Ozempic and similar drugs like Wegovy, Zepbound and Mounjaro are a pop culture phenomenon — but it’s possible that they can change the way public health is managed, as well. (Illustration by Raymond Biesinger)

Obesity and diabetes drugs can catalyze profound changes in your body — and in public health, too

USC experts say anti-obesity drugs have the potential to significantly reduce future health care spending.

Jennifer* had obesity, diabetes, severe acne and excess facial hair — the result of a hormonal disorder called polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS. PCOS is linked to infertility and a host of other issues.

Her doctor, Katie Page, an endocrinologist and associate professor of medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, knew that typical treatment — insulin, daily exercise and dietary changes — offered modest improvement, at best. For Jennifer, Page wanted to try something else: the anti-diabetes drug Ozempic.

In just six months, Jennifer lost 70 pounds. Her diabetes went into remission, and problems with acne and excess facial hair disappeared.

“Patients love it because it’s only administered once a week and the effects are just amazing,” Page says. “It has been so great just to have something that works.”

Thanks to its use by celebrities and its ability to cause rapid weight loss, Ozempic and similar drugs like Wegovy, Zepbound and Mounjaro are a pop culture phenomenon — the subject of tabloid speculation, podcasts and late-night TV jokes.

But behind the hype is a medication that could catalyze profound changes in public health. With 75% of Americans now classified as overweight or obese, according to a recent study in The Lancet, obesity is one of the biggest health challenges facing the country.

“These medications not only benefit patients in terms of the weight loss itself but also clearly improve metabolic function and either ameliorate or even eliminate diabetes,” says Pinchas Cohen, dean of the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. “We are now in a completely new era of managing these conditions.”

“These medications not only benefit patients in terms of the weight loss itself but also clearly improve metabolic function and either ameliorate or even eliminate diabetes.”

Pinchas Cohen, dean of the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology

The economic toll of obesity

By lowering the nation’s staggering obesity burden — as well as rates of associated illness that increase disability and reduce the quality of life — anti-obesity drugs have the potential to reduce future health care spending significantly.

“Obesity is a complicated issue, and one that we, as a society, need to address,” says Anne Peters, a professor of medicine at the Keck School of Medicine and one of the world’s leading diabetes expert and advocates for new care guidelines for the disease. “It can lead to many illnesses in addition to diabetes, such as increases in cancer and heart disease, sleep apnea, joint disease, back pain and huge numbers of other problems. Our bodies aren’t meant to carry that much weight.”

A USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics white paper that chief scientific officer Darius Lakdawalla and colleagues contributed to estimates that Medicare coverage for new obesity treatments could save $175 billion in health care costs in the first 10 years alone. A Goldman Sachs forecast predicts widespread use of the drugs in the United States could boost gross domestic product by 1% as lower obesity-related complications increase workplace efficiency.

“Obesity is a leading risk factor for mortality in the U.S.,” Lakdawalla says. “Our modeling shows that new treatments generate substantial benefits to Medicare and its beneficiaries. Developing strategies for unlocking that value should be a priority for policymakers.”

“Obesity is a leading risk factor for mortality in the U.S. Our modeling shows that new treatments generate substantial benefits to Medicare and its beneficiaries.”

Darius Lakdawalla, chief scientific officer at USC Schaeffer Center

Experience for patients

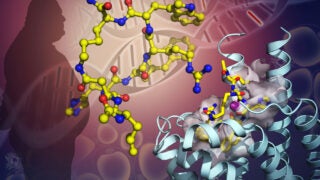

Semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy, mimics a hormone, GLP-1, released in the gastrointestinal tract in response to eating. Tirzepatide, the active ingredient in Zepbound and Mounjaro, also mimics GLP-1 plus another gut hormone known as GIP. They help lower blood sugar by helping the pancreas make more insulin. Patients say the drugs reduce cravings and quiet the brain’s constant “chatter” about food and eating.

Peters says she initially starts patients off with a low dose of weight-loss drugs before increasing slowly because patients tend to experience gastrointestinal side effects early on, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting and constipation.

Weight loss is slow, she says, but patients start feeling full long before they’ve actually lost a lot of weight. Peters advises them to not only eat less but also healthier, with high-quality protein to avoid a loss of muscle mass. She gave an example of a patient who, despite loss of appetite and eating significantly less, maintained the same weight and blood sugar due to an unchanged, unhealthy diet.

“I work with people on healthy nutrition to go along with the fact that they’re not going to feel like eating as much,” Peters says. “It’s all about watching your body, listening to your response and then talking to your health care provider.”

Broad access to the drugs is essential

Christopher Scannell, a physician and postdoctoral researcher at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, says that the intense focus on semaglutide’s anti-obesity effect obscures that the drug is also hugely important for treating diabetes.

“It’s the reason why I’ve been able to get some of my patients off insulin,” Scannell says.

In 2024, Scannell and Dima Qato, an associate professor at the USC Alfred E. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and senior scholar at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, published research about potential inequities in access to the drugs.

Their study, which examined prescription data, found that the vast majority of Ozempic and Wegovy prescriptions were going to people with private insurance — and far fewer going to people on Medicaid or Medicare Part D. Obesity disproportionately affects lower-income communities of color.

“If only certain patient populations get access to these medications — those primarily with private insurance, more generous health plans — then a huge percentage of the U.S. population isn’t getting access to these medications,” Scannell says. “That brings up a very significant equity issue.”

Big-picture solutions

Kayla de la Haye, director of the Institute for Food System Equity at USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, sees immense promise in Ozempic and other drugs like it. But it’s still important to address underlying problems fueling the obesity epidemic.

“For people living in unhealthy food environments — where unhealthy foods are cheap, convenient and accessible, while healthy options are not — their food environment is stacked against them,” says de la Haye, who studies the impact of low-quality food environments on overall health. “We need strong investment to make our food environments healthier.

“These drugs are expensive, and most people will transition off from them at some point. So, we also need to ramp up our investment in big-picture solutions that make it easier for people to start and sustain healthy eating habits.”

*not her real name