his prayers for remedies.

I don’t want to see people suffering. I want there to be treatments that help people live.

Victor Perez

“I don’t want to see people suffering,” Perez says. “I want there to be treatments that help people live.”

It is a hope that millions of cancer patients around the globe share. It’s also a hope that USC is well-positioned to fulfill as a research institution and health care provider.

Earlier this year, two leading cancer researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC stood by President Joe Biden as he announced an ambitious national effort to slice the cancer death rate in half within 25 years. USC’s connection to what the White House has called the Cancer Moonshot is just one of the ways the university and the Keck School of Medicine are leading the charge to improve cancer treatment by addressing medical inequities in research; developing new approaches for deadly and rare cancers; supporting patients, survivors and caregivers; and learning more from people living with cancer.

A “Cancer Moonshot”

Cancer has long been a target of some of the world’s sharpest scientific minds, including researchers at USC, as well as health care organizations, nonprofit entities and public agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute.

At his final State of the Union address in January 2016, then-U.S. President Barack Obama unveiled a Cancer Moonshot program explicitly crafted to accelerate the rate of progress against cancer — a decade of progress in five years, the president beamed. To lead the ambitious program, Obama turned to Vice President Joe Biden, who had recently lost his 46-year-old son, Beau, to brain cancer.

Later that year, Congress overcame its partisan divide and passed the 21st Century Cures Act. The legislation devoted $1.8 billion to provide seven years of new funding for cancer research. It also created the Oncology Center of Excellence at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to streamline the review of promising treatments.

The earliest years of the Cancer Moonshot initiative marshaled the vast resources of the federal government, a critical component in such an immense scientific battle, and delivered enticing progress. There were important developments in treatments and diagnosis, including encouraging clinical trials and successful public health education campaigns that propelled screenings and early detection. There were also heightened efforts to reduce cancer disparities and critical advancements in sharing data, such as the Cancer Research Data Commons.

Meanwhile, new researchers poured into the field, driving breakthroughs in genomics, genome editing and diagnostics.

Cancer, one of humanity’s foremost universal enemies, was under siege in new and profound ways.

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, thwarted the momentum, interrupting cancer research and patient care for two years. Many patients skipped routine cancer screenings such as colonoscopies and mammograms. Research programs slowed amid mandated shutdowns. Outreach efforts such as health fairs, workshops and recruitment for clinical trials languished.

On Feb. 2, 2022, now-President Biden stood in the White House and announced a reignited commitment to the Cancer Moonshot, and he did so with a new, ambitious goal: to reduce the death rate from cancer by at least 50% in the next 25 years.

With a “fierce sense of urgency,” Biden pledged a vigorous fight against cancer and better support for cancer patients and their families.

“We can do this. For all those we lost, for all those we miss. We can end cancer as we know it,” he said.

The American Cancer Society reports that about 1.9 million Americans receive a cancer diagnosis annually, and about 600,000 die of the disease each year.

The American Cancer Society reports that about 1.9 million Americans receive a cancer diagnosis annually, and about 600,000 die of the disease each year. Biden’s headline-grabbing announcement — a monumental, galvanizing gesture from the White House — restored a national bull’s-eye on cancer.

Capitalizing on progress in research and patient-driven care as well as the scientific advances and public health lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic, the White House stressed a renewed, reinvigorated focus on cancer prevention, detection, diagnosis and treatment for all U.S. residents.

It was a call to arms transcending politics and an invitation to a daring scientific crusade.

In the White House that day, alongside cancer patients and government leaders, scientific disruptors and health care industry representatives, USC cancer researchers John Carpten and Peter Kuhn listened to Biden’s every word, inspired and hopeful that the president’s message would rally the nation in a way the space race had six decades ago.

“This is a conversation that touches everyone,” says Kuhn, the Dean’s Professor of Biological Sciences at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “It sets a mission for the nation and identifies cancer as something we need to do something about.”

A Specialized Battle

Carpten and Kuhn’s presence at Cancer Moonshot’s White House relaunch was a testament to their track records as combatants against cancer.

Carpten, who is the chair of the Biden administration’s National Cancer Advisory Board, directs the Institute of Translational Genomics at the Keck School of Medicine and is also the associate director of basic science for the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, one of the nation’s most innovative forces in cancer treatment, research, prevention and education.

An internationally recognized leader in cancer genomics, precision oncology and cancer disparities, Carpten studies DNA and RNA sequences of tumors using next-generation instrumentation. A prolific researcher, he has been the principal investigator or project lead on nearly two dozen National Cancer Institute grants over the last 15 years.

Carpten, Lenz, and Mariana Stern, the Ira Goodman Chair in Cancer Research and associate director for population sciences at USC Norris, oversee the ambitious project along with David Craig, professor and vice chair of the Department of Translational Genomics within the Keck School of Medicine. Together with other USC scientists and patient participants, they will be studying colorectal cancer in Hispanic patients such as Victor Perez. The study is supported by a five-year, $18.5 million grant from the National Cancer Institute, part of the Cancer Moonshot initiative.

Understanding how certain diseases and treatments affect underrepresented racial and ethnic groups is crucial to saving lives, Carpten says. “We have not done enough to understand how to engage with patients and communities to reveal the barriers and concerns and to create approaches that are sensitive and culturally appropriate.”

With about 500 Hispanic males, among the largest-ever cohorts of Hispanics in a clinical trial, Lenz — who leads the study — says they are addressing the knowledge gap on the molecular composition of colon cancer in Hispanics, who have the highest increase in early-onset colon cancer. Conducted with scientists from various disciplines at the center, researchers hope to drive a more comprehensive characterization of colon cancer in this population and spur improved diagnostic methods and therapeutic options.

“We’re taking advantage of our county’s patient population and learning from them,” Lenz adds. “It’s showing how cancer research isn’t done in an ivory tower at Norris, but we can learn from our patients.”

Bioscience Artillery

Meanwhile, Kuhn, a cancer physicist who runs the Convergent Science Institute in Cancer at the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, has directed cancer-battling research programs marrying physics and mathematics. With a particular focus on improving cancer diagnostics, treatments and access, the programs include spearheading the creation of the world’s first liquid biopsy database on cancer. Liquid biopsies represent a noninvasive way to help predict how a cancer will behave in the body, enabling doctors to spot cancers earlier and better determine treatment options. The liquid biopsies also promote increased access to care because it’s easier for most American residents to get blood drawn.

We need a tool to support decision making and that isn’t necessarily cutting someone open and looking for it. With these liquid biopsies, we’re finding and characterizing cancer with a blood draw.

Peter Kuhn

“We need a tool to support decision making and that isn’t necessarily cutting someone open and looking for it,” Kuhn says. “With these liquid biopsies, we’re finding and characterizing cancer with a blood draw.”

Kuhn’s ATOM-HP project, developed in collaboration with Jorge Nieva, associate professor of clinical medicine at the Keck School of Medicine, is providing doctors with real-time patient data from wearable technologies. Even if the patient is remote, physicians can access a comprehensive, data-driven and timely view of the individual’s health to inform treatment plans.

Beyond the Moonshot

USC’s fight against cancer extends far beyond Carpten and Kuhn, involving researchers across the university leveraging community partnerships, institutional infrastructure and USC’s built-in equity with patients. Investigators are pursuing bold, innovative work, analyzing novel ideas and developing auspicious strategies for diagnosis and treatment.

Bodour Salhia, associate professor for translational genomics at the Keck School of Medicine and co-leader of the cancer center’s Genomic and Epigenomic Regulation Program, is spearheading projects on liquid biopsies for breast and colon cancer and plays a critical role in the Moonshot grant.

Alan Wayne, associate director for pediatric oncology at the USC Norris cancer center and professor of pediatrics at the medical school, is working on next-generation immunotherapies to treat pediatric blood cancers while also exploring treatments that help the body’s own immune system fight the cancer attacking it.

Lenz and Steve Kay, University and Provost Professor of Neurology, Biomedical Engineering and Biological Sciences at the medical school, are leading a drug development project targeting molecules in circadian pathways that regulate humans’ sleep-wake cycles, an inventive approach that turns the body’s circadian rhythm against cancer.

And in May, Preet Chaudhary, Bloom Family Chair in Lymphoma Research, professor of medicine and director of the Blood and Marrow Transplant and Cell Therapy program at USC Norris, received a $5.8 million grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine to develop next-generation cell therapy for prostate cancer.

“We need continuous scientific inquiry and continuous scientific breakthroughs. That’s what will lead the way,” Kuhn says.

Taking Aim at Cancer

Among the nation’s major research universities, USC is particularly well-situated to lead the battle against cancer.

The university hosts active and energized research programs driven by inquiry, rooted in purpose and fostering accessibility and equity. There are, for instance, research efforts studying prostate cancer in African Americans and breast cancer in Hispanics.

Many research projects, meanwhile, crisscross schools and colleges in the USC ecosystem and feature basic scientists working alongside clinical scientists. At the USC Michelson Center, researchers from biology, medicine, engineering, computer science, chemistry and even the humanities collaborate on projects devoted to improving the lives of those who have cancer.

Our secret power at USC is that we function as a community.

Peter Kuhn

“Our secret power at USC is that we function as a community,” says Kuhn, adding that USC researchers are not only receptive to interdisciplinary work but intentionally prioritize such collaboration. “The Trojan family concept gives us agility, and our work is universally aligned to improving patient outcomes.”

Additionally, USC’s robust infrastructure provides researchers critical access to cutting-edge resources that empower them to probe intriguing questions and generate new knowledge. The USC Norris cancer center, for instance, is a global leader in molecular characterization and is well-known for personalized clinical trials.

“The Norris cancer center has significant strength dealing with diverse patient populations, and this gives us incredible insights into treatments, outcomes, efficacy and interventions,” Lenz says.

Finally, USC boasts one of the most diverse patient populations in the United States and, even more, thoughtfully designed outreach programs to broaden patient representation.

“USC Norris cancer center is a national leader in research to reduce cancer disparities,” says Caryn Lerman, USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center director and the H. Leslie and Elaine S. Hoffman Chair in Cancer Research. “Our innovative community outreach and engagement programs will benefit greatly from the discoveries emerging from USC’s Cancer Moonshot program.”

Partnerships with industry, pharma, health care companies and L.A.’s swelling biotech scene further strengthen USC’s ability to fuel productive cancer research. USC and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center received the U.S. Department of Defense’s first Virtual Cancer Center Director Award in 2021 to launch the Convergent Science Virtual Cancer Center. Experts at the center will advise emerging scholars from diverse research backgrounds and institutions in pursuing scientific advancements in cancer.

“We are well-positioned to be collaborators of the highest level and are aligned to have impact,” says Keck School of Medicine Dean Carolyn Meltzer.

In fact, Meltzer promises more ambitious research, more interdisciplinary collaboration within USC and with external partners, more diversity in trials and genetic testing, deeper community engagement to enroll more patients in clinical and translational research and continued investments in infrastructure to propel the University’s ambitious efforts.

To Meltzer’s point, the Keck School of Medicine and the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center recently teamed with Children’s Hospital Los Angeles to open a Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) facility at the cancer center. The new facility will enable scientists from various disciplines to collaborate on the study, development, manufacturing and testing of cell-based treatments for a range of diseases and disorders.

“We want to grow a critical mass of cancer researchers and really challenge ourselves because if we don’t challenge ourselves, we won’t succeed,” Meltzer says. “We’re prepared to think bigger and bolder because we know that’s what beating cancer demands.”

And it is what patients like Victor Perez need.