CRISPR is a powerful, potentially harmful gene editing technique

CRISPR-Cas9 is a gene-editing technique that enables scientists to disable, replace or modify sections of DNA. It allows for unprecedented precision and speed in the field of genome editing. It has been used to create micropigs to be sold as pets and to try to eradicate HIV infection in humans.

The scientific community is concerned about altering human embryos to create “designer babies,” but some USC experts say that in the United States, CRISPR-Cas9’s use on plants and animals will make waves first. Should these edited organisms be labeled as genetically modified organisms (GMOs)? Questions about environmental consequences, the ethics of consent and public policy will need to be addressed.

Contact: Zen Vuong at (213) 300-1381 or zvuong@usc.edu; Andrew Good at (213) 740-8606 or gooda@usc.edu.

___________________________________________________

We’re not having the right conversation

“The December 2015 call for a moratorium on the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to make heritable changes to the human genome may not be enforceable or practical. The truth is that countries that do not have well-regulated research protocols could allow companies to exploit people’s vanity or desperation and use this technology to engineer human embryos. In such situations, saying let’s not do any germ line engineering is too simplistic. We should instead continue to research how this could be done safely and understand more about the process, while recognizing that society currently does not condone the use of this technology.”

Paula Cannon is a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, where she leads a research team that studies viruses, stem cells and gene therapy. Cannon has been working on the precursor to CRISPR-Cas9, “zinc-finger nuclease editing,” for nine years. She is engaged in a clinical trial that edits DNA in the middle of the CCR5 gene in an effort to produce an HIV-resistant immune system.

Contact: (323) 442-1510 or pcannon@usc.edu.

___________________________________________________

Best medical intentions could lead to ‘designer babies’

“If CRISPR-Cas9 is used on human embryos one day, decision makers will face a dilemma. How do we discern between disease-altering intervention versus aesthetic manipulations? For example, parents who want to edit a child’s genome to dodge disease may also opt to modify appearance as a convenience because ‘we are there anyway.’ Our efforts should focus on curing disease and harm reduction, not on aesthetic manipulations to enable perceived society acceptance, as judged by parents or other potential stakeholders.

“Another question that is raised is at what point do the clinical procedures morph from cutting-edge therapy that does not require institutional review board (IRB) approval to true research, which does require rigorous IRB approval.”

David Goldstein is co-director of the USC Pacific Center for Health Policy and Ethics and is director of primary care at Keck Medical Center of USC. He is also vice chair of clinical affairs in the department of medicine at Keck Medicine of USC.

Contact: (323) 226-7592 or david.goldstein@med.usc.edu.

___________________________________________________

Huge potential to benefit and harm humans

“This technology is very powerful and has the potential to cure many genetic diseases. I expect that CRIPSR-Cas9-based therapies will be in clinical trials in the next few years. But before all that, we need to do a lot of research, including in early human embryos.

“We use the bacterial protein Cas9 to cut DNA; however, this protein may have unwanted functions in human cells. In some cases, DNA repair after a CRISPR-Cas9 cut is not perfect. The repaired DNA sequence could create a new protein that is harmful. Additionally, people think the chances of an off-target snip using CRISPR-Cas9 is extremely rare, but the probability of this happening is actually high. Just one off-target cut could cause big trouble.”

Qi-Long Ying is an associate professor of stem cell and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. He has been using CRISPR-Cas9 on embryonic stem cells since 2013. Ying has used CRISPR-Cas9 on heritable stem cells in mice and rats. His research goal is to sustain a cell’s ability to regenerate when needed.

Contact: (323) 442-3308 or qying@med.usc.edu

# # #

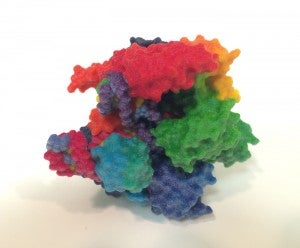

Image: 3-D printed Cas9 enzyme that snips a DNA sequence at a location identified by CRISPR. (Photo/NIH 3D Print Exchange, National Institutes of Health)