Digital Technology Ensures the Lessons of the Holocaust are Never Lost

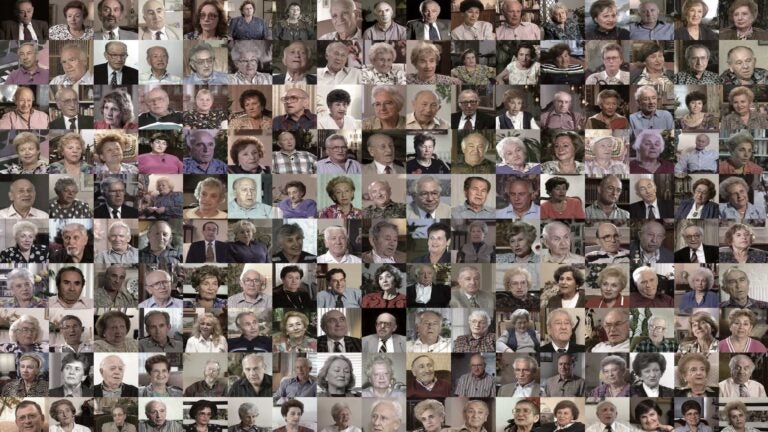

The USC Shoah Foundation painstakingly guards the last remaining voices of the survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust.

Ask Steven Spielberg about his legacy, and the Oscar-winning filmmaker and longtime USC trustee won’t talk about Schindler’s List,Saving Private Ryan or Lincoln. He’ll point to 107,000 hours of unedited, unscripted video shot in the mid-to late 1990s— 52,000 interviews with survivors of and witnesses to the Holocaust, called the Shoah in Hebrew.

Now known as USC Shoah Foundation—The Institute for Visual History and Education, the organization maintains the Visual History Archive, constituting one of the world’s largest audio-visual collections on a single subject. It’s even more expansive than NFL Films.

This year, the Shoah Foundation, started by Spielberg, marks its 20th anniversary. Twenty years, as it happens, is also the age at which video starts to decay.

And there’s the rub: Having painstakingly assembled a breathtaking historical artifact—the voices of tens of thousands of survivors, witnesses and liberators—how do you keep it safe in a race against time? Leave it to Sam Gustman, though even he is no optimist.

“Everything rots,” says Gustman, USC Shoah’s chief technology officer, who joined the project in 1994. “The newer the technology, the faster it rots.” He recites the grim stats: Film, by conservative estimates, lasts 50 years before age-based decay starts to set in. Videotape, 20 years. Hard drives, five years. Data tape, three years. DVDs, two years.

On the fourth floor of the Carol A. Little building, just east of the University Park Campus, Gustman weaves his way through the labyrinth of USC’s central computing facility, home of the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive.

The testimonies, Gustman explains, were captured on what was state-of-the-art technology in the mid-1990s: half-hour Betacam SP videotapes. The collection filled 235,000 of them.

At the peak of production, video crews were taping more than 300 interviews a week. Working from field offices in remote corners of places like Bulgaria and Slovenia, the crews had no way to reproduce the tapes. So they popped the originals into boxes and mailed them to Universal Studios, where the Shoah Foundation had originally set up shop in a couple of trailers.

Miraculously, none of the tapes were lost, though some were damaged. A few arrived completely flattened.

The fix: create “Frankentapes,” reanimated hybrids stitched together from old and new cassette parts.

A robotic tape player then copied every tape in three different formats before the masters were moved into an underground storage facility. Later, the interviews were transferred to motion-picture-industry-standard digital files, a three-year process that cost $8 million.

Still, about 4 percent of the testimonies contained digital glitches—potentially leaving some 12,000 tapes from being seen. USC Shoah technicians—mostly USC Viterbi engineering students—are now combing the testimonies for what experts call signal errors. Second by second, pixel by pixel, these students are filling the digital gaps.

Gustman brings an engineer’s zeal to his work, leaving nothing to chance. With the help of a robot, he makes sure every digital bit of the archive is protected. Two identical copies of the complete archive reside in the university’s main data center, where every night the robot compares hundreds of testimony pairs in search of discrepancies. Any suspect data get dumped automatically. Digital archivists call the process “preservation through migration.”

Word of their expertise gets around. Smaller groups now turn to the institute for assistance in digitizing and indexing their fast-decaying collections. The 1,400 testimonies of the San Francisco-based Jewish Family and Children’s Services, for example, are currently undergoing restoration and preservation at USC Shoah Foundation. They’ll be integrated eventually into the Visual History Archive.

“How do you guarantee that something is going to last 100 years?” Gustman asks. “The only things we have right now that meet this standard are stone and paper. No one’s got a crystal ball. The reason we’re doing preservation through migration is because that’s the best you can do today.”

Should disaster strike, there’s a backup plan. A replica of USC’s self-duplicating archive exists at Clemson University in South Carolina. Eventually, Gustman wants mirror archives on every continent.

“If you really want testimony to be around forever, you have to keep the risk as low as you can,” he says.

Learn more about USC Shoah and watch testimonies at vhaonline.usc.edu and youtube.com/uscshoahfoundation. To help continue the foundation’s work, visit sfi.usc.edu/donate.