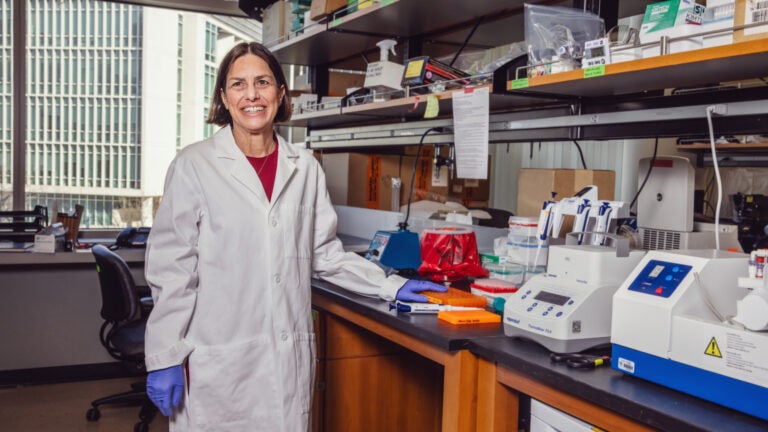

Marlena Fejzo of the Keck School of Medicine of USC has been named one of Time magazine’s 2024 “Women of the Year.” (Photo/Christina Gandolfo)

USC geneticist Marlena Fejzo named one of Time magazine’s 2024 ‘Women of the Year’

The recognition follows the Keck School of Medicine professor’s recent study that showed that a hormone produced by the fetus triggers nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.

USC geneticist Marlena Fejzo, whose discovery of the cause of morning sickness in pregnancy brought international attention to her work, is one of Time magazine’s 2024 “Women of the Year,” the publication announced Wednesday.

The recognition follows Fejzo’s recent study in Nature that showed that a hormone produced by the fetus — and the mother’s sensitivity to it — triggers nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.

Up to 80% of pregnant women experience morning sickness, more accurately known as pregnancy sickness since it can occur at any time of day. Another 2% are affected by a severe form called hyperemesis gravidarum, or HG, which can cause dehydration, weight loss, electrolyte imbalances and hospitalization.

“Dr. Fejzo’s persistence in understanding HG, and her exceptional research, has advanced our understanding of the biology of HG, which is information that will be used to improve health outcomes for both mothers at risk and their children,” said Christopher Haiman, director of the Center for Genetic Epidemiology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Fejzo’s life’s work

Fejzo, who joined Haiman’s Center for Genetic Epidemiology last year, endured HG herself. For months in 1999, pregnant with her second child, she suffered intense nausea, unable to keep anything down. As she literally starved and became too weak to stand, her doctor floated theories about the cause: It was psychological, a bid for sympathy from her husband or a way to get attention from her parents.

At 15 weeks, she lost the pregnancy.

Finding the cause of her condition became her life’s work.

Despite the severity of the condition — which includes the potential for maternal death — few scientists study it, and, historically, funding is difficult to find. The National Institutes of Health has funded only six hyperemesis studies since 2007. Fejzo, whose day job at UCLA at the time was studying ovarian cancer, chipped away at the HG puzzle during her evenings and weekends.

A major breakthrough

A breakthrough came when the 23andMe DNA testing company agreed, at Fejzo’s request, to include a few questions about hyperemesis in a survey. A few years later, she worked with the company to scan the genetic data of more than 50,000 research participants for genes associated with pregnancy sickness.

The results pointed to a specific gene, one that encodes a hormone called GDF15.

Subsequent work suggested two possible solutions for pregnancy sickness: a treatment that could lower levels of the hormone GDF15 during pregnancy, or a preventive effort that would involve exposing the woman to the hormone before pregnancy.

What’s next? Fejzo is applying for funding to test whether metformin, a drug that increases GDF15 levels and could thus “prime” the patient, could be taken prior to pregnancy and prevent or lower the risk of HG.

A newly formed company, Materna Biosciences, recruited Fejzo as its chief scientific advisor as it develops a GDF15-based drug for HG. Several such drugs are already in clinical trials for cachexia, a condition that causes severe weight loss in patients with cancer.

Fighting bias and looking for a cure

Fejzo is pleased by Time’s “Women of the Year” designation, but she mostly hopes to raise greater awareness about the condition — and find better treatments or a cure.

“There continues to be bias. I spoke to a doctor this week who has a patient hospitalized,” Fejzo said. “Besides him, the whole rest of the team dismissed her inability to eat as depression. As soon as they gave her steroids, her nausea and vomiting lifted, she ate, and immediately her mood improved.

“I hope the recognition from Time inspires more women to go into science because hyperemesis is not the only condition that’s under researched,” Fejzo said. “We just need more women scientists out there.”