People can be hardheaded about their political beliefs. (Illustration/iStock)

Which brain networks respond when someone sticks to a belief?

When political beliefs are challenged, a person’s brain becomes active in areas that govern personal identity and emotional responses to threats, USC researchers find

A USC-led study confirms what seems increasingly true in American politics: People are hardheaded about their political beliefs, even when provided with contradictory evidence.

Neuroscientists at the Brain and Creativity Institute at USC said the findings from the functional MRI study seem especially relevant to how people responded to political news stories, fake or credible, throughout the election.

“Political beliefs are like religious beliefs in the respect that both are part of who you are and important for the social circle to which you belong,” said lead author Jonas Kaplan, an assistant research professor of psychology at the Brain and Creativity Institute at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “To consider an alternative view, you would have to consider an alternative version of yourself.”

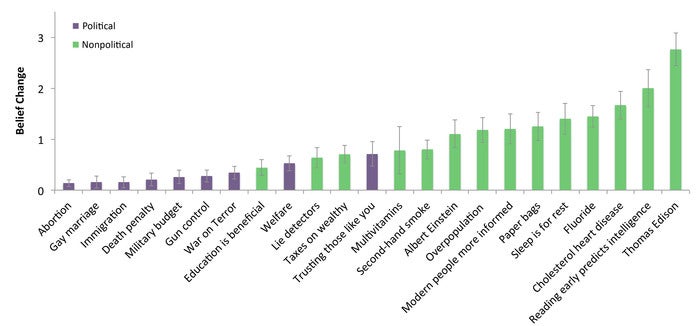

To determine which brain networks respond when someone holds firmly to a belief, USC neuroscientists compared whether and how much people change their minds on non-political and political issues when provided counterevidence.

They discovered that people were more flexible when asked to consider the strength of their belief in non-political statements — for example, “Albert Einstein was the greatest physicist of the 20th century.”

But when it came to reconsidering their political beliefs, such as whether the United States should reduce funding for the military, they would not budge.

“I was surprised that people would doubt that Einstein was a great physicist, but this study showed that there are certain realms where we retain flexibility in our beliefs,” Kaplan said.

Challenging beliefs

The study was published on Dec. 23 in the Nature journal Scientific Reports. Study co-authors were Sarah Gimbel of the Brain and Creativity Institute and Sam Harris, a neuroscientist for the Los Angeles-based nonprofit Project Reason.

For the study, the neuroscientists recruited 40 people who were self-declared liberals. The scientists then examined through functional MRI how their brains responded when their beliefs were challenged.

During their brain imaging sessions, participants were presented with eight political statements that they had said they believe just as strongly as a set of eight non-political statements. They were then shown five counter claims that challenged each statement.

Participants rated the strength of their belief in the original statement on a scale of 1-7 after reading each counter claim. The scientists then studied their brain scans to determine which areas became most engaged during these challenges.

Participants did not change their beliefs much, if at all, when provided with evidence that countered political statements such as, “The laws regulating gun ownership in the United States should be made more restrictive.”

But the scientists noticed the strength of their beliefs weakened by one or two points when challenged on non-political topics, such as whether “Thomas Edison had invented the light bulb.” The participants were shown counter statements that prompted some feelings of doubt, such as “Nearly 70 years before Edison, Humphrey Davy demonstrated an electric lamp to the Royal Society.”

Thoughts that count

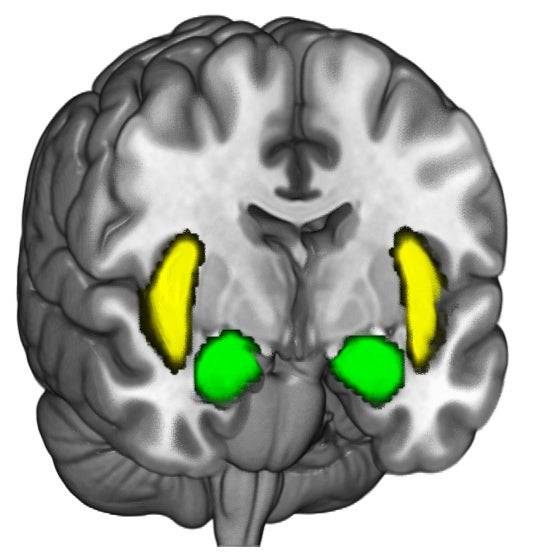

The study found that people who were most resistant to changing their beliefs had more activity in the amygdala (a pair of almond-shaped areas near the center of the brain) and the insular cortex, compared with people who were more willing to change their minds.

“The activity in these areas, which are important for emotion and decision-making, may relate to how we feel when we encounter evidence against our beliefs,” said Kaplan, a co-director of the Dornsife Cognitive Neuroimaging Center at USC.

“The amygdala in particular is known to be especially involved in perceiving threat and anxiety,” Kaplan added. “The insular cortex processes feelings from the body, and it is important for detecting the emotional salience of stimuli. That is consistent with the idea that when we feel threatened, anxious or emotional, then we are less likely to change our minds.”

He also noted that a system in the brain called the default mode network surged in activity when participants’ political beliefs were challenged.

“These areas of the brain have been linked to thinking about who we are, and with the kind of rumination or deep thinking that takes us away from the here and now,” Kaplan said.

High-level thinking

The researchers said that this latest study, along with one conducted earlier this year, indicate the default mode network is important for high-level thinking about important personal beliefs or values.

“Understanding when and why people are likely to change their minds is an urgent objective,” said Gimbel, a research scientist at the Brain and Creativity Institute. “Knowing how and which statements may persuade people to change their political beliefs could be key for society’s progress,” she said.

The findings can apply to circumstances outside of politics, including how people respond to fake news stories.

“We should acknowledge that emotion plays a role in cognition and in how we decide what is true and what is not true,” Kaplan said. “We should not expect to be dispassionate computers. We are biological organisms.”

The work was supported by the Brain and Creativity Institute at USC and by Project Reason.