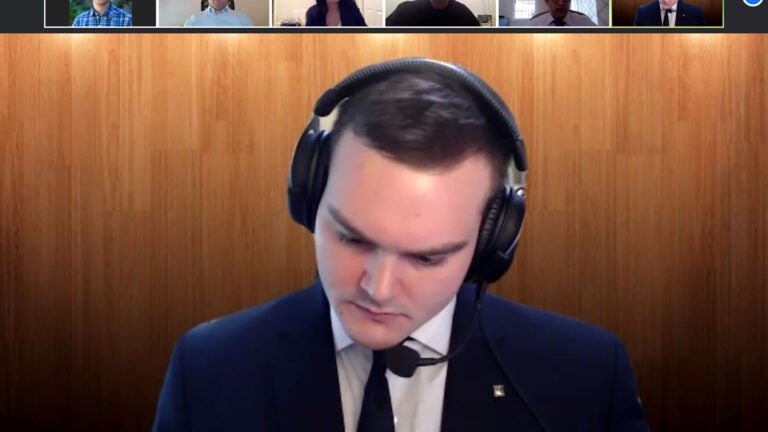

Hunter Collins, an intelligence and cyber operations major at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, testifies in a mock trial involving digital espionage. (Image/Courtesy of Joseph Greenfield)

To test their cybercrime knowledge, USC students take witness stand in virtual courtroom

With COVID-19 cyberscams rampant, industry pros from firms worldwide watch as USC digital forensics students show their crime-fighting smarts in front of a real-life judge online.

An intern at a defense firm gains access to top-secret information, steals it and tries to sell it to a foreign power.

Called in to investigate as a cybercrime expert, you must carefully piece together the plot using evidence from the intern’s laptop, records of online video calls and other digital information.

Then you step into the hot seat: the witness box in a criminal courtroom. Attorneys interrogate you relentlessly as you testify, searching for weaknesses in your knowledge as a judge watches solemnly from the bench.

Thirteen USC students faced that precise scenario this month. They took the stand as part of the capstone project in their advanced digital forensics class at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering. In years past, students in the class traveled to a real courtroom, but this year the COVID-19 pandemic pushed them to a digital venue: a videoconference on Zoom.

But the students felt just as much pressure as ever, said Joseph Greenfield, an associate professor of information technology practice who has held the mock trial each May for the past 12 years.

He even brought in two seasoned prosecutors — from the cybercrime divisions of the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office and U.S. Attorney’s Office — to grill the expert witnesses. And a retired L.A. County Superior Court judge presided from his home office, complete with black robes.

“Let me tell you, the attorneys did not hold back,” Greenfield said. “They were there to win, and you could tell by the questions they were asking and how they asked them. Anyone in law enforcement who watched it knows, these attorneys came to play.”

Students showcase cybersecurity skills for potential employers during mock trial

Dozens of industry professionals from tech firms, consulting companies and cybercrime investigation agencies also watched carefully.

Although perhaps not as intense as a real-life court case, the exercise had high stakes. Perform well, and the students might get a job offer on the spot. Past graduates drew interest from the FBI, U.S. Secret Service, Apple and major consulting and investigative firms.

“It’s a great way to show off talent,” Greenfield said. “Every year, we have 30 to 40 guests from across the L.A. area. The biggest advantage this year is we had worldwide attendance. We had people from Microsoft logging in from all over the world.”

Demand is high for recent graduates with expertise in digital forensics — a field of science that focuses on investigation and recovery of digital material.

And for good reason: Cybercrime is estimated to cost $6 trillion a year by 2021, with a ransomware attack against businesses occurring every 11 seconds, according to a private research firm. Another analysis found the costs of identity fraud alone reached $16.9 billion in 2019.

“There are COVID-related spam and cyberscams going on right now,” Greenfield said. “You can be anywhere in the world and break into any company here in the U.S. Global cybercrime has eclipsed the drug trade. It’s far more lucrative, it’s easier to do and there’s less jail time. You’re going to go to jail for a lot longer for smuggling cocaine than for smuggling a flash drive with 100,000 Social Security and credit card numbers.”

And cybersecurity is a booming business — the global market is worth an estimated $173 billion.

“At last check, there were more than a million open jobs in the U.S.,” Greenfield said. “Starting salaries since 2010 have increased by $5,000 per year on average, so graduates are looking at between $78,000 to $110,000.”

USC’s cybersecurity curriculum is well regarded, said Greenfield, who earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees in computer engineering and computer science at USC Viterbi. Two years after he returned to his alma mater as an instructor in 2006, he created the courtroom capstone project, which has since become a rite of passage for students in the digital forensics program.

“This mock trial is extraordinarily memorable for our students,” said Erik A. Johnson, USC Viterbi’s vice dean for academic programs and professor of civil and environmental engineering. “It gives them an opportunity to showcase what they’ve learned over their whole time at USC. And for a lot of our students, it leads directly to jobs.”

As mock cybercrime testimony shifted online, instructor found ways to recreate intensity

When it became clear by late March that classes would be held online for the rest of the spring semester, Greenfield scrambled to devise an alternative to his usual in-person exercise — typically held in a downtown Los Angeles or Santa Monica courtroom.

“Luckily, one of the judges we had used previously and who retired was interested in helping us out,” he said. “A former prosecutor who’s pretty well-versed in Zoom was ready to help out, too. One of our part-time faculty who is also an L.A. County prosecutor and is used to teaching on Zoom said, sure, let’s try this.”

Students each faced 10 minutes of questioning. First, the prosecutor tried to bolster the case against the cybercriminal. Then the defense attorney tried to poke holes in the students’ arguments and evidence.

Johnson said although a videoconferencing platform doesn’t have the gravity and grandeur of a courtroom, this year’s trial still felt like a serious affair.

“The judge and the two attorneys did a very good job in trying to make it as lifelike as possible,” he said. “They were pointed in their questions and acted toward the witnesses the way they would have in a courtroom. Given the environment, this was a very good replica of what we’d do in person.”

To enhance the suspense and anxiety, students couldn’t enter the virtual courtroom until their turn to testify, so they couldn’t watch their peers. Greenfield relied on his own experience to create a realistic courthouse atmosphere — he has written court statements and prepared to testify as a digital forensics expert with L.A.-based investigative firm Maryman & Associates.

He acknowledged his students faced unique challenges this year, particularly not being able to work alongside one another in person as they investigated the mock cybercrime. But despite obstacles created by the coronavirus pandemic, Greenfield said he is impressed with his students’ resilience and ability to adapt.

“They’ve performed very admirably this year,” he said. “It’s been unlike any other semester I’ve ever taught, and the students have really stepped up.”