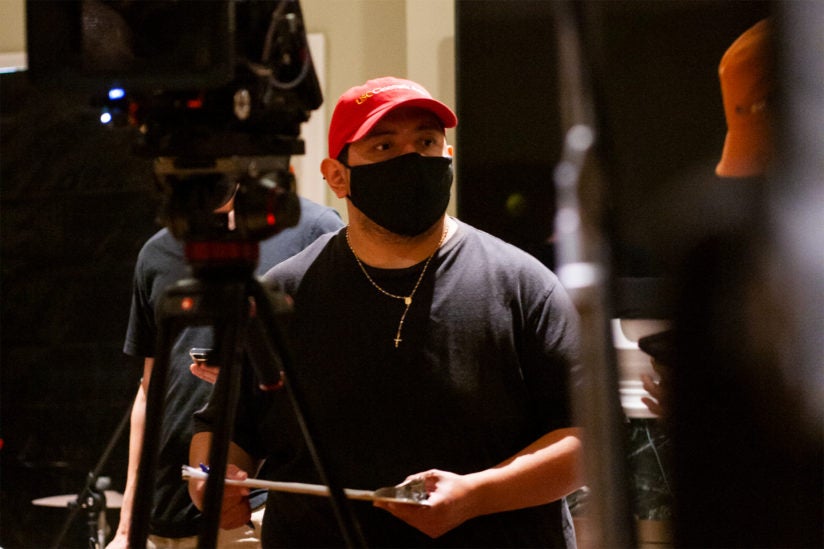

USC School of Cinematic Arts graduate students worked with Jeremy Kagan on a COVID film. (Photo/Courtesy of Jeremy Kagan)

Watch faculty and students’ video clips that encourage COVID vaccinations

Multiple USC schools joined forces with the Vaccinate L.A. team to reach out to specific communities in Los Angeles via research-proven storytelling.

Jeremy Kagan knew he and his fellow Trojans had to do something.

“Communities surrounding our campuses in South Los Angeles and East Los Angeles were getting vaccinated at lower rates,” said Kagan, a professor who teaches graduate courses in directing at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

The internationally recognized director, writer and producer of feature films and television was determined to find out why these communities were hesitant to get vaccinated and hoped he could change their minds.

Change making is kind of his thing.

Kagan is the founder of the USC Change Making Media Lab, which specializes in developing and creating entertainment education that emphasizes the values of narrative dramas and comedies to successfully motivate behavior change.

“My interest is to see how film can be used to shift awareness and change behavior,” he said. “Facts inform but stories transform.”

At that point, Kagan was approached by Sheila Murphy — and old friend and colleague as well as a professor of communication at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism — and the Vaccinate L.A. team to make films that would encourage vaccinations.

(Photo/Courtesy of Sheila Murphy)

“From a public health perspective, this pandemic is the crisis we’ve been preparing for our entire careers,” Murphy said. “And based on our prior work, we knew that narrative and storytelling were powerful tools.”

But since it was, after all, a health crisis, Murphy and Kagan turned to their colleagues on the USC Health Sciences Campus.

“This pandemic, it’s a team sport. There’s no one group, one person or one discipline that’s really going to be able to get us where we need and want to be,” said Michele D. Kipke, professor of pediatrics and preventative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “It’s all hands on deck, everybody coming together.”

Kipke also serves as the co-director of the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute at USC.

“At the start of the pandemic, having that infrastructure in place allowed us to quickly jump on this,” she said. “With that institute, we were actually able to make a hard pivot and just really focus.”

The importance of tailoring messaging for specific communities

Aside from the lifesaving work already being done at USC’s hospitals and research labs, the institute quickly mobilized to fight the pandemic in a myriad of ways.

“At first, we developed community partnerships with educational offerings,” Kipke said. “Then we moved to a multimedia strategy that included the health-and-art campaign Stay Connected L.A., which engaged local artists to develop art that would resonate with the community. These messages were placed on billboards, bus benches and big banners.”

(Photo/Courtesy of the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute)

Next came Vaccinate L.A., which is a joint effort between USC, multiple hospitals and the community to increase access to COVID vaccines for Los Angeles residents.

However, Kipke said the vaccination campaigns proved to be ever-evolving due to the mutating virus, confusing recommendations and an avalanche of misinformation, which resulted in waning vaccination rates in certain areas of Los Angeles.

“We now have different groups that have decided for one reason or another not to get vaccinated,” Kipke said. “We quickly realized that we needed culturally tailored messages, with the right messengers and the right strategies for reaching different specific segments of the population.”

Kagan suggested making two short films, one for the Latinx community and one for the African American community, to confront and combat vaccine misinformation.

“I’d supervise, but I wanted our students to represent their communities,” Kagan said. “They would know best what was creating the vaccine hesitancy.”

Two short films encourage vaccinations within the Black, Latinx communities

Roughly 40 graduate students for USC Cinema joined forces to produce, write and direct two short films to promote vaccination within their communities while countering misinformation.

While Kagan oversaw the production, Murphy supervised the messaging.

“We held 30 focus groups to understand what the issues were surrounding vaccine hesitancy in the African American and Latinx communities in South and East Los Angeles,” Murphy said. “The feedback from these communities revealed that there were six key factors underlying vaccine hesitancy, the main being the myth that the COVID vaccine might lead to infertility. This is nothing new; it’s a very common myth associated with many vaccines.”

(Photo/Courtesy of Jenniffer González Martinez)

Murphy worked closely with the writers to ensure that these misinformation-correcting messages were integrated into both scripts before production on the two films began.

Graduate students Santos Herrera and Jenniffer González Martinez both worked on the Latinx film, Of Reasons and Rumors. The English and Spanish versions of the film follow a tight-knit Latino family in East L.A. who disagree about the importance and safety of the COVID vaccination.

Martinez, who was the scriptwriter, said she felt the weight of every potentially lifesaving word she wrote.

“When I was writing, I was thinking, ‘You have the power to create a feeling, to make them feel and make them think,’” she said. “My script may not save the world, but it may save somebody.”

That somebody could be someone closely connected to the making of the film, like the family of director Herrera.

(Photo/Courtesy of Nancy Boyd)

“The impact was both professional and personal for me,” he said. “My sister was hesitant to get the vaccine. After I showed her the film, she went and got vaccinated.”

MaryLanae Linen, who is a second-year graduate student, worked on the African American film, Happy Birthday, Granny. It follows an African American family in South L.A. celebrating their grandmother’s birthday, except some family members are hesitant about getting their shot.

Linen credits Kagan for the authenticity of the film’s messaging.

“He tapped Black and Brown filmmakers to create content that is directed towards us,” Linen said. “If you watch it, the language is written by a Black person for Black people. Just like the Latinx film and the things they talked about, only they really know.”

Previous short film showed success in emphasizing cervical screenings

The films were finished in July and posted on the VaccinateLA website. They were an instant hit among the targeted communities, which came as no surprise to the films’ creators.

“We’d used narrative to successfully affect behavior before, so we know it works,” Murphy said. “We also tested the films on 600 unvaccinated Latinx and African American people and so we have the research to back up the efficacy of both films in terms of increasing the intent to be vaccinated.”

The careful creating and testing of health messages is Murphy’s passion. In 2009, Murphy approached the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct a randomized, controlled trial comparing the relative efficacy of narrative and non-narrative campaigns in changing behavior.

Trained in experimental methodology, Murphy said she felt especially prepared to design and conduct this comparative study.

“The NIH had never done a comparison like this before because, at the time, the federal government wasn’t using narratives or stories to convey medical information,” she said. “I felt qualified to do it because not only am I an expert in persuasion but I am also a public health researcher and social psychologist.”

In 2011, Murphy and Kagan produced two 11-minute films — a narrative, Tamale Lesson, and a non-narrative, It’s Time. Both films contained the same 10 facts designed to encourage at-risk women to get cervical cancer screenings.

In a randomized controlled trial of 900 women — 300 African American, 300 Latinx and 300 European American women – women were randomly sent either the narrative or non-narrative film. The results revealed in general the narrative was more effective in convincing women to have a Pap test. This was particularly true among the Latinas in the study who identified with the largely Latina cast of Tamale Lesson. In fact, by the six-month follow-up the Latina participants who viewed Tamale Lesson went from having the lowest rate of cervical cancer screening (32%) to having the highest (82%).

Tamale Lesson received wide attention from the medical community and the comparative study was published in the American Journal of Public Health. A decade later, they hoped to replicate that successful uptick in cervical screenings with an increase in COVID vaccinations.

“We decided to put the band back together,” Murphy said.

Short films promoting vaccinations have even reached the White House

The “band,” so to speak, consisted of Murphy, Kagan and Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, a professor in preventative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“A number of years ago, the three of us had worked on a health campaign together which ended up being very effective,” Baezconde-Garbanati said. “We all have our expertise in things.”

One of her areas of expertise is securing grant money for vital projects, which she was able to do for the two COVID films through the Keck Foundation. The funds were used to hire the cast and crew, rent equipment, secure filming locations and finance post-production.

But once the films were finished, something very unexpected happened.

“The White House saw them, and were blown away,” Kipke said. “And now the world is seeing them.”

(Photo/Courtesy of the Keck School of Medicine)

Baezconde-Garbanati is a member of the White House’s COVID-19 Community Corps, which serves to amplify vaccine messaging within communities and combat skepticism and misinformation. She showed the films to the Community Corps members.

In addition, the COVID films have been displayed by the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health on all of its online forums and in its newsletter, which is read by the deans of schools of public health across the country.

Also, the Latinx film is being promoted by the National Hispanic Alliance for Health to its 15 million members.

“It has brought the best of USC together from multiple schools and units with a shared vision and singular purpose: to save lives,” Kipke said. “And we are accomplishing that. We are saving lives.”

Currently, the COVID films are being shown in at least 38 cities throughout the U.S., as well as Guatemala and Canada.

“Coming together as a university, as one body, to confront this disease is our armor — USC’s Trojan armor,” Baezconde-Garbanati said. “There is nothing stronger.”

Already in the works is a third short film to promote child vaccinations.