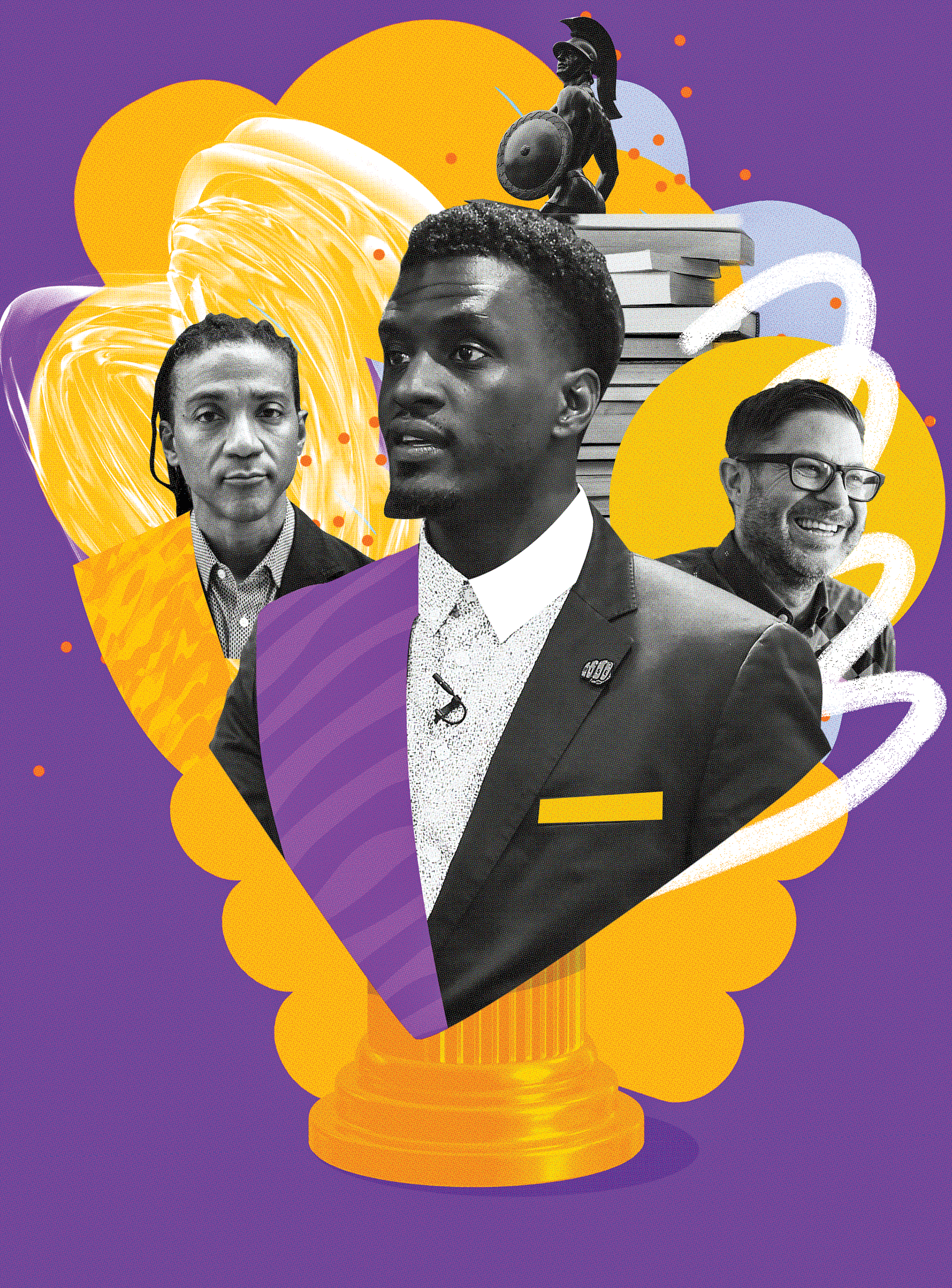

In every realm where hip-hop has made its mark on American culture, you’ll find USC faculty, students and alumni who have played leading roles in elevating and amplifying it on the national and international stage. (Illustrations/Temi Coker)

How USC helped propel hip-hop innovation

Some of the foremost innovators in hip-hop are part of the Trojan Family. USC artists and scholars look back on 50 years of the art form — and forward to its future evolution.

WHEN TODD BOYD FIRST ARRIVED AT USC in the fall of 1992, an explosive cultural transformation was underway. The former hip-hop emcee and newly minted professor at the USC School of Cinematic Arts had come to the university with the goal of shaping the nascent field of hip-hop studies.

The scars from the civil unrest that had erupted that spring in neighborhoods adjacent to USC following the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, a Black man, were still fresh.

“You could still see buildings that had been burnt and damaged,” Boyd says.

From those ashes, a formidable force of creativity was rising. Hip-hop artists in surrounding communities were funneling their pain into profound storytelling and shaping a new West Coast sound.

From that critical inflection point, Boyd helped connect USC to the thriving musical movement at its doorstep. He blazed the trail for USC scholars in every corner of the university who, like himself, study hip-hop’s historical underpinnings and cultural impact.

The creativity that burst forth from communities adjacent to USC now reverberates through arts education at the university. Today, USC’s arts schools, including the USC Kaufman School of Dance, the USC Thornton School of Music and the USC School of Cinematic Arts, are prominent incubators for innovation in hip-hop movement, music and visual culture, respectively. Andre Young — better known as Dr. Dre, one of West Coast hip-hop’s foremost artists and producers — became part of the Trojan Family when he and Interscope Records co-founder Jimmy Iovine launched their school for arts, technology and innovation, the USC Jimmy Iovine and Andre Young Academy, in 2013.

Hip-hop, which turned 50 last year, has followed a similar trajectory at USC as it has in American culture: from underdog to tour de force.

Started from the bottom, now we’re here

New York City, widely recognized as the birthplace of hip-hop, had been the music’s de facto epicenter since DJ Kool Herc started throwing parties in a rec room in the Bronx in August 1973. But in the late 1980s, groups like Compton-based N.W.A put South L.A. on the hip-hop map with their profane and powerful critiques of the racial politics of policing. By 1992, former N.W.A members Ice Cube and Dr. Dre had released smash albums with tracks explicitly responding to the civil unrest — and the national focus turned to USC’s backyard.

South L.A., Boyd says, became hip-hop’s “center of gravity.” Though USC was located at the nucleus of West Coast hip-hop, Boyd’s introduction of hip-hop into his curriculum was new to the university. While Howard University, a historically Black college, already offered a course on hip-hop at the time, Boyd says many in academia then regarded rap music as unworthy of study. It was considered a disposable fad at best and a threatening cultural force at worst.

Today, that script has been utterly flipped. Boyd (also known as the Notorious PhD) is now nationally recognized as one of the pioneers of hip-hop studies and a sought-after media commentator on the subject. His most recent book — Rapper’s Deluxe: How Hip Hop Made the World, published in February — chronicles the genre’s breathtaking rise over its 50-year history.

“Hip-hop is a cultural movement that has traveled this really interesting journey from being marginalized and ignored and dismissed and ridiculed, to helping to elect a president, influencing the way people speak and making connections to elite spaces, such as the world of contemporary art,” Boyd notes.

In every realm where hip-hop has made its mark on American culture — from music, dance and film to entrepreneurship and scholarship — you’ll find USC faculty, students and alumni who have played leading roles in elevating and amplifying it on the national and international stage.

How can we honor, uplift and celebrate Black culture, which is at the core of hip-hop?

— d. Sabela grimes

That’s the joint, and that’s the jam

“See, I went to USC. And got my college degree.” — Saweetie, “ICY GRL”

Saweetie (born Diamonté Harper) ’16, is among the power house hip-hop recording artists who chose to pursue their degrees at USC before their careers kicked into high gear. While Saweetie says she originally chose the university for the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism’s nationally ranked communications program, her “intention and motivation” changed once she fell in love with music.

“I wanted to go to USC to be in a primary market, where artists typically get discovered,” Saweetie says. “But I quickly learned that I needed to finish my degree before trying to pursue music full time because going to school full time is a beast of its own.”

While she’s proud of the success she’s experienced in her music and business ventures, she also uses her music to remind fans of the behind-the-scenes hard work and focus it took to get her degree.

“My songs don’t necessarily show my college girl side, so I wanted to shout out my education because that’s played a big role in my success,” Saweetie says. “It has helped me become a critical thinker and has also developed my emotional intelligence.”

Saweetie has followed in the footsteps of other notable Trojans who found success in hip-hop. In 1987, Young M.C. (Marvin Young ’89) was a junior in economics at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences when he signed the record deal that led to his 1989 album, Stone Cold Rhymin’, and its breakout single, “Bust a Move.”

Likewise, before he became a global R&B star, singer-songwriter Aloe Blacc (Egbert Nathaniel Dawkins III ’01) studied linguistics and psychology at USC Dornsife. The Renaissance and Trustee Scholar got his start in hip-hop as one half of the underground rap duo Emanon.

Though none of these superstars majored in music, USC Thornton is a magnet for up-and-coming hip-hop talent. Jason King, dean of USC Thornton, is a leading hip-hop scholar and music critic with interest in augmenting the school’s hip-hop curriculum. At New York University, where he previously served as chair of the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, King helped pioneer first-of-their-kind courses in the art of emceeing.

“I want to bring that same energy and that lens to USC Thornton in terms of training musicians in the context of excellence,” King says. “I would like for hip-hop to be taken as seriously as we take classical music or jazz music.”

He notes that USC Thornton has long offered a course in hip-hop music and culture, which is currently taught by musicologist Sean Nye, associate professor of practice. Many USC Thornton alumni have gone on to significant careers in hip-hop composition and music production. The school’s music industry major has been a launching pad for alumni working at top hip-hop record labels and in artist management, including Keaton Smith ’16 and Isa Klar ’23 of Top Dawg Entertainment, an independent label that has Grammy Award-winning artist SZA on its roster.

“But we don’t have a standalone hip-hop performance curriculum,” King says. “And most universities don’t. That’s one of the things that I’m really looking forward to helping build out and grow at the school.”

King believes that a background in hip-hop is important for all music students, regardless of their genre of interest. “Students studying any aspect of what it means to be a musician in the 21st century have to contend with hip-hop,” King adds, citing hip-hop’s commercial and critical importance.

USC Annenberg alum Heran Mamo ’19 recalls taking Nye’s hip-hop music and culture class during her time at USC and working on contemporary assignments such as having students write about the impact of the Black Panther movie soundtrack, which includes music scored by USC Thornton graduate Ludwig Göransson ’08. “It was so dope that I was able to take a whole class dedicated to a genre that I still report on,” Mamo says. “I learned not only about the origins of the genre, but also how it permeated popular culture.”

Today, Mamo covers hip-hop, R&B, Afro beats and popular culture as a Billboard reporter. She’s profiled some of the biggest artists dominating the airwaves, including cover stories featuring The Weeknd, Ice Spice and Burna Boy.

“What I really love about hip-hop especially is that it tells a story,” Mamo says. “Whether it’s racial injustice, police brutality, gentrification or crime, even the production [of the music] lends to the storytelling of what Black people are experiencing.”

Students studing any aspect of what it means to be a musician in the 21st century have to contend with hip-hop.

— Jason King

A communitywide cypher

At USC Kaufman, hip-hop is so foundational to the core curriculum that all Bachelor of Fine Arts students take hip-hop dance classes for four years — not just those focusing their studies on hip-hop. And the school’s minor in hip-hop, street and social dance forms is open to all undergraduates, regardless of dance experience.

“At USC Kaufman, we believe everyone has something to contribute to the evolution of hip-hop as an art form,” says Julia Ritter, dean of USC Kaufman.

Many of the hip-hop dance styles that students learn — breaking, locking, popping, house, whacking and krumping — were literally conceived on street corners. They morphed as they gained global popularity and were polished for consumption in dance studios far removed from the communities of color where they originated.

When USC Kaufman faculty were designing the hip-hop curriculum in 2014 — a year before the school opened its doors to students — their guiding question was, “How can we honor, uplift and celebrate Black culture, which is at the core of hip-hop?” says d. Sabela grimes, associate professor of practice.

grimes developed a system of movement called “Funkamental MediKinetics” that steeps students in the rich history of Black vernacular dance practices that preceded and influenced hip-hop. He and his colleagues also introduced opportunities for students to connect with the wellspring of creativity in the neighborhoods adjacent to USC.

The biennial Cypher Summit — which is organized by Tiffany Bong, assistant professor of practice, and celebrates women in hip-hop — is one of the many USC Kaufman events that gather community-based artists on campus. This year, for the first time, Bong collaborated on the event with USC Visions and Voices, a university wide arts and humanities initiative.

“Women have been innovators, leaders, organizers, pioneers and creatives of hip-hop dance culture since the beginning,” Bong notes. “It’s important to recognize that because most of the time they have been taken out of the story, or less featured or highlighted.”

Jakevis Thomason ’20 has worked with some of hip-hop’s top female recording artists. He recently toured with R&B/hip-hop musician Kali Uchis and contributed choreography to Beyoncé’s 2023 Renaissance tour — an opportunity that came about in a surprising way.

In 2021, Thomason choreographed a short dance film set to Beyoncé’s song “Black Parade.” After filming it at the top level of the USC Shrine Parking Structure, he posted it on YouTube — and it went viral. Beyoncé’s team later reached out to see if Thomason could teach his “Black Parade” choreography to her dancers so they could perform it on the tour.

“I freaked out,” Thomason says. “For her to see it was one thing, but for her to actually love it and want to use it … it was a dream come true.”

Thomason believes his training in hip-hop foundations has helped him stand out from the competitive pack in the commercial dance industry. “I feel like going back and understanding where things come from … can help you get to places you didn’t know were possible,” he says.

Bong says that USC Kaufman’s ability to ground students in local community practices and simultaneously propel them to global stages puts it at the forefront of new territory. “We are blessed with the opportunity and capability of being at the front lines every day to envision and shape where hip-hop and academia merge, and what can be birthed from it,” she says.

The revolution will be televised

The School of Cinematic Arts has produced countless visionaries in film, television and new media, but the early ’90s ushered in a new era for Black filmmaking and storytelling that realistically depicted Black American life in a way never seen before.

Among the Trojan visionaries who used the different elements of hip-hop to create powerful portrayals of the Black experience in South L.A. was L.A. native John Singleton ’90. As a newly minted USC alum, he wrote and directed the iconic 1991 film Boyz N the Hood, which was released mere months after the police beating of Rodney King. The film touched on many of the same themes that West Coast rappers such as N.W.A were shedding light on, including gang culture and police brutality, and its soundtrack featured leading hip-hop artists of the era, including 2 Live Crew, Too Short and Ice Cube — who also portrayed one of the film’s main characters.

“While not a hip-hop practitioner via music, in many ways hip-hop is a lens through which Singleton expressed himself, through visual culture and cinema,” says Taj Frazier, an associate professor of communication at USC Annenberg. Although some critics complained that the film glorified gang culture, it was overall a critical and financial success. The late Singleton would go on to direct many popular films on the realities of Black community life — featuring major hip-hop artists — including Poetic Justice and Baby Boy.

This is definitely an exciting phase in terms of hip-hop scholarship at USC.

— Taj Frazier

Rick Famuyiwa ’96 directed The Wood (1999), which stood out for its depiction of the Black middle class — a group the Inglewood native felt was not often portrayed amid stereotypes about “the hood.” Boyd collaborated as a writer and producer with his former student Famuyiwa: “It was meaningful to me because it had the mentoring aspect,” Boyd says. “I was trying to help create people who could work in the culture while doing that myself.” The Wood soundtrack is, of course, a who’s who of late-’90s hip-hop acts, including OutKast, DMX and Blackstreet.

Famuyiwa — who double majored in cinema/television production and critical studies at the School of Cinematic Arts — has continued to use hip-hop as a powerful backdrop as he’s centered the lives of the Black middle class of his community in subsequent popular films, including Brown Sugar and Dope.

Skin in the game

Learning to be a critical thinker at USC has helped Saweetie become not just a lauded entertainer with two Grammy Award nominations and the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding New Artist; her education also helped her develop entrepreneurial skills.

Saweetie started the Icy Baby Foundation to foster youth entrepreneurship, and has had partnerships with multiple brands including McDonald’s, MAC Cosmetics and Champion.

Among her achievements is one her music fans might not expect: a Distinguished Speaker Award from the USC Marshall School of Business. Since graduating from USC in 2016, Saweetie has returned as a guest lecturer at USC Marshall, where as a student she took “Business for Non-Majors,” a course taught by Albert Napoli, senior lecturer of clinical entrepreneurship. Napoli’s mentorship turned out to be pivotal to Saweetie’s leap into the music industry.

During Saweetie’s senior year, Napoli, who knew of her desire to become an artist and entrepreneur, spotted her at a career fair where she was meeting potential corporate employers. Napoli pulled her aside and said, “What are you doing here? This is not you. You’re not going to be happy.”

His guidance helped her decide to pursue music full force. “I am so grateful that, although I was going to such a prestigious university, my professor saw my hunger and passion to pursue something that you can’t get a degree for and supported that,” Saweetie says.

Returning to USC as a guest lecturer is one way she pays that mentorship forward. “It’s imperative that I go back and show the students that someone who looks like them was able to go out there and achieve their dreams,” she says. “I love going back to the students, and I love answering their questions, and I love serving them in any way that I can because I know that learning from someone who was once in their position can play a big part in someone’s journey.”

Saweetie’s successful business partnerships are an example of how prestige brands, many of which shunned hip-hop in its earlier days, now clamor to align themselves with the culture. Hip-hop credibility also gives artists a potent platform for their own business endeavors.

“Hip-hop has transformed marketing culture, has transformed brand culture,” USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun says. “It’s transformed the way we think about business and entrepreneurship.” Kun points to the success of Beats by Dre — the brand of headphones, earphones and speakers founded by Young and Iovine in 2006 — as one example of a company whose ascendancy is inextricable from hip-hop celebrity. Its success, in turn, laid the groundwork for the founding of the USC Iovine and Young Academy.

“We have this pioneering academy dedicated to startup culture, entrepreneurship and interdisciplinary technological thinking that is literally impossible without hip-hop,” Kun says. “[Beats by Dre’s] platform doesn’t happen without hip-hop, doesn’t happen without Dr. Dre, doesn’t happen without N.W.A. And it all goes back to South Los Angeles.”

Dropping knowledge

By the time Kun came to USC in 2005, universities around the country had already embraced hip-hop as a critical lens through which to view, analyze and dissect societal structures.

Kun — an L.A. native whose research interests include Mexican and Chicano hip-hop, which was rising in prominence in the late ’90s and early 2000s — frequently uses the crossfader as a metaphor for how cultural exchange and creation are at the heart of hip-hop’s power. A well-known cultural historian, author, curator and music critic, Kun has written and edited work on the history and politics of cultural connection, including Audiotopia: Music, Race and America.

“When we look at hip-hop at the 50-year mark, it is a seismic cultural shift,” Kun says. “With hip-hop culture, where the language of the world went from linear storytelling by a singular artist to collage culture, creating a montage to borrowing and appropriating little bits of culture and ideas from here and there, putting things together into a new narrative and creating a new mix — that’s all because of hip-hop.”

Hip-hop has followed a similar trajectory at USC as it has in American culture: from underdog to tour de force.

USC faculty incorporating hip-hop into their different disciplines embody this concept: “This is definitely an exciting phase in terms of hip-hop scholarship at USC,” says Frazier, who co-produced the 2019 documentary It’s Yours: A Story of Hip Hop and the Internet about how hip-hop artists have used the internet to revolutionize not only the music industry but also social and political movements. “We have so many unique scholars who teach about hip-hop, but even more broadly, who teach about Afro-Diasporic expression, vernacular and cultural forms and who bring in different approaches, backgrounds and philosophies in terms of how we teach about hip-hop, how we live it, how we experience it and how it shapes our own evolving consciousness.”

Frazier’s newest book, KAOS Theory: The Afrokosmic Ark of Ben Caldwell, explores the long-standing KAOS Network located in the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles and highlights how generations in South L.A. have passed down “the same kind of creative practice of experimentalism, innovation, not abiding by boundaries and rule breaking” that are the foundation of hip-hop.

He describes L.A. hip-hop as a manifestation of a community of villages with a shared history of colonialism, white supremacy and economic hardship that “bump and blur” against each other, passing down a kind of ancestral “education” that happens outside of the classroom, at kitchen tables, in cars, at bus stops, at reunions and other communal spaces. Iconic emblems of early L.A. hip-hop — including Soul Train, L.A. youth clubs, the pop-and-lock and breakdancing scene and lowrider car culture — embody this in how they drew in people from different races and walks of life.

That environment also reflects the exact kind of learning and communal scholarship that Frazier wants to inspire in his classes on campus. His courses on communication and culture focus on the poetic aspects of hip-hop, and how the genre’s different elements, including lyricism, dance and graffiti, enable listeners — especially those from the Black community — to cultivate a sense of self and awareness of the world.

Some USC faculty extend students’ worldly awareness by exploring hip-hop’s impact in a global context. Edwin Hill, a USC Dornsife associate professor of French and Italian and American studies and ethnicity, examines hip-hop as a means of cultural exchange. Through courses such as “Black Music and the Political Imagination” and his Maymester course “Hip-Hop Circles Around the World,” Hill’s pedagogy transports students through space and time to look at how forces such as colonialism have shaped the development of the genre globally.

But as important as the work of scholars has been to the evolution of the culture, hip-hop has always been a youth movement. Across USC, students themselves are bringing their evolving takes on hip-hop into the classroom and helping to shape the genre’s development. “One of the privileges and benefits of us getting to work with students that are in this season of life is that we get a chance to experience how they perceive and participate in a very contemporary understanding of hip-hop,” grimes says.

“In many ways, there’s a lot that we can learn from our students,” says Frazier, who notes that USC is a place where students are encouraged to bring their rich cultural histories to bear on their hip-hop studies. “Those arenas of culture, professional life and social life that matter to them — all that stuff that they’ve gotten from family and elders and those around them — they’re not told to leave that at home when they come here.”

Like hip-hop music itself, they’re “sampling” from the past to create the future.