How the Pandemic Changed Museums Forever (or Did It?)

Turns out that “Botticelli on Zoom” and art talks from the couch might change the way Americans get their culture fix.

The exhibition “We Are Here: Contemporary Art and Asian Voices in Los Angeles” opened at the USC Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena to great uncertainty. Just two days earlier, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. As fear spread, so did a rising tide of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia.

The museum’s show featured seven L.A.-based female artists of Asian Pacific heritage whose artwork — such as Phung Huynh’s portraits of Southeast Asian refugees on pink donut boxes and Ann Le’s photomontages of her Vietnamese refugee family — drew on their experiences in immigrant communities recovering and starting anew after war trauma. It stayed open for only three days before the museum closed its doors.

“It was heartbreaking,” says USC Museums Interim Director Bethany Montagano, who is also director of the USC Pacific Asia Museum. “We knew that the messages of that exhibition and what these really amazing female Asian American contemporary artists had to say were really important to the AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] community that was in pain due to anti-Asian hate further unveiled in the wake of COVID.”

Not knowing when — or if — the museum could welcome back visitors, Montagano and her team of 15 asked themselves: “How can we take what we do at the museum outside of the four walls and deliver a relevant and resonate experience to people’s homes?”

Art leaders across the country and the world wrestled with the same question. Pandemic closures stretched on for weeks and months, shuttering exhibitions and bringing ticket sales to a standstill.

The upshot? Art institutions shifted their creativity into high gear, finding new and innovative ways to engage with the public. Virtual art museum tours took hold, and the way we view and talk about art may never be the same.

Virtual Museum Tours Bring Galleries Home

Though the technology to create virtual exhibitions existed prior to the pandemic, many museums were slow adopters. “It’s almost antithetical to promote digital programs because the whole point of a museum is to come see the work in real life,” says Eunice Lee ’05, an art history alumna who is now the director of strategic partnerships and events at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

The lack of physical access during the shutdown “forced the museum field to innovate in ways that were surprising,” Montagano says. To showcase “We Are Here” virtually, The USC Pacific Asia Museum tapped into software called Matterport, which uses 3D technology to make immersive replicas of physical spaces. Montagano says Matterport recreates the essence of an in-person experience by allowing online users to recreate walking through an exhibition gallery. They can stop at artwork along the way, listen to audio clips and watch in-gallery videos.

The museum’s website traffic spiked after the online tour opened. People visited from all over the world. “It democratized the exhibition and its messages, opened them up to a broader audience and made our important work much more accessible,” Montagano says.

Related events, such as discussions of refugee narratives and women’s issues, also moved online, where attendance skyrocketed. While in-person programs typically attract 30 to 40 people, upward of 800 people from across the globe joined these virtual conversations.

Montagano believes that the bump in attendance reflects not only increased access but also people’s eagerness to discuss social justice topics in the wake of protests that erupted around the country following George Floyd’s death in 2020. The innovations, she says, enabled the USC Pacific Asia Museum to take a “really bold, authentic and daring stance that we were not going to be neutral, that we were going to use art in order to facilitate brave and courageous conversations around social issues directly affecting our campus and surrounding AAPI communities.”

Museums Keep Art Connected to Community

Less than a mile from the USC Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena stands the nonprofit Armory Center for the Arts. The pandemic disrupted use of the space as a hub where artists and art enthusiasts forge connections. “As a mid-size arts organization, engagement with our close-knit community is something that we count on when planning exhibitions and programs,” says Heber Rodriguez ’10, MA ’15, the Armory’s exhibition program production manager and a graduate of the USC Roski School of Art and Design.

So Rodriguez and his team turned to tech to preserve these intimate interactions. They found ways to translate interactive elements of the exhibition “Tanya Aguiñiga: Borderlands Within/La Frontera Adentro” into virtual experiences. The exhibition explored immigration and identity politics at the U.S.-Mexico border. Aguiñiga had planned several in-person performances in which she would weave an art piece that spanned the entire gallery, but Armory broadcast the weaving performance on Instagram and Facebook instead.

The gallery installation “You Are Invited/Estás Invitado” encouraged visitors to write messages on slips of paper and then drop them into a box. Aguiñiga planned to bury the box at the foot of the border wall on the Mexico side. Visitors to the exhibition’s webpage could submit a secure, anonymous message online to be included, replicating the activity’s intimacy.

The Armory also filmed and posted a video of Aguiñiga walking through the gallery and explaining each piece in the exhibition. To Rodriguez’s surprise, the video drew international viewers. At a time when the U.S.-Mexico border was closed to all but essential business, the exhibition’s messages floated across geographical barriers.

Curating Art for the Web

The pandemic interrupted access to art in public spaces, too. Nateene Diu MA ’16 — an arts associate in the public art division of L.A.’s Department of Cultural Affairs at the time — had been overseeing an installation in one of the terminals at the Los Angeles International Airport when the pandemic halted her work.

Diu and other staff couldn’t meet to mount exhibitions and unveil new murals, sculptures and other public art. At the same time, the concept of “public spaces” changed quickly as work and social lives moved online. “Public art necessitated a change from us,” says Diu, a USC Roski alum.

Along with the L.A. City Council, the division established an emergency economic relief fund for creators struggling to make a living during the pandemic. Some 250 artists — working across photography, illustration, music, film, dance, makeup and more — received awards to create works that they submitted to DCA digitally.

Diu and her co-curator shaped the submissions into “Reimagine Public Art,” the first online-only exhibition created by the public art division and the Department of Cultural Affairs’ main office. The exhibition explores themes that emerged during the lockdown: collapsing work and home, adapting art practice to new constraints and employing art as a tool for wellness and social justice.

The project pushes the boundaries of public art beyond static works like murals and sculptures toward hybrid and digital forms that blur public and private spaces. Diu points to examples like Dexter Story’s “Whose Streets? Protest Sound Image, 2020” — recorded on an iPhone during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hollywood — and David Ralicke’s “39th Street Rooftop Lament and Meditation,” a 24-hour time-lapse video filmed from the artist’s South Los Angeles home set to music he composed, performed and recorded there.

Diu, now a junior advancement associate for membership and events at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, says the experience has left a lasting impact. “We can’t just go back to putting public art in a very neat box because the ‘public’ in public art has changed.”

Moving Scholarship Forward

Art historian Rika Hiro MA’ 01, PhD ’16 has always emphasized to her students the importance of seeing the art objects they study in person. The 20th-century Japanese art expert, who taught art history as a postdoc at the USC Dornsife College of Arts, Letters and Sciences from 2017 to 2020, thought little of viewing art online.

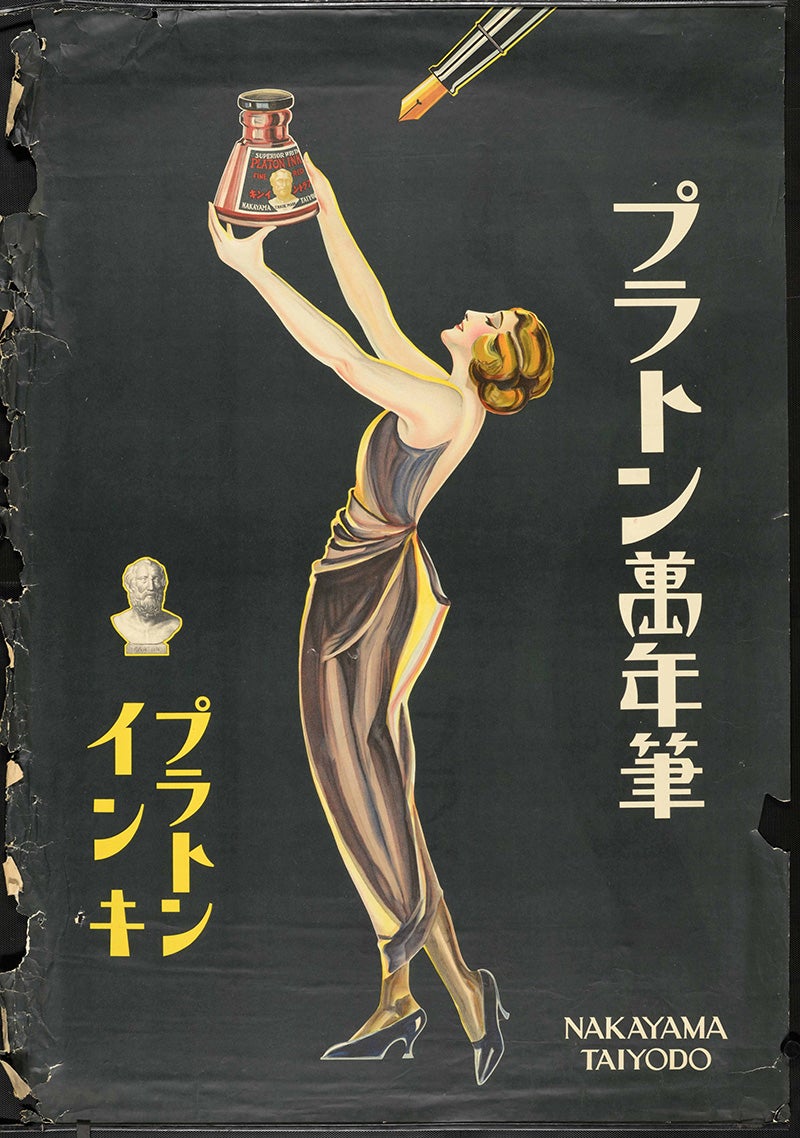

But when pandemic closures in spring 2020 blocked her undergraduate students from mounting a planned exhibition at Doheny Memorial Library, Hiro turned to an online platform to keep the project afloat. Students had already completed original research on USC Libraries’ rare collection of pre-World War II Japanese posters to be featured in the exhibition. Hiro wanted their work to be seen.

With the help of library curator Anne-Marie Maxwell and Japanese studies librarian Rebecca Corbett, Hiro and her students used innovative web-based publishing software called Scalar, developed by USC researchers with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The students created the online-only exhibition “Underpinning History: Japanese Posters in the Age of Commercialism, Imperialism and Modernism.” Scalar allowed students to create a flexible structure akin to a media-rich online “book” so that visitors can move through content and explore it however they like — not just from front to back.

“I finally realized the benefit of working online,” Hiro says. Without the physical limitations of a gallery space, the class nearly doubled the number of posters included in the exhibition. Among them were damaged posters that are too fragile to display physically. Additionally, there was room online to include longer text descriptions written by students, with embedded links to supplementary information. And while the physical exhibition would have closed after a couple of months, the online exhibition can endure.

Hiro was especially delighted by how the Scalar exhibition broadened the reach of her students’ scholarship to national and international audiences. She received inquiries from scholars and curators who are interested in coming to view USC’s Japanese poster collection in person, bringing the project full circle.

The Digital Future of Art is Now

In cities like New York and Seattle, where museums reopened months before those in Los Angeles, art lovers still want to view works in the flesh — maybe even more than before the pandemic.

“One thing we learned when we reopened the museum was just how hungry people were to actually be in the presence of original works of art,” says Theresa Papanikolas ’86, the Ann M. Barwick Curator of American Art at the Seattle Art Museum, which welcomed visitors back in March. The USC Dornsife graduate saw that with “Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle,” an exhibition she co-curated that explores how women and minorities shaped narratives in American history. Visitors lingered in the gallery much longer than usual.

But many of the digital innovations that emerged during closures will remain, experts say.

Montagano believes that the public’s enthusiastic embrace of 3D tours and online programs shows that people want options to engage with art free of geographical and financial constraints. During the shutdown, museums “created unprecedented access … and we want to keep it that way,” she says.

Going forward, she adds, USC’s museums will prioritize a hybrid exhibition model, with in-person and virtual experiences. Likewise, Rodriguez and Diu both believe digital engagement will remain an important component of their community art programming. And Hiro plans to continue to use online tools in her teaching and scholarship.

The museum visit of the future will likely be one that straddles both in-person and online realms. The Whitney in New York, which reopened last September, has pursued that model by continuing to offer virtual programs such as artist talks. “We noticed a lot of times when people participate in these kinds of virtual programs, they end up showing up in real life, too,” Lee says. Virtual can’t replace in-person experiences, but it can become a complement to future visits.

We can leverage the coalescing power of art and act as agents of positive social change.

Bethany Montagano

Pandemic closures showed museums the potential of expanding access to a greater array of artists and art enthusiasts, even when COVID-19 becomes a memory.

Online exhibitions like “Reimagine Public Art” allow for so many more voices, both in quantity and in diversity, than typical in-person exhibitions, Diu says. And virtual programs like the Armory’s series “Active Voice: Conversations at the Intersection of Community, Art, and Social Justice,” which launched in February, broaden impactful discussions of pressing issues.

The changes wrought by the pandemic demonstrate that museums have the potential to be relevant, socially engaged spaces in our communities, Montagano says. “We can leverage the coalescing power of art and act as agents of positive social change.”